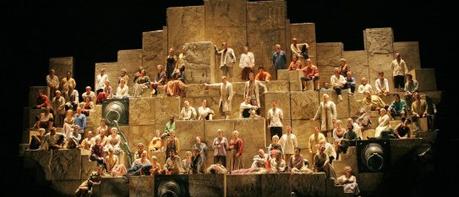

Set for Verdi’s Nabucco at the Met (Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera)

Set for Verdi’s Nabucco at the Met (Photo: Marty Sohl / Met Opera)Now, Where Were We?

Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio and Verdi’s Nabucco. The time interval between these two radically diverse works was half a century. Mozart composed his three-act comic masterpiece (a Singspiel, or opera with spoke passages) in 1782, while Verdi completed work on the four-act drama Nabucco in 1842.

Not only were these two operas as different from one another as the proverbial day from night, but the lifestyles of their respective creators were equally as far apart. Despite the disparities, Verdi and Mozart were students of politics. All throughout his short life Mozart struggled with his inability to be taken seriously as an artist. Perhaps it had to do with his more playful, carefree nature. On the other hand, Verdi was dead serious from the start.

Who could have foreseen that these two great musical minds might have shared a commonality of thought: the humanist and eternal optimist Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart versus the darkly pessimistic genius of Giuseppe Verdi?

They both experienced extraordinary success as well as the deepest sorrow and tragedy. In Verdi’s case, as recognition in the Italian opera world was within his grasp, within a span of a few short years Verdi lost his entire family, comprised of two small children (a girl and a boy) and his raven-haired wife, Margherita. In his own words, Verdi insisted they had perished in a matter of months. Not so, although biographers have often cited his version of the story for its dramatic impact.

We tend to forget in our so-called “enlightened” times that early childhood deaths were a common occurrence in centuries past. This was why families, whether they had the means at their disposal or not, produced large broods of siblings. In fact, it is not generally known that Mozart had produced children of his own — by some counts, as many as six from his wife, Constanze Weber (some say no more than two). His papa, Leopold, beside Wolfgang and older sister Maria Anna (nicknamed “Nannerl” by Wolfie himself), fathered an additional handful of children, all of whom died young.

In contrast, Verdi sired no more offspring — and by that, we mean legitimate ones. His long-time, live-in lover, the former singer Giuseppina Strepponi, may have resulted in at least one illegitimate daughter (given up for adoption). Much later in life, Verdi was taken with a seven-year-old cousin of his, Filomena, whom the composer rechristened “Maria” and officially adopted as his own.

As far as politics was concerned, Mozart, during the time that he lived and worked in Salzburg, then later in Vienna, may have floundered on many occasions but continued to navigate the ever-changing headwinds as best he could. Certainly, he ran into the censors; and finances (or the lack of them) were a constant, pressing issue.

It was Mozart’s fondness for living high on the hog, his immaturity regarding money matters and inability to maintain a steady source of income that historians felt contributed to his dire financial condition. They may also have precipitated his decline into a premature death at the age of 35.

With Verdi, who was born to modest means (even though he felt that his family was poor) and blessed with life-long robust health, musical ability, along with shrewdness and thrift and a peasant’s appreciation for cultivating the land, made the Master of Busseto a very wealthy man.

Lucky in life, lucky in art, but that would all come later. In 1842, however, Verdi had reached rock bottom. He was commissioned by a fellow called Merelli, the impresario of La Scala, Milan, to write an opera based on the Old Testament monarch King Nebuchadnezzar, or Nabucco for short, and the Babylonian captivity of the Hebrews.

The legend goes that after the failure of his 1840 romantic light-comedy Un Giorno di Regno (“King for a Day”), coming so soon after his family’s passing, Verdi had given up the notion of composing as a stable occupation. Running into the impresario on Milan’s streets, Verdi, in the direst of depressions, reluctantly agreed to take up the challenge of a new opera. He had no choice, when you come right down to it: Merelli had his signed contract, so Verdi was honor bound, as well as legally bound, to provide an opera for La Scala at the height of its season.

Ever the dramatist, Verdi would later claim that he came back to his hotel room and threw the libretto onto his bed (or table, in some versions). Miraculously, the pages opened up to the words “Va pensiero, sull’ali dorate” (“Go, thought, on golden wings”), the cry of the Hebrew slaves yearning for their homeland. Duly inspired by the lyrics (set down by the librettist and poet, Temistocle Solera, a hell of personality in his own right), Verdi was overcome with emotion — but not enough to do justice at that point.

