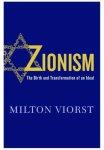

We are privileged to have with us today, renowned journalist, Milton Viorst. His new book: Zionism: The Birth and Transformation of an Ideal has been published this month from St. Martin's Press. Milton is a journalist who has covered the Middle East for three decades as a correspondent for The New Yorker and other publications. I feel particularly privileged to be Milton's literary agent for this new and important work of Jewish history.

We are privileged to have with us today, renowned journalist, Milton Viorst. His new book: Zionism: The Birth and Transformation of an Ideal has been published this month from St. Martin's Press. Milton is a journalist who has covered the Middle East for three decades as a correspondent for The New Yorker and other publications. I feel particularly privileged to be Milton's literary agent for this new and important work of Jewish history.

AR: Milton, thanks for agreeing to be interviewed on "Ask the Agent." There has been so much written on the subject of Zionism. Why do readers need another book about it?

AR: How have the aims of Zionism changed?

MV: The Zionist movement was founded at the end of the nineteenth century, when anti-Semitism was beginning to rage in Europe. Its founder, Theodor Herzl, was convinced the Jews needed a state, preferably in Palestine, in order to survive, and history has affirmed his judgment. But to establish a state, Jews had to overcome the fierce opposition of the local Arab inhabitants. In 1948, after a bitter Arab war, Israel was founded in most of historical Palestine. Then, in the Six-Day War of 1967, the Jews conquered the remaining territory in which the preponderance of Arabs lived, and they have since refused to withdraw from it. The oppressive military rule that Israel has exercised over the Palestinian Arabs has cost them much of the international sympathy from which their earlier aspirations once benefitted.

AR: Do most Zionists concur in the current policy?

MV: From its very beginning, Zionism has been sharply divided, not so much on the need for a state as on the nature of the state. Herzl himself warned of the obstacles created by merging the many and diverse societies in which Jews lived. In Herzl's time, the divisions were over how Jewish the Jewish state should be. Herzl was a sophisticated Westerner who envisaged a secular state, like most states of Europe. But Orthodox Jews, if they agreed to a state at all, could imagine only one that was ruled by Jewish law; while a majority of the Jews of czarist Russia, the most oppressed of Europe's Jews, insisted on a state that was not necessarily religious but was richly imbued with Jewish cultural values. In time these Jews prevailed.

AR: Was religion the only significant division?

MV: Not at all. The widest split in Zionism developed between Vladimir Jabotinsky's belief in the importance of the Jews using their own military force to obtain a state and David Ben-Gurion' s belief in the priority of building political and economic institutions that would serve as the backbone of the state. "Of all the necessities for national rebirth," Jabotinsky declared, "shooting is the most important. " Ben-Gurion, meanwhile, was busy organizing a political party based on social democracy, founding a national assembly and creating the Histadrut, a uniquely Zionist organization that was part labor union, part industrial corporation, and part social welfare society. It was Ben-Gurion's vision that led to a modern, prosperous Israel.

AR: Where did the Balfour Declaration fit in?

MV: In fighting World War I, Britain believed it had an interest in cultivating worldwide Jewry, and in 1917 it promised a homeland to the Jews in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire. At the same time, it promised not to violate the rights of the Arabs living in Palestine, creating a contradiction that was never really resolved.

AR: How did the Balfour Declaration play out after the war?

MV: Britain, with second thoughts, retreated on its pledges to the Jews. Jabotinsky, convinced that Ben-Gurion was wasting his time building institutions, argued for a militance in taking over Palestinian territory. The two men were bitter personal rivals for Zionist leadership, but their contrasting philosophies were also irreconcilable. In 1934 Jabotinsky and his followers, known as the Revisionists, seceded from the World Zionist Organization, which Herzl had formed to govern Zionism. To this day, the rift has not been healed.

AR: How did Jabotinsky's Revisionism and Ben-Gurion's mainstream Zionism handle their conflict during the struggle for independence?

MV: Jabotinsky died in 1940, but by then he had established his leadership over Betar, a militant youth organization closely tied to the right-wing regime in Poland. Betar gave Revisionism a fighting component, which it used to wage a guerrilla war against the British while they were still fighting the Nazis. Ben-Gurion stayed faithful to Britain until the Nazis surrendered, and his forces attacked only after Britain refused to allow survivors of the Holocaust and their children to enter Palestine. Even after Britain announced its withdrawal from Palestine in 1947 and Ben-Gurion prepared to declare Israel's independence, the rival Jewish forces could not compose their differences. Only after a brief but bloody civil war did the two camps, faced with attacks from their Arab neighbors, agree to fight together under the government's - that is, Ben-Gurion's- command.

AR: What did the Palestinians do to save their land?

MV: Not much. Convinced Jews had no rights to Palestine, and Britain had made it possible for them to be there, Palestinians insisted that both leave and allow them to found their own state. They initiated violence, in which blood was shed, but it was weak. More importantly, they created no governmental institutions, and organized no effective military forces. After the U.N. voted to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, they attacked the Jewish militias, but the competition was unequal. When Ben-Gurion declared independence, the armies of five Arab nations attacked the state, but the results were no more favorable to them. .

AR: Given Ben-Gurion's success as a state-builder, how did Jabotinsky's Revisionism wind up in power today?

MV: Many Israelis ask this question. Part of the explanation is that Ben-Gurion's creation, the Labor Party, having been deluded by its earlier triumphs into letting down its guard, was held to blame for Israel's near-defeat in the Yom Kippur war. But, in the long-term, Israeli politics changed because the Israeli electorate changed. A new generation of Sephardim- Jews from the Arab world- had now reached maturity, and was resentful that the Ben-Gurion camp had for too long ruled as if by a natural right inherited from Herzl. There also arose a militant religious movement , composed of observant young people who worked in the secular economy but were heir to the Religious Zionists of the Herzl era. After 1967, they embraced the doctrine that Palestine was holier even than the Torah, which inspired them to settle Arab land, though it often meant defying the state.

A decade later, Israeli voters transferred their long-standing loyalty from Ben-Gurion's camp to Menachem Begin, heir to Jabotinsky. Begin was not just the Revisionist rival; he was the non-Establishment alternative who took Israel on a more militant course, more defiant of world opinion. With only a few interruptions, it has since remained on that course. Benjamin Netanyahu, scion of a family long loyal to Jabotinsky, is today the leader of this course. Jabotinsky would probably approve of it, but the instability of Israeli life seems far removed from Herzl's Zionist vision of providing peace and security for the Jewish people.