The opening shots of Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris show the titular city from the perspective of a tourist, focusing on landmarks as tour groups walk and ride ferries around town. Occasionally, he spares brief glimpses of back alleys occupied by locals who know how to avoid the shuffling guests. Meanwhile, Allen lays French-flavored jazz, a Parisien take on American music, over such shots. He even literalizes the other part of the title by spreading the montage over the course of a day from sunrise to starless night, watching the blossom of the City of Light as dim interior lights grow into the full dazzle of Paris after dark. Despite the simplicity of Allen's static montage, he conveys a number of important ideas with the first moments: we do not see the Paris of those who live there but of tourists who visit it, and the sight of centuries-old landmarks looming over modern urban bustle shows the past mingling with the present.

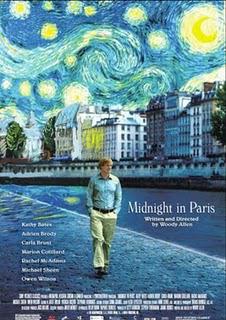

The opening shots of Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris show the titular city from the perspective of a tourist, focusing on landmarks as tour groups walk and ride ferries around town. Occasionally, he spares brief glimpses of back alleys occupied by locals who know how to avoid the shuffling guests. Meanwhile, Allen lays French-flavored jazz, a Parisien take on American music, over such shots. He even literalizes the other part of the title by spreading the montage over the course of a day from sunrise to starless night, watching the blossom of the City of Light as dim interior lights grow into the full dazzle of Paris after dark. Despite the simplicity of Allen's static montage, he conveys a number of important ideas with the first moments: we do not see the Paris of those who live there but of tourists who visit it, and the sight of centuries-old landmarks looming over modern urban bustle shows the past mingling with the present.That juxtaposition magnifies as Allen follows Gil (Owen Wilson), a successful hack screenwriter who looks to Paris for inspiration for his novel. Drunkenly wandering Paris one night while his fiancée (Rachel McAdams) dances with friends, Gil suddenly finds himself sucked into an old car after midnight, ending up amongst flappers, ex-pats and, most importantly, a host of legendary artists who dwelt in the city in the 1920s.

It's the dream of any creatively aspiring person, the chance to hang out with Hemingway or the Fitzgeralds, to get a book proofread by Gertrude Stein or judge a painting by Picasso. For Gil, whose book concerns a man running a nostalgia shop, the chance to walk around the past and interact with it is so wonderful only someone as capable of pure glee as Owen Wilson could pull it off.

Wilson gets a lot of flak, but I like him and can think of few other actors better suited to the role of Gil. Wilson has a voice that manages to convey simultaneous doe-eyed innocence and arrogant smarm, perfect for the insecure but ambitious writer. Gil walks around Paris, in both the modern day and the '20s, with a look of childlike wonder and joy on his face, but he's also cynical about his talents and bitterly antagonistic to Paul (Michael Sheen), Inez's uncomfortably close male friend and an officious fool who impresses others with his pontifications even after someone points out he's actually wrong about Rodin's mistress or the names of artists who designed and decorated Versailles.

Paul's insufferable lectures, all of which revolve around obvious tourist traps despite his image of being at one with French culture, sap all the fun from Paris, and even if Gil didn't get to walk around with the Lost Generation, one can hardly blame him for ducking away to the streets to avoid the man.

In a summer already marked by nostalgia in the form of Super 8 and, indirectly, the historical appropriations of X-Men: First Class and, soon, Captain America*, Allen's film is bizarrely attuned to the current mood. To be sure, it's undeniable he has his own fun with past literary and artistic figures. Ernest Hemingway (Corey Stoll) speaks the way the author's prose reads: brutal, aggressive, restless. Stoll looks like he dabbed absinthe on his neck as makeshift cologne, and when he screams, "WHO WANTS TO FIGHT?!" I can't imagine what clueless fool would take him up on it. Kathy Bates amusingly plays Gertrude Stein as a sort of Mother Goose for the artistic community in Paris, coaching the artists but also comforting them when mistresses leave.

After a time, I started registering the historical figure before the actor. Before Adrien Brody even said a word, before I even recognized him, I thought "There's Dali!" Tom Hiddleston and Alison Pill nail F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Hiddleston conveying the pain of his wife's tumult vying with his undying love for her and Pill communicating Zelda's schizophrenia long before it manifests. I kept waiting for the terrible impression to come along, the inevitable clunker of a performance that befalls all films where a cast has to deal with a huge number of real and significant figures. I kept waiting for the Condoleeza Rice from W. or the Churchill from The King's Speech. But Allen cast this movie impeccably: not only does everyone fit the part (almost uncannily so) but they all try to genuinely sound and act like some aspect of that person.

Yet the most catching character in the film is a mistress by the name of Adriana, forgotten by time but inspiring to a number of painters who changed that medium's landscape. From the moment the camera first settles on Marion Cotillard, she feels more like a muse than anyone to appear in a Woody Allen film, even Diane Keaton. That's not to say she's better, of course, but the camera almost physically reacts whenever she's on-screen. The frame seems to stop cold when she comes into it, frozen in first-sight love and intimidation of her beauty. It's like Allen is constantly surprised to run into her, conveying his trademark fluster through the lens as the camera tries to breathlessly apologize for stumbling upon her. And when she good-naturedly smiles at this flushed infatuation, the camera nearly swoons as if about to pass out. Cotillard could almost get away with saying nothing at all, but thank God she does, and her performance mingles so well with her presence that when the film begins to turn around her axis, the shift does not feel so seismic.

Adriana's own infatuation with a past time, La Belle Époque, brings out a more serious idea for Allen's whimsical tour of Paris past and present. He delights in roaming among artistic figures and even has fun with them—Gil pitches Luis Buñuel on The Exterminating Angel, only for the surrealist to be wholly unable to grasp why people couldn't leave a room—but he slowly brings out the idea that everyone pines for a Golden Age that is hardly considered such by those who lived in that time. One of the few insightful things Paul says, albeit condescendingly, is "Nostalgia is denial, denial of the painful present." Gil gradually comes to realize this, remarking to Adriana, "Maybe the present is a little unsatisfying because life is a little unsatisfying."

As such, Midnight in Paris ultimately critiques the wave of nostalgia floating through recent films, and even Allen's own The Purple Rose of Cairo. Allen comes to the conclusion that choosing to live in an idealized vision of someone else's existence is a hollow alternative to making one's own present into the best it can possibly be. There are suggestions of Allen identifying with Gil, who feels screenwriting is a lesser talent and yearns to be considered a literary talent, but Allen at last seems to be lightening up about his lot, and it shows in this film. Inez and her family are thinly written Republican caricatures, but Allen just wants an uncomplicated laugh, and who can afford to vacation in France these days except Hollywood liberals and conservative businessmen insulated against the economy? Gags of the past bleeding into present and vice-versa (would things have been different for Scott and Zelda if she'd been able to procure Valium?) offer visible comedy to go with the bouncing, witty script.

Nevertheless, it's the sober, positive conclusion the dour Allen comes to through the comedy and whimsy that makes Midnight in Paris truly deserving of the hype it's received. While this line may be tossed out with each new Allen feature, the film may rank someday among the director's finest. How strange it is that Allen, once one of those directors synonymous with a city, has achieved his greatest success in old age as a transient, his finest late-career work always forcing him out of his comfort zone. But then, at times he seems a better fit for Europe than even his dear Manhattan.

*Even, to an extent, The Tree of Life operates through nostalgia for a time period and setting that is not that of most of its audience.