He tried to return the libretto, but Merelli would have none of it. Thrusting it back into the composer’s coat pocket, Merelli left Verdi to his own devices. This is a wonderful story, which, in Mary Jane Phillips-Matz’s scrupulously researched biography, does not disprove outright, but only questions as to its veracity. The fact remains that Verdi went on to complete the music, and Nabucco, as the opera came to be called, became a tremendous hit.

Verdi’s future lover and spouse, Strepponi, was cast as Abigaille, Nebuchadnezzar’s adopted child. Their father-daughter relationship, fraught with nervous tension and high-flying vocal pyrotechnics, provides a powerful contrast to the prayer-full Zechariah’s messianic musings.

But the crux of the work, and the raison d’être for its continued success, is the emotionally compelling chorus “Va pensiero.” The Robert Shaw Chorale recorded the definitive version of this piece for RCA Red Seal’s Living Stereo label, but any opera company worth its weight in seasonal subscriptions can deliver the goods.

What You Hear is What You Get

The Metropolitan Opera Chorus, led by its choir master Donald Palumbo, is one of the finest such ensembles on the planet. It got a stirring ovation at the premiere of Nabucco earlier in the season, with the “Va pensiero” chorus itself getting a deserved encore. No such luck at the January 7, 2017 Saturday matinee performance, which starred Plácido Domingo in the title role, soprano Liudmyla Monastyrska as the fiery Abigaille, and bass Dmitry Belosselskiy as Zaccaria (the spelling of these Slavic names will be the death of me!).

James Levine conducted the Met Opera Orchestra in this Elijah Moshinsky production, with massive sets by John Napier and appropriately classical costumes by Andreanne Neofitou.

No need to tell readers that the opera Nabucco is a travesty of ancient history. It makes nonsense out of the plot, and even imposes on the title character an uncharacteristic religious conversion! My favorite recording of the work is the first note-complete stereo version on Decca/London, with the great Tito Gobbi as Nabucco, and Elena Souliotis (in her finest Maria Callas incarnation) as his daughter. The two make an impressive team, along with Lamberto Gardelli’s expert leadership on the podium. If only Carlo Cava as Zaccaria were of equal worth …

As for the Met’s radio broadcast, I’m a firm believer that Domingo has ventured far beyond his normal capacity as a tenor into the baritone realm. It may be too late for him to ever go back, but I must say that here, his dramatic instincts were far better served than his vocal ones. By all reports, Domingo managed to dominate the stage whenever he was on — even if his resources have now winnowed down to an audible but decidedly low-level caliber.

As Abigaille, Monastyrska made some imposing noises, although her coloratura needed steadiness and control. Notes poured out of her with a galvanizing wallop, but the dramatic purpose behind them was lacking. A mighty sound indeed! With careful nurturing, she may turn out to be a singer worth hearing. For now, let’s say that Liudmyla is getting a thorough workout at the Met’s dramatic bel canto wing. She knows how to husband her resources, which is a better verdict than some of her predecessors received, including the aforementioned Souliotis, whose career fizzled out much too soon, and that of Italian diva Anita Cerquetti in the late 1950s to early 1960s.

The January 14 Saturday broadcast of Puccini’s popular perennial La Bohème, in the by-now-classic Zeffirelli production (with costumes by Peter J. Hall), brought out an essentially youthful cast of aspirants, which is as it should be.

Among the raw talents on display were baritone Alessio Arduini as a tremulous Marcello, tenor Michael Fabiano as an especially ardent Rodolfo, bass Christian Van Horn as Colline, baritone Alexey Lavrov as Schaunard, veteran basso Paul Plishka in the dual role of the tipsy landlord Benoit and cuckolded old geezer Alcindoro, the lovely Ailyn Pérez as Mimì, and brassy Susanna Phillips letting it all hang out as the noisy Musetta. The opera was conducted by Carlo Rizzi, who knows this verismo terrain about as well as anyone.

While most of the above artists tread lightly over their parts, I was immediately impressed by tenor Fabiano’s bright, lava-like outpourings as the poet Rodolfo. Incidentally, I was struck by his similarity in timbre to the late Franco Corelli. Mind you, this comparison to a primo tenore of the Met’s unrivaled Golden Age was more than just mere coincidence.

I do not attribute Corelli’s incredible lung power and unmatched ability to coax high notes out at his will and pleasure (when Franco was able to exercise control over his output) to anything that Fabiano displayed. No, it was just that Fabiano’s basic sound, the way he shaped the poet’s words and phrases — most markedly, how he caressed the vocal line by either lengthening it or bending it to his particular purpose — smacked of a growth in artistry I had not expected of him.

The climax on high C of “Che gelida manina” (“How cold your tiny hand is”), the true litmus test for any aspiring lead, was well handled. I sensed only slight discomfiture in his handling of it. He ended his narrative softly, running out of breath at the phrase “Vi piaccia dir.”

Ailyn Pérez was an appropriately vulnerable Mimì, without erasing the memory of such past luminaries as Montserrat Caballé, Mirella Freni, Renata Scotto, and Ileana Cotrubas. Soprano Phillips cleared the stage of rivals as a thoroughly bombastic, self-absorbed Musetta in Acts II and III. God help the fellow who got in her way! She powered down noticeably for Act IV, where Musetta displayed her sensitivity for and empathy with Mimì’s situation.

Wherefore Art Thou, Roméo?

About the best one can say for these January broadcasts was that here, in little old Raleigh, we had good weather for most of the month. That was not the case in New York, my old Met stomping ground. Because of this, I had mixed feelings about the January 21, 2017 transmission of Charles Gounod’s romantic opus, the five-act French opera Roméo et Juliette, based on Shakespeare’s tragic play.

This new production, the handiwork of director Bartlett Sher and set designer Michael Yeargan, with costumes by Catherine Zuber, lighting by Jennifer Tipton, choreographer Chase Brock and fight director B.H. Barry, brought back fond memories of a relic from the Old Met’s days on Broadway and 33rd Street. During those halcyon times the company staged this piece with Bidu Sayão and Jussi Bjoerling in the leads. At Lincoln Center in the late 1960s, a production that starred Mirella Freni and Franco Corelli brought out these respective singers’ fans en masse (perhaps all they wanted to see were Franco’s manly thighs in hip-hugging tights).

Getting more than they bargained for, followers of the contemporary teaming of German soprano Diana Damrau as Juliette with Italian tenor Vittorio Grigolo were regaled with his (as per the Met’s sure-fire ad campaign, he was supposed to be shirtless) appearance as an intensely involving Roméo. Grigolo was the hit of the season, and not just for his hunky Roméo, with high notes blazing, sword flashing, and crooning and carrying on to his fans’ delight; he made an especially memorable Nemorino in Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’Amore, as well as a brooding, Byronesque Werther in Massenet’s eponymously titled opera.

With a voice to match his strikingly good looks, this was French opera in the raw. Could Signor Grigolo be the next generation’s embodiment of Corelli? Already he’s been tapped to replace the smoldering Jonas Kaufmann as Cavaradossi in next season’s new production of Puccini’s Tosca. Wait till you hear Vittorio’s second act cry of “Vittoria!” We shall await his presence with bated breath.

Damrau, as his Juliette, was recovering from a recent illness which left her out of the dress rehearsal. Still, hers was a peculiarly non-French traversal of this part, one that emphasized the girl’s rapid development from youthful impulsiveness to considerate adult. Her passage work and coloratura scales were above criticism, so easily did she encompass every facet of her character’s opportunities to shine. Mezzo Virginie Verrez was a quicksilver Stéphano, as was baritone Elliot Madore as Mercutio. His “Queen Mab” air was light and airy, as it should be, yet he showed real bite when the going got rough in his duel to the death with the vengeful Tybalt, played by tenor Diego Silva.

The other citizens of Verona were sung and acted by bass-baritone Laurent Naori, as an authentically Gallic Capulet; bass-baritone David Crawford as Paris; mezzo-soprano Diana Montague (!) as the nurse Gertrude; bass-baritone Jeongcheol Cha as Grégorio; peripatetic tenor Tony Stephenson as Benvolio; and bass Oren Gradus as the grave Duke of Verona. The only cast member who disappointed was bass Mikhail Petrenko as an easily bristled Frère Laurent, his mushy-sounding tones and wavery notes above and below the staff were inadequate for this key character.

Italian conductor Gianandrea Noseda, who has spent the last few years in St. Petersburg, Russia, as the principal conductor of the Mariinsky Theater, in addition to his duties with the BBC Philharmonic, drew splendid brass and string playing from the Met Orchestra. This was not a particularly Italianate reading of the piece, but rather an elegantly conceived interpretation —personable, authoritative where it needed to be, yet stylish and enveloping, with just the right amount of Gallic reserve.

If I have mentioned the hallowed name of Franco Corelli often in this piece, it is because his grand style of vocalism and outsized personality are in desperate need of revival on the world’s opera stages. If the likes of the young Michael Fabiano and Vittorio Grigolo have embraced Corelli’s galvanizing stage presence and formidable technique, then more power to them (and to us).

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements