The more I work, the more I realize how crucial a tool memory is to the painter. In circles of representational painters, it is a point of pride to paint from life rather than from photographs, and yet this reliance on what is physically before us is of course imaginatively limiting. If our ultimate goal is to so master our super-power that we can uninhibitedly create boundless worlds through our brush, a competence with copying arrangements before our eyes will not be enough. It is simply a step on the way to omnipotence.

Our language is visual, and working from life allows us, if you will, to build our visual vocabulary. It forces us to slow down, pay attention, and battle through each problem of light, volume and texture, of color relationships, of atmosphere, of design. It demands that we are wholly present and alert to the very substances of the physical world: we must pry into the construction of things in a way that word-languages do not. Where our word-brain is content to recognize a chair by ‘some legs and a horizontal bit and sometimes a back,’ our visual-brain needs more information. It notes the turned legs, the crossbars, the torn padding, the ridges, the carvings. But to simply note down these specifics is little more than dictation. Our still lives, if driven by an effort to remember, can serve us more than the image we are currently creating. Draw that chair, paint that chair, and attempt to own it forever.

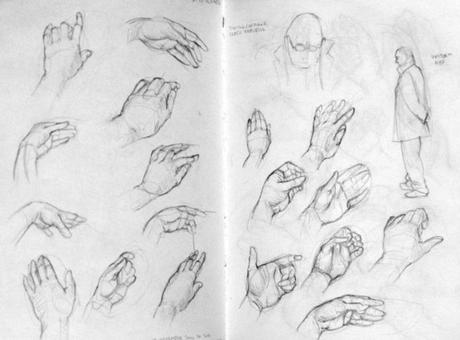

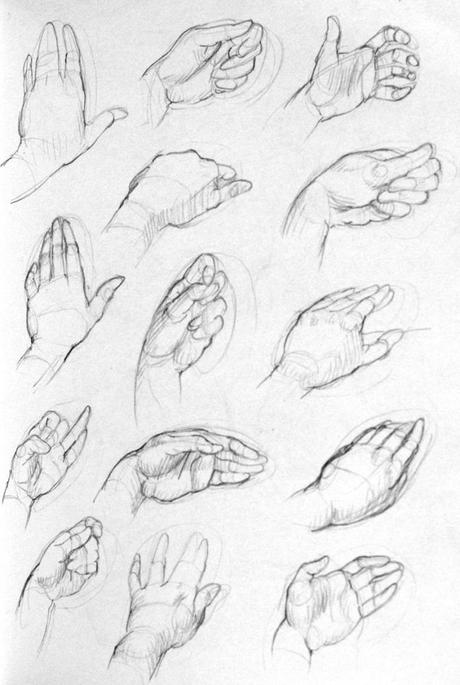

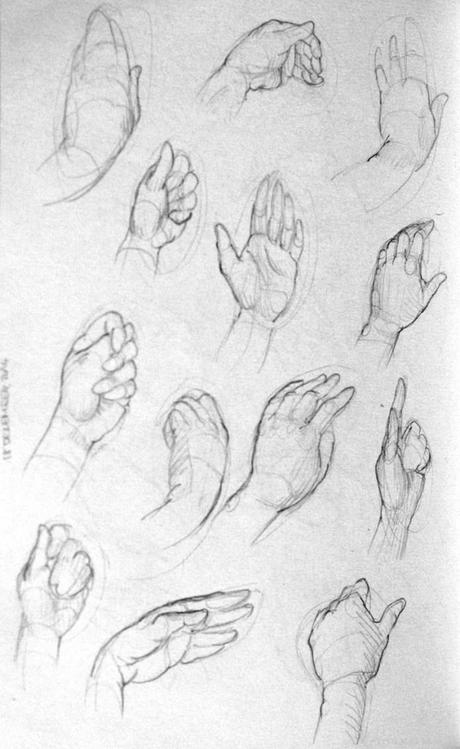

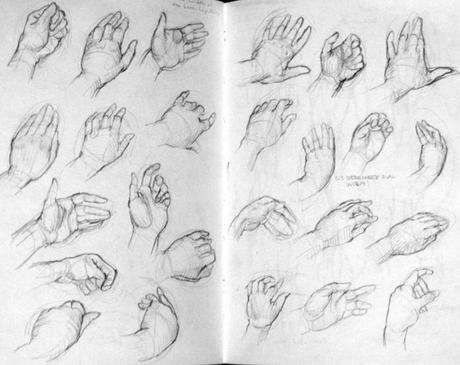

Much of this remembering is physical, in our bodies, learned through motions and repetition. The artist can achieve astounding facility in drawing by nurturing a muscular memory that is not consciously directed by thought. And so, it is not enough to draw; one must redraw. There is no brilliance in fluking a great image, or in transferring a lucky design and colouring the shapes. Repetition cements what we have seen, both in our minds and in our hands. We do well to draw again with greater understanding, greater confidence, a better feel for the image. Through repetition we fuse part of the physicality of an image into our bodies, we store it in the movement of our arms and wrists.

I have started to think of my learning in terms of developing multiple selves, concurrently. This might be as crazy and complicated as it sounds. But it becomes more and more evident that progress in drawing and painting is not strictly linear. Drawing, for example, is not simply the precursor to painting, though solid draughtsmanship is unendingly helpful in painting. For even once we apply our drawing skills to painting, we can continue to improve our drawing. I imagine three selves with three fundamentally different approaches, each supporting and reinforcing the other.

