So, a few of us have just submitted a letter contesting the Western Australia Government’s recent decision to delist dingoes as ‘fauna’ (I know — what the hell else could they be?). The letter was organised brilliantly by Dr Kylie Cairns (University of New South Wales), and she and the rest of the signatories have agreed to reproduce the letter in full here on ConservationBytes.com. If you feel so compelled, please voice your distaste of this decision officially by contacting the Minister (details below).

So, a few of us have just submitted a letter contesting the Western Australia Government’s recent decision to delist dingoes as ‘fauna’ (I know — what the hell else could they be?). The letter was organised brilliantly by Dr Kylie Cairns (University of New South Wales), and she and the rest of the signatories have agreed to reproduce the letter in full here on ConservationBytes.com. If you feel so compelled, please voice your distaste of this decision officially by contacting the Minister (details below).

Honourable Stephen Dawson MLC

Minister for Environment; Disability Services

Address: 12th Floor, Dumas House

2 Havelock Street, WEST PERTH WA 6005

([email protected])

cc: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions ([email protected])

cc: Brendan Dooley ([email protected])

Dear Minister,

The undersigned welcome the opportunity to comment on and recommend alteration of the proposed section (9)(2) order of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (BC Act) that changes the listing of the dingo from “fauna” to “non-fauna” in Western Australia. Removing the “fauna” status from dingoes has serious consequences for the management and conservation of this species and other native biota it benefits. Currently, dingoes are classed as A7, or fauna that requires a management policy. The proposed section (9)(2) order will move dingoes (as “non-fauna”) to the A5 class, meaning that dingoes must be (lethally) controlled and there will be no obligation for the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions to have an appropriate management policy (or approval).

Currently, under the Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 (WC Act) the dingo is considered “unprotected” fauna allowing management under a Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions management policy. A section (9)(2) order demoting dingoes to “non-fauna” will remove the need for Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions management policy and instead mandate the lethal control of dingoes throughout Western Australia.

As prominent researchers in top predator ecology, biology, cultural value and genetics, we emphasize the importance of dingoes within Australian, and particularly Western Australia’s ecosystems. Dingoes are indisputably native based on the legislative definition of “any animal present in Australia prior to 1400 AD” from the BC Act. Dingoes have been present in Australia for at least 5000 years. On the Australian mainland they are now the sole non-human land-based top predator. Their importance to the ecological health and resilience of Australian ecosystems cannot be overstated.

Over the past two decades, ecological research in Australian ecosystems and around the world has increasingly focused on the importance of the conservation of top predator populations for ecosystem health and the preservation of biodiversity. Diminishing top predator populations have often been associated with ecosystem instability and species decline. Australia now has a strong research focus upon top-predator conservation.

Australia is unusual in having only one medium-large sized terrestrial carnivore (15-20 kg). The protection of the ecological functions such a predator performs in Australia (ecosystem stability and resilience) is crucial. The extinction of a diverse suite of large carnivorous marsupials some thousands of years ago (and the more recent local and functional extinctions of quoll species across much of Australia) has already produced a drastic simplification of the structure of wildlife communities in Australia. The dingo is a keystone species that benefits small animals and plant communities by suppressing and changing the behaviours of mammalian herbivores and small-bodied predators (including foxes and cats). Their presence adds a stabilising influence and provides ecosystem resilience for endemic species and communities.

At a time of mounting ecosystem stress and species loss, the continued use of environmentally harmful lethal control on dingoes and environmentally functional “dingo hybrids” will likely harm confidence in the Western Australia State Government and the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions in the eyes of the general public and the scientific community.

The government appears to be basing its decision to un-list the dingo as “fauna” on a single, controversial publication in a specialist journal (Jackson et al. 2017). This publication does not present sufficient evidence or persuasive arguments to scientifically justify a taxonomic change from Canis dingo to Canis familiaris. Indeed, Jackson and collaborator’s arguments are based on a narrow interpretation of taxonomy based on the “biological species concept”. In fact, there is a peer-reviewed publication in press by a group of scientists disputing the opinions of Jackson et al. (2017) and demonstrating that the dingo is a separate and unique species of canid that is endemic to Australia. We can forward the article upon request.

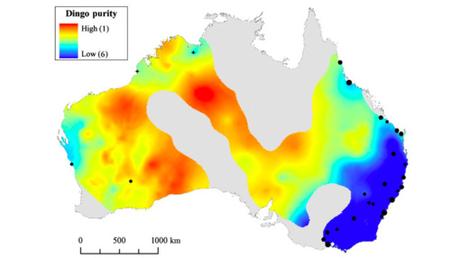

The other reason given for removing dingoes from the native fauna list appears to be a concern about dingo-domestic dog hybridisation. Extensive genetic testing of dingoes across Australia identified that 65% of wild dingoes in Western Australia carried no evidence of hybridisation (see below Figure 1). The dingo population in Western Australia is therefore one of the last remaining stable populations with high dingo ancestry. As dingoes and “dingo hybrids” have an imperative ecological role; it would be more appropriate for legislation to consider ecological function rather than strict genetic definitions, and arbitrary genetic “purity” thresholds. Strict genetic definitions will be difficult to monitor and manage in the wild and extensive regions over which dingoes occur.

- The negative ecological consequences of lethal control of dingoes will cause serious harm to the biodiversity, resilience and health of Western Australia’s ecosystems.

- The lethal control of dingoes will facilitate increases in mesopredator (cat and fox) and herbivore (kangaroos, wallabies and feral goats) populations that are currently managed as pests. This will in turn suppress threatened species populations.

- Concern about hybridisation is based on an ecologically unwarranted distinction between “pure” dingoes and ecologically functional “dingo hybrids”. Furthermore, WA has one of the largest remaining populations of “pure” dingoes.

- Changes to the taxonomy of dingoes from Canis dingo to Canis familiaris do not represent a widely accepted, scientifically supported consensus and are based on a narrow interpretation of the biological species concept. A concept that would consider species pairs such as humans and Neanderthals or wolves and coyotes, as the same species.

We strongly urge the Minister to reconsider his proposed section 9(2) order of the BC Act and instead suggest he should unambiguously endorse the dingo (irrespective of taxonomy) as “fauna” and direct the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions to develop a management strategy in Western Australia that would preserve and protect existing dingoes (including high content hybrids). It would be imprudent to make such an important decision based on a single publication presenting controversial and poorly supported opinions.

On the balance of scientific evidence, protection of dingoes should be enhanced rather than diminished. If the Minister wishes to maintain the “status quo” then he could maintain the dingo as “fauna” under the BC Act, but classify it as “managed fauna”, creating an exemption under section (149)(2)(b).

Signed:

- Dr Kylie Cairns, Centre for Ecosystem Science, University of New South Wales

- A/Prof Euan Ritchie, Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, Deakin University

- Rob Appleby, Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University

- Dr Bradley Smith, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University

- A/Prof Mathew Crowther, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Dr Melanie Fillios, School of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, University of New England

- Dr Arian Wallach, Centre for Compassionate Conservation, University of Technology Sydney

- Professor Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Matthew Flinders Fellow in Global Ecology, Flinders University

- Dr Justin W. Adams, Biomedical Discovery Institute, Monash University

- Associate Professor Mike Letnic, Centre for Ecosystem Science, University of New South Wales

- Dr Aaron Greenville, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Professor Chris Johnson, School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania

- Dr Tim Doherty, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University

- Dr William Parr, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney

- Dr Eloïse Déaux, Department of Comparative Cognition, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

- Lily van Eeden, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Dr Clare Archer-Lean, School of Communication and Creative Industries, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Damian Morrant

- A/Prof Dale Nimmo, School of Environmental Science, Charles Sturt University

- Dr Katherine Moseby, Centre for Ecosystem Science, University of New South Wales

- Dr Thomas Newsome, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney

- Professor Peter Savolainen, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden

- Dr Gabriel Conroy, GeneCology Research Centre, University of the Sunshine Coast

- Dr Brad Purcell, The Dingo Tracker – wildlife and ecological consulting

- Professor Chris Dickman, FAA, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney