Till “Love-Death” Do Us Part

Wagnerian Love Couple: Ludwig & Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld as Tristan and Isolde (1865)

Wagnerian Love Couple: Ludwig & Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld as Tristan and Isolde (1865)

Tristan und Isolde, Wagner’s singular and most personal creation, derived from the 12th-century myth of Tristram and Iseult: he, a brash Cornish knight; she, an irate Celtic (or Irish) princess. In most sources cited, the story was undeniably linked to the love affair between Sir Lancelot, a knight of the fabled Round Table, and Queen Guinevere from the old Arthurian legends.

In a comparable vein, one of Wagner’s earliest successes, the opera Der fliegende Holländer (known widely as The Flying Dutchman), had at its root a basis in fact as well as in legend. A Dutch ship’s captain by the name of Hendrick Van der Decken (an alias for Barend Fockesz, or Bernard Fokke in some sources), challenged the devil himself by swearing to sail round the Cape of Good Hope, come hell or high water. The devil took him at his word and condemned the captain and his crew to eternity on the high seas.

In later versions, the Dutchman would be allowed ashore once every seven years to seek redemption for his sins through the love of a true and faithful woman. This basic theme, which Wagner had first introduced in his 1843 adaptation of the Dutchman’s tale, would reverberate throughout his personal and professional life. Even in his last stage work, the “consecrated festival play” Parsifal (1882), Wagner had the main character tempted to sin by Kundry in her guise as a voluptuous whore — the farthest thing from a true and faithful woman imaginable, albeit a ploy to fulfill the necessities of the plot.

In the characters of Tristan and Isolde, however, Wagner was dealing with the philosophical and psychological components of unquenchable passion; of an ardor that knows no earthly bounds, one that transcends the mortal confines of this life and into the nebulous realm of never-ending night, a synonym for death.

We could spend hundreds of untold hours and chapters (and many authors have done exactly that) in expounding further upon these insights. For the time being, though, let me deal with a few matters at hand.

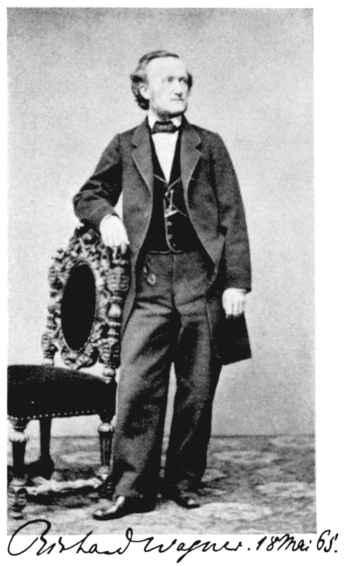

One of these, the theme of the self-sacrificing woman giving herself wholly to save a lost soul, could only have sprung from the self-absorbed intellect of Richard Wagner. Whose soul was it that needed to be saved? Whose whims were needed to be catered to? Why, Wagner’s, of course! Let’s not be fooled by the fluff: no matter how he hard he tried to cover his tracks (and he tried hardly at all, in many instances), the only person Wagner cared for above all others was himself.

Was this necessarily a bad thing? Oh, absolutely it was! Did Wagner create meaningful works in the process? You’re damned right he did! What difference did it make if he constantly interjected himself into the plot lines of his compositions, or borrowed from himself (as Rossini had so often done) to make a musical-dramatic point?

Reading between the lines, the listener can picture Wagner as Tannhäuser, a man torn between the love of a “good woman” Elisabeth versus that of the goddess Venus. In Lohengrin, he’s the knight in shining armor, come to rescue the damsel in distress Elsa from a false accusation of murder. In the Ring cycle, he’s the head god Wotan, lording it over (and loving) whomever he chooses. In Die Walküre, he’s Siegmund, free to love the wife of another man, even if the wife happened to be his twin sister! He’s also Siegfried, the original nature boy, blessed with untold optimism, knowing no fear, invincible to his enemies — except when his back is turned. And lastly, he’s Walther von Stolzing in Die Meistersinger, a minstrel in the making, seeking entry into the Master’s Guild, a high-born agitator with his own revolutionary mode of writing.

Need we say more? Well, if you insist: Wagner is the Dutchman personified — mysterious, gloomy, accursed, and tormented. His seven-year intervals extended throughout and beyond his career. Reading about his exploits, I am constantly amazed that Wagner’s very existence was fueled by extraordinary purpose, of an absolute and unbridled faith in his abilities, no matter the consequences to himself or to those around him.

Naturally, one can take these sorts of comparisons a tad too far. But there is a fascinating side note to all of this: the artists who created the roles of Tristan and Isolde — the husband and wife team of Ludwig and Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld — epitomized the central romance inherent in Wagner’s opus.

Tall, stout, and portly, Joseph Albert Ludwig was an immensely talented, 29-year-old Munich-born tenor; soprano Malvina Garrigues, a decade older, was a Danish-born, Portuguese descendant. The two singers had separate operatic careers, but eventually met in the city of Karlsruhe, in southwest Germany.

While at the Karlsruhe Opera, they appeared together in several works (according to Wikipedia, in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots among them). Ludwig’s official debut in Karlsruhe occurred in 1858, while Malvina had previously sung there in 1854. The couple hit it off from the start, and in 1860 they tied the knot.

A Cry from the Heart

The story goes that the Schnorr von Carolsfelds so impressed the young King Ludwig II of Bavaria that he recommended them to Herr Wagner. The composer eventually met the couple in Wiesbaden, around 1862, a good three years before the first performance of Tristan und Isolde took place at the Court and National Theater in Munich.

The evening of June 10, 1865 would go down in musical history as a major conquest if not a triumph for all concerned. Not one year earlier, Wagner was at the lowest point in his troubled life, until he was introduced to the newly crowned Ludwig II, who set him up at a villa near the king’s lakeside residence.

In April 1865, Wagner’s illicit affair with Cosima von Bülow culminated in the birth of their daughter Isolde, named after the heroine of his opera. As for the June 10 premiere of Tristan, it was prefaced by months of continuous rehearsals and unforeseen reversals of fortune, to include the cancellation of the original May 15 date due to Malvina’s loss of her voice (she had “caught a chill in her bath,” as noted in William Berger’s Wagner Without Fear).

Finally, the curtain went up before a gala audience that witnessed the start of a legend of its own making. Ludwig and Malvina were the perfect pair, billing and cooing like two elephants in heat (this is unfair to Malvina, who was much slimmer by many kilos than her robust mate). The conductor was none other than Cosima’s legal partner, Hans von Bülow who, we are informed, led a masterful reading of Wagner’s complicated score. Although the press and public remained befuddled by the experience, most critics agreed they had been privy to something out of the ordinary: they felt transported to another time, to another place, via Wagner’s music.

Tristan was given three more performances (one by royal decree), where it started to pick up a head of steam. Afterwards, tenor Ludwig moved on to Dresden to sing Erik in The Flying Dutchman. A few days before July 21, Herr Schnorr von Carolsfeld complained of chills. This was followed by what was termed “rheumatic complications,” which may have been the result of a sudden fever whereby he suffered either a debilitating stroke or a lethal heart attack. That, and the fact that he was severely overweight, led to Ludwig’s premature death only 19 days after his 29th birthday.

It was rumored that his last words were “Tristan!” Some sources insist that he cried out the composer’s name instead. Given that he passed away after singing the strenuous role over several back-to-back performances, the rumor has long persisted that the part had ultimately done him in.

As for his bereaved spouse, Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld fell into despair and depression. She went on to quit the opera, never to perform on stage. She also never remarried, having died a widow in Karlsruhe, in 1904, at age 78.

In many people’s view, Ludwig and Malvina were the real-life Tristan and Isolde. Their love transcended the boundaries of the theaters in which they both performed in. As far as we know, and unlike their titular counterparts, the Schnorr von Carolsfelds were true to each other in all things matrimonial. They were the embodiment of the vow, “In sickness and in health, for richer or for poorer, till death do you part.” In their case, however, in light of the roles they played on stage, we can make an exception: Till Liebestod (or “love-death”) did they part.

(End of Part Three)

To be continued….

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements