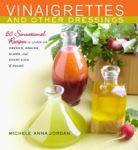

Today we are going to talk to Michele Anna Jordan about food writing. Michele is a James Beard Award winning author and food and wine writer. She is the author of 18 cookbooks. In 1989, she was voted Best Chef in the Sonoma County Art Awards. She lives and writes in Sonoma County where she pretty much has sewn up the title of “Sonoma food guru”. Her new book, Vinaigrettes and Other Dressings, was published this year by Harvard Common Press. Right now, it’s the best selling book on salad dressing in America.

Today we are going to talk to Michele Anna Jordan about food writing. Michele is a James Beard Award winning author and food and wine writer. She is the author of 18 cookbooks. In 1989, she was voted Best Chef in the Sonoma County Art Awards. She lives and writes in Sonoma County where she pretty much has sewn up the title of “Sonoma food guru”. Her new book, Vinaigrettes and Other Dressings, was published this year by Harvard Common Press. Right now, it’s the best selling book on salad dressing in America.

Andy: Michele, you’ve been writing cookbooks now for nearly 25 years. How has the market for these books changed during that time?

Michele: Readers don’t seem to have changed much. They still want what they did when my first book came out, which is to say good recipes with clear instructions accompanied by interesting stories and a context that is both broad and deep. Readers like context–not just culinary, but also geographic, historical, emotional.

But getting a book into a reader’s hands has changed in big ways. Advances are a fraction of what they were a decade or so ago. More of the marketing and promotion work is put onto the author. Some publishers do nothing or next to nothing to promote the book once it’s published. Publishers expect the author to provide photographs and other materials to the publisher free of charge. The kind of high quality food photographs you see in cookbooks can be very expensive to produce. With my first book, I was offered $2000 for testing expenses. That never happens now.

Andy: Has anything gotten easier?

Michele: Yes. I no longer print out a 500-page manuscript and send it off by FedEx. Nearly everything, except for final galleys, is done by email. Of course, that means no more “It’s in the mail” excuses to buy time, either. With my most recent book, nearly all the editing was done digitally. Quality photographs are, for the most part, much easier to produce these days too. All this speeds up the process and gets the book to the marketplace more quickly than in the past.

Andy: It seems like celebrity chefs are a bigger part of the food world than ever. How does The Food Network and food TV play into this? How is it manifested in the book publishing world?

Michele: Chefs and cooks were once simply physical laborers. Early cookbooks were written by doctors and then Fanny Farmer and the Domestic Scientists came along at the end of the nineteenth century and began to codify home cooking. This codification also lead to over-manipulation of foods and attempts to deny both appetite and the pleasure we take in eating. This had a pretty devastating impact on the American palate.

Andy: So when did all this start to change?

Michele: Stay with me here a minute, okay?

Fast forward to the Gourmet Revolution of the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the back-to-the-earth movement coincided with increased European travel and a re-emergence of pleasure as a pursuit. Alice Waters, herself not a chef but an inspired restaurateur, rode this wave to fame and fortune. In her wake came all that we see today: Restaurants as havens of the best food, chefs as elevated celebrities, home cooks — by definition inferior. Vanity cookbooks–coffee-table books that tell a chef’s story or a restaurant’s story and offer recipes put together by a kitchen staff of a dozen or more sous chefs — became a huge industry. This all received an enormous boost when The Food Network finally took off.

Andy: So how did putting it all on TV change things?

Michele: It’s made cooking a spectator sport, passive entertainment for a huge portion of the population. It’s left us feeling disempowered, in the sense that the Food Network makes us believe that it requires some sort of magical talent to make great food. I find this sad, since the real skill of a professional chef is management and consistency, the ability to put out plate after plate of reliable food day after day. You don’t need this skill to be a fabulous home cook. You just need to make fabulous food.

Now, back to the codification and over-manipulation of food. Thomas Keller of The French Laundry is often heralded as the best chef in America or even the world. I use him as an example because he’s probably the best known of his ilk. But if you look at his food, it’s over-manipulated to the degree that it is more of an intellectual exercise than a sensual pleasure. He and others like him have brought cooking back to where it was for the Domestic Scientists, who took great pleasure in creating such things as “all white meals,” in which everything was cut quite precisely and cloaked in white sauce, frosting or such so as to disguise it entirely. Pleasure and its handmaiden, appetite, were the bane of their existence. This newest version of their aversion to appetite has had a pretty devastating effect on the American palate.

Anyone interested in this part of our culinary history must read Perfection Salad by Laura Shapiro.

Andy: Michele, explain that a little more. I went to the French Laundry, and the food was delicious. Are you saying it doesn’t taste good?

Michele: I feel like Thomas Hardy after the publication of Jude the Obscure, when he said he’d be a fool to stand up and be shot (he was referring to his decision not to write any more novels). but here I go, I’m standing up.

In all honesty, Keller’s food doesn’t always taste good. When I was there about a year and a half ago, a couple of things were good but not great, some things were mediocre and a few things were not good at all–but most things looked lovely, in a very symmetrical, constructed and often clever way. And I found certain elements offensive. For example, a tower of eight white plates and saucers elevated an espresso cup full of what was said to be carrot soup. Eight plates! All I could do was think about the poor dishwashers and the water they’d need. And the soup? It was hot carrot juice with a leaf of tarragon. I love purity of flavors and the showcasing of single foods grown and harvested perfectly but hot carrot juice is a bit disgusting.

Andy: Yuck!

Michele: Most presentations were like this, cerebral, ostentatious, pretentious and, in the end, not about the food.

What most offended me were the four dessert courses, each one with several highly manipulated elements. I felt infantilized and, really, just wanted another lamb chop or some such, since there really wasn’t all that much on the savory side. I was embarrassed, too, because neither I nor my companion wanted all those sweets–they were cloying and a bit candy-shoppish. We just pushed them around on our plates so our waiter would think we’d eaten.

And the bill! It was $668 for lunch for two, which included just two glasses of sparkling wine and one glass of pinot noir. Two people could fly to Hawaii and back for the cost of one mediocre, forgettable lunch.

Andy: Boy, I hope your partner grabbed the check! Ok, let’s say that I’m getting started in cooking and I want to have one book that tells me all I need to know. It used to be The Joy of Cooking. Does that book still reign supreme? Or is it just a well established name brand? What are some good alternatives?

Michele: I think the 1974 edition of The Joy of Cooking remains an invaluable resource. The 1964 edition is excellent, too. The 1997 edition, not so much. But nothing has replaced it. Some have tried but none have succeeded, not so far.

Andy: That’s very interesting. How are the editions different? Have they changed because of food trends?

Michele: Yes, the 1997 edition was too trendy. A group of well-known chefs did the revisions and there was more focus on professional techniques, flavors and ingredients than previous editions, which have so much down-to-earth kitchen wisdom. As soon as I looked through it, I realized it was not going to become a classic. And it hasn’t.

Andy: So now I have my one standard book. And I want to build a modest cookbook library. What are the next 10 titles that I should buy for my kitchen shelf (after I purchase Vinaigrettes, of course)?

Michele: This is a personal question that depends on your food preferences, how much time you like to spend shopping and cooking, etc. I read cookbooks for inspiration, and I recommend them for this purpose too. So this is a very personal list that represents a wide range of cuisines. The first book is one I always recommend. Sadly, it is out of print, though you can find it fairly easily on line. It is brilliant but overlooked and underrated.

Unplugged Kitchen by Viana LaPlace

Fish Forever by Paul Johnson

Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone by Deborah Madison

The Art of Simple Food by Alice Waters

The Classic Italian Cookbook by Marcella Hazan

The Italian Baker by Carol Field

The Art of Mexican Cooking by Diana Kennedy

Bistro Cooking by Patricia Wells

Arabesque by Claudia Roden

The Original Thai Cookbook by Jennifer Brennan

Andy: You can get hundreds of thousands of free recipes on line. Just look at Epicurious. Why would anyone need to buy a cookbook any more?

Michele: When it comes to free on-line recipes, it’s a jungle. So watch out for those pretty but poisonous plants. I frequently peruse the major recipe web sites to see what’s there and I’m appalled by what I find: poorly written and untested recipes predominate. A lot of them absolutely will not work. There is no consistency when it comes to seasonality or quality. Randomness rules. Sure, you might find a recipe you like. But there will be no context, no relationship. Nothing is vetted; there’s no central voice.

A good cookbook has been vetted on many levels. Recipes are tested. There’s a voice, a point of view, at the center of it all. There’s context and, in the best of them, there is depth. A good cookbook is like a friend who joins you in the kitchen. It’s a relationship, not a one-night stand.

Andy: When I think of regions that are important in the food world in California, the places that come to mind are Napa and maybe Berkeley. Last time we talked, you said something surprising. You believed Sonoma County is much more important now than either of those places. Care to elaborate?

Michele: I could write books on this topic. Oh, wait, I have! Sonoma County has always been much more important when it comes to food than either Napa or Berkeley. Berkeley has plenty of claim to fame, of course, and launched the Gourmet Ghetto and the food revolution and gave us John Harris, Alice Waters, Les Blank, Peet’s Coffee, Acme Bread, Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant and so much more. It spread the gospel. But look at early Chez Panisse menus: They are filled with foods and wines of Sonoma County.

Napa has a singular focus, wine. It is a long inland valley with temperatures that rise as you head north. It was easy to spread the gospel of Napa because there was a single story, which Robert Mondavi told exquisitely well. The walnut and cherry orchards and other farms and ranches mostly disappeared as viticulture eclipsed everything. There are plenty of high-end restaurants with world-wide reputations in Napa, which makes sense, given the wine business. But this is about dining, not about cooking or farming or ranching. Napa produces some food, yes, but it must reach beyond its borders for most of its raw materials. The first place they reach out to is Sonoma. Attend any farmers market in Napa County and you see dozens of vendors from Sonoma County.

Sonoma County has five major valleys, with dozens of microclimates within these valleys. It has a seacoast. Our history of farming and ranching extends back to the 1800s, when an olive oil industry thrived here and Luther Burbank called it the chosen spot of the entire planet, as far as nature is concerned. We have some of the country’s finest dairies and the cleanest milk in America. We have extraordinary cheese makers and yogurt producers. Pastured eggs and poultry, the best lamb in the US, glorious duck, succulent grass-fed beef, delicious pork and goat, all come from our ranches and farms. We were pioneers in mesclun, the salad mix that is now everywhere. In the early 1980s, high-end restaurants from Honolulu to New York City had Sonoma County mesclun on their menus. Several local foods–the Gravenstein apple, the Bodega Red Potato, the Crane Melon and Dry Jack Cheese among them–have been taken onto the “Ark of Taste” by Slow Food.

There is a long history of home cooking here, too, with a patchwork of influences that include Portuguese, French, Italian, Swiss and German immigrants. More recently, Asian immigrants have had an impact on the region, too, especially on our agriculture.

According to several recent polls, Sonoma County is the top destination for wine travel, for wine and food travel and for food tourism. Healdsburg has been named one of the ten best small towns in America.

Frankly, I thought this would happen sooner than it has. My first book about Sonoma County food came out in 1990 and my second, a revised and expanded edition, came out in 2000. Both were ahead of the curve by several years. But now, Sonoma County is on the national and international stage, as it should be. It’s both a satisfying and a worrying development. We need to protect and preserve what we have, one of the finest agricultural environments in the world.