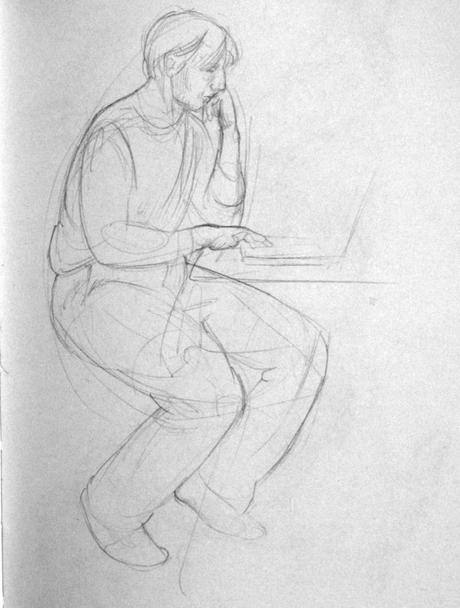

The first self is very literal and rooted in the physical world. She first comes at drawing and painting by observation, and makes great progress with the model or the still life before her. She comes to know what to look for and how to notate it. The external world offers her an abundance of information, stimulus, truths and complexities. Rubens himself was one such dedicated student (Clark, 1985: 133):

‘Rubens copied everything which could conceivably add to his already overflowing resources. For the nude his models were, of course, the Antique, Michelangelo and Marcantonio. Titian he copied for his colour, but altered his form… he drew from the Antique and copied from his predecessors till certain ideals of formal completeness were absolutely fixed in his mind.’

If we neglect this observational self, our visual store is weak and our vocabulary shamefully sparse. All the clever ideas in the world will not make up for our appalling inability to express them visually. Yet the element of memory remains crucial. Ideally, we are not only repeating what we see, but repeating it in order to remember it, so that later we can work from our vast store without needing a model, a chair, a light-source before us. Delacroix (p. 208-9) insists, ‘The only painters who really benefit by consulting a model are those who can produce their effect without one.’

Copy after Titian, Girl in a fur

The second self turns away from the physical world and creates her own, from memory. She is the test of how much we have really internalised. And yet, frustratingly, she starts out almost as frail and helpless as the first did. She draws infuriatingly badly, makes stupid mistakes, forgets seemingly obvious bits of anatomy, and generally lags painfully behind. For this reason it can be easier to smugly rely on our observational self to keep producing lovely pictures. But without abandoning our observational habits, we can also begin to nurture this little self and watch her drawings improve and find to our utter delight that she only strengthens our memory.

A wonderfully modest yet accomplished Berlin painter who demonstrates how powerful such training can be is Ruprecht von Kaufmann. There is a lovely video of a talk he gives to some American students, during which he is repeatedly asked about his ability to paint from memory. They incredulously inquire after his reference material, bewildered at a convincing and detailed chair. ‘Oh yeah,’ von Kaufmann explains off-handedly, ‘the couch is really a rip-off, because one of my most favorite artists is Lucien Freud and he has leather couches like that often in his paintings, so … I sort of looked at how he did it and then translated it into my own way of painting.’

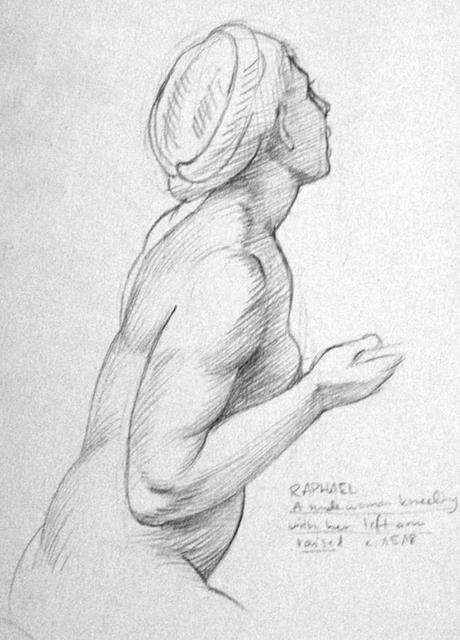

Copy after Raphael

The observational self thus never leaves us; never dissolves or transforms into the imaginative self. Rather, she continues to turn her eyes afresh on the physical world, unrelentingly fascinated. And having trained her memory so well, she might not even need a pencil to own new observations, as von Kaufmann further explains:

‘When I see things that I know that interest me and that I want to use in a painting, I look at them very consciously, trying to break them down into the most simple thing that would allow me to memorise how to put that into a painting and how to represent that.’

And not only can we learn to recreate observations from memory, but, as in the case of Rubens, our observations can be ordered by our imaginative intentions, as Clark (1985: 133) describes. ‘The more we study [Rubens’ nudes] the more we discover them to be under control.’ Once the aforementioned ‘ideals of formal completeness were absolutely fixed in his mind,’ when he approached nature he ‘instinctively subordinated the observed facts to the patterns established in his imagination’ (1985: 133).

And far off in the distance I begin to detect a future self who, supported by her sisters and their razor-sharp memory, no longer needs to prepare with repetition, with fully-resolved studies either from life or from imagination. This self will have such a fount of sure and reliable knowledge, such a fluency with weaving her visual vocabulary into intelligent images, that she will be able to work directly onto the canvas. Her ideas will be well-formed enough in her head, and the movements of her wrist so well tuned to her thoughts that she will be bold enough to investigate in the final medium. And though I’ve no doubt she will struggle as the first, and begin weakly and uncertainly, she will grow in power as she trains her ability to imagine and realize a work.

My most pressing challenge on the way to painterly enlightenment is thus to develop my memory in terms of these differently-focused selves. My recent projects have involved a great deal of memory-exertion, and I will share these with you soon. To be a fully-abled painter of the calibre of Michelangelo depends on ‘a confluence of mental activities, calculation, idealisation, scientific knowledge and sheer ocular precision’ (Clark 1985: 57-8). The burden, then, is on us to look, to really see, and to remember.

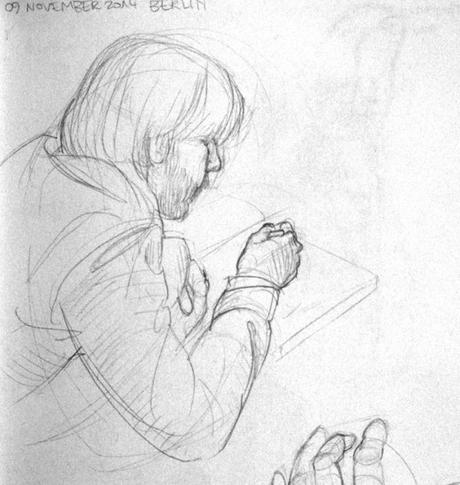

Copy after Franz Hals, Catharina Hooft, Berlin

Clark, Kenneth. 1985 [1956]. The nude: A study of ideal art. Penguin: London.

Delacroix, Eugene. 2010 [1822-1863] The journal of Eugene Delacroix. Trans. Lucy Norton. Phaidon: London.