“My boss never listens to anything I have to say. He’ll ask for my opinion then do just what he was planning to in the first place. Why bother?”

“My employees don’t really care much about their work. The only thing that seems to motivate them is the end of the week. Guess I’ll just have to do it myself.”

Sound familiar? Those are two different views of the same situation. They are mental models in action, and they reinforce a negative pattern of behavior that is ultimately destructive to an organization in many ways.

What are mental models?

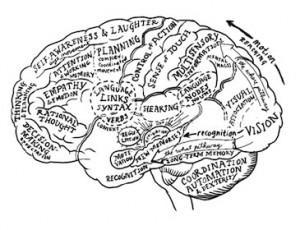

Mental models are deeply ingrained assumptions or generalizations that influence how we understand the world and how we take action. Some other words we use for mental models are perspectives, beliefs, assumptions, and mind set, to name a few. Mental models are often the greatest barriers to implementing new ideas in organizations, but they are also the area of organizational learning where organizations can make the most significant impact.

Unfortunately, assumptions, the word most often used to refer to mental models, have a negative connotation to most of us. We’ve all heard the old adage, “You know what happens when you assume? It makes an ____ out of you and me.” Well, you can fill in the blank. Assumptions, nonetheless, are the only way we can make sense of our complex world. It is not possible to have complete information about every situation we encounter, so by their very nature, our assumptions or mental models are incomplete and therefore flawed. For the most part, however, our mental models serve us well.

There are those occasions, on the other hand, where our mental models lead us astray. A great example of how imperfect mental models can be comes from the ancient parable of the blind men and the elephant, where several blind men are feeling different parts of an elephant and describing it. The descriptions by themselves are inaccurate, but when combined into one, give a clearer albeit still flawed description of what an elephant really looks like. Mental models are like puzzle pieces that we need to fit together into a larger whole. As different mental models are recognized, another piece falls in to place, and we see a clearer picture, but in this work, we do not have the top of the puzzle box to guide us. We must grope along like the blind men.

Mental models affect what we see in situations and create reinforcing patterns of behavior. In the example given at the beginning of this article, the employee sees a domineering and controlling manager, while the manager sees employees who only want to put in the minimum. As a result, the employees become disengaged, and the manager tries to micromanage more – not a very productive situation in any organization. The more the manager tries to control the situation, the more disengaged the employees become, resulting in a negatively reinforcing cycle. The visible part of the cycle, the behaviors, reinforces the invisible part, the beliefs or mental models.

What skills do individuals need to develop?

So how does one break out of this type of downward spiral? The first step is to recognize the gap between what we believe to be true and what is actually true, or to put it more precisely, the gap between mental models and current reality. There are two main areas of skills in which individuals can practice working with mental models:

1) skills of reflection and

2) skills of inquiry.

Skills of reflection involve slowing down our thinking so that we become more aware of how we form our mental models and how they influence our behavior. We can do this in several ways. One way is to become more aware of recognizing when we make what are often referred to as “leaps of abstraction,” that is making generalizations based on our observations with no data to back it up. In the manager-employee example, the employee observes the manager asking for an opinion but then not acting upon it. The employee then jumps to the conclusion that the manger really isn’t interested in subordinates’ ideas. In turn, the manager observes disengagement and concludes that it must be because the employees don’t really care about their work.

One way to avoid this pitfall is to ask the questions:

- “What is the data on which my beliefs or generalizations are based?”

- “Have I ever seen any disconfirming evidence to my beliefs?”

- “Am I willing to consider the possibility that my beliefs may be inaccurate?”

Another method for developing skills of reflection is often referred to as exposing the “left-hand column.” The “left-hand column” represents thoughts we often have during conversations but do not articulate. By actually writing these thoughts down after the fact, we are making our mental models visible. For example, the manager who views his employees as disinterested may call a meeting of his department to announce a new strategic direction for his team.

After presenting the idea, he asks for reaction and is met with stony silence. His immediate thought may be, “Man! What is it going to take to light a fire under these people?” If an employee responds with tepid support, he might also think, “Oh geez! Here we go with the lip service again! Can’t they think for themselves?” Each of these responses reinforces the manager’s mental model, but writing them down makes it possible for him to distance himself enough from the belief to begin to recognize it for what it is, a generalization.

A final technique for developing skills of reflection is to recognize the gap between what we say we believe, our espoused theory, and what we actually do, our theory in use. Put another way, we must start comparing our words to our actions or behaviors. Using the manager-employee example again, the manager may truly believe that participative decision-making creates a productive team, but his behavior is not sending that message to his employees. Until he recognizes that gap, no learning or change can occur.

Skills of inquiry shape how we operate in face-to-face interactions. Once we have begun to practice our skills of reflection, we can then begin to surface and discuss our mental models with others. In doing so, we must remember that our mental models are only pieces to the puzzle. In The Skilled Facilitator, Roger Schwarz has developed a technique called the mutual learning model that can help individuals hone their interpersonal skills. It is based on the assumptions that everyone sees things differently, and it is those differences that create opportunities for learning and creativity. It is also based on the belief that everyone is acting with integrity. One can practice the mutual learning model by:

- Testing your assumptions by articulating them and asking for confirming or disconfirming evidence;

- Sharing all relevant information: withholding information will only lead to a less complete picture;

- Being transparent by putting your thinking on the table rather than your finished thought;

- Focusing on interests, not positions, that is, talking about and agreeing to outcomes before jumping to solutions;

- Discussing those thoughts in the “left-hand column” that are often driving your actions;

- Balancing advocacy with inquiry, that is, asking about other points of view as much as you explain your own.

These skills, in combination with the skills of reflection, will unleash the power to change mental models and to begin moving the organization toward sustainable change. In order to change our behavior we must first change the beliefs upon which those behaviors are based.

How can organizations transform mental models from barrier to leverage point?

Working with mental models is the most difficult place to start building a learning organization but can yield the greatest amount of change. Developing and shaping mental models means changing both individual and organizational behavior – a tall order at best. It is a process that requires patience and perseverance. The following conditions will help organizations reduce the barriers to surfacing and examining mental models:

- Create a safe environment in which employees feel comfortable surfacing and examining their mental models; it must also be an environment where decisions are based on what’s best for the organization, not on politics;

- Help your employees develop their skills of reflection and inquiry;

- Promote diversity rather than conformity;

- Agree to disagree; everyone does not need to agree with the various mental models that exist; each one is just an additional piece of information;

- Be comfortable with uncertainty; we will never know the complete story.

This process requires individuals and organizations alike to change how they think about the nature of work. Once those barriers are reduced, an organization can begin to see mental models become leverage points for innovation. Those negative reinforcing loops transform into upward spirals of success.

In my next article, I will focus on the third discipline of learning organizations, building shared vision.

Author: Marty JacobsArticle Source: EzineArticles.com

© 2011, ©Active Consultants 2011. All rights reserved. Copying in part or in entirety only permitted by written consent

Republished by Blog Post Promoter