So Close, Yet So Far …

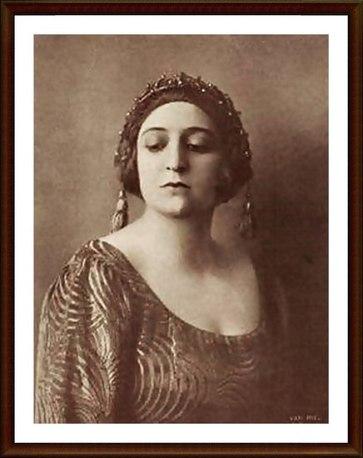

Margherita (Patricia Racette) & Faust (Ramon Vargas) in the Act III duet, “Lontano, lontano, lontano” from Mefistofele (San Francisco Opera)

Margherita (Patricia Racette) & Faust (Ramon Vargas) in the Act III duet, “Lontano, lontano, lontano” from Mefistofele (San Francisco Opera)

Time out for our second intermission feature: we ask the question “What of Arrigo Boito’s own problems with and revisions to his rambling opus Mefistofele?” As we shall see, further study of Boito’s texts for Verdi’s Otello and Ponchielli’s La Gioconda has revealed numerous similarities to individual episodes endemic to both works. Indeed, for years musicologists have been fully aware of the parallels to be drawn from the above pairing.

To cite but a few examples, Alan Blyth, editor of and contributor to the volume Opera on Record 3, made this comment regarding the correlation between the two: “Let it be said that Verdi, or at any rate Boito, took something of Gioconda over into Otello — the plotting, even some of the wording of Act 1, where [the spy] Barnaba is a very obvious predecessor of Iago [note his goading of the crowd over La Cieca’s use of witchcraft, contrasted with Iago’s plying of Cassio with drink], Enzo’s entrance ‘Assassini’ foretells Otello’s ‘Esultate,’ and Alvise’s sardonic greeting to his guilty wife [Laura] that of Otello to [Desdemona] in Act 3 of Verdi’s opera, and above all Barnaba’s ‘O monumento,’ Iago’s Credo.”

This is all well and good. However, more troubling for this writer at least is the never before examined “coincidences” between Boito’s harmonious output for Mefistofele (from the 1875 revival, the Venice production of 1876, and its triumphant La Scala return in May 1881) with those composed by Ponchielli for his final version of Gioconda.

The Otello connection can be traced to the same Opera on Record 3, in the survey by arts critic John Higgins dealing with Mefistofele and its recorded legacy. “It has been suggested that Boito drew on his own Mefistofele when he was creating the character of Iago for Verdi. [Mario] Del Monaco’s performance [in the old Decca/London recording conducted by Tullio Serafin] implies that he might also have had Faust in mind when he was sketching Otello … in ‘Giunto sul passo,’ which Del Monaco turns into Faust’s finest hour in the way that Otello aspires to the heights in ‘Niun mi tema.’”

What scholars may not have noticed is the not-so-subtle melodic “cribbing,” for lack of a better term, of vast stretches of music that permeates the Gioconda landscape. Take, for the sake of argument, that lovely second act ode for tenor, “Cielo è mar” (“Sky and see”). Its rising and falling cadences, “translucent scoring and asymmetrical strophes in the manner of Aida’s ‘O patria mia’” (according to music critic Julian Budden), to these ears smack almost deliberately of Faust’s “Dai campi, dai pratti” from Act I, or his concluding statement, “Giunto sul passo estremo,” from the Epilogue.

To be fair, though, we should point out that at the first performance of Mefistofele the role of Faust was taken by a baritone, which was how Boito had originally conceived it. Because of the similarity in timbre and the monotony in sound quality between Mefistofele (a bass) and the good doctor, he rewrote Faust’s lines to encompass the higher tenor range.

Splitting Airs

Let’s look at the problem from the title character’s point of view. Listen to any of Mefistofele’s scenes, for instance the aria “Ecco il mondo” (“Behold the world”) from the Witches Sabbath. Notice how the music is divided into three sections, how the voice rises and falls with the text. The aria ends on a thrilling high note as the Devil tosses the crystal globe to the ground. From Gioconda’s Act III, scene i, we have Alvise’s “Sì, morrir ella deh!” (Yes, she must die!”) to contrast against. This aria is shaped in like fashion: three contrasting sections, the last of which ends in nearly the same manner as “Ecco il mondo,” although there is no crystal globe to shatter. The bass voice also rises and falls, as dictated by the score.

Moving on to other sections, the first-act tarantella (a sweeping dance number) in Gioconda, coming immediately after Barnaba’s aria “O monumento,” is echoed in Mefistofele’s Act I, scene i, in the episode with Faust and Wagner. There’s also Faust and Mefisto’s gallop, “Fin da stanotte,” that closes the act, which can be juxtaposed against Enzo and Barnaba’s first-act duet, “O nido di quest’ anima,” especially in its concluding section “E tu, sia maledetto.”

Next, we have Margherita’s touching Mad Scene from Act III, “L’altra notte in fondo al mare,” where she recounts her drowning of Faust’s child. Its equivalent can be found in Gioconda’s equally renowned Act IV solo, “Suicidio!” where she contemplates killing herself rather than giving in to Barnaba’s advances. You can evaluate the similarities between Margherita and Gioconda’s predicaments in the coloratura scale passages both characters are called upon to execute, particularly in Gioconda’s final encounter with the spy at the end.

Let’s now take a short sequence from Act II, scene ii of Mefistofele, beginning with Faust’s cry of “Folleto, folleto, velloce, leggier” (“Will-o’-the-wisp, so airy and light”), which bears a striking resemblance in lightness of scoring and mood to that of the Act II introduction to La Gioconda and the scene of the crewmen aboard Enzo’s ship.

Staying with Gioconda’s second act, note how the subsequent Enzo-Laura duet, starting with the tenor’s plaintive “Deh non tremar” and continuing on to the lovers’ joint phrase, “Laggiù nella nebbie remote” (“Down there in the remote mists”), with its delicate harp accompaniment, compares favorably with Faust and Margherita’s Act III duet, “Lontano, lontano, lontano” (“Far away, far away”), also with the aid of harp and strings but in a minor key. The desperate couple’s rising pleas of “La fuga dei liberi amanti speranti, migranti, raggianti” (“The flight of the freed lovers, hopeful, migrant, radiant”) contrast vividly with Enzo and Laura’s more hopeful “Nell’ onde, nell’ ombre, nei venti fidenti, fidenti, ridenti, fuggenti” (“To the billows, the shadows, the breezes, both faithful and smiling and flying”). The obvious textual wordplay, not to mention the swooping vocal lines, stems from Boito’s participation as librettist in both his own work and in Ponchielli’s — in Gioconda’s case, under the pseudonym of Tobia Gorrio.

In the Classical Sabbath section (Act IV), Faust leads off the ensemble with “Amore! Mistero celeste, profondo” (“Love! Heavenly mystery, yet so profound”), followed by Helen of Troy, Pantalis, Nereo, and Satan in attendance. This is matched against Enzo’s melancholic “Già ti veggo,” the lead-off to the famous concertato (or ensemble) that concludes Act III of La Gioconda, with the ballad singer Gioconda, her mother La Cieca, Barnaba, Alvise, and the supposedly “dead” Laura, all present and accounted for. The music is sinuously alike in both examples, with the Gioconda excerpt the more dramatic of the two.

One could go on and on in this vein, but the point has been made. The impression is of the older “established” composer, Amilcare Ponchielli, looking over his younger colleague Boito’s shoulder — and sneaking a peak at his sheet music for Mefistofele. It validates to some degree the conventional wisdom that both men were collaborators as well as friends, even to the point of “borrowing” ideas from one another. There are indeed noticeable differences, along with quantifiable similarities in Mefistofele and La Gioconda, as there no doubt are between La Gioconda and Otello.

To take the issue a step further, noted musicologist Mosco Carner, who wrote the first critical biography of Italian composer Giacomo Puccini, went on the record in his belief that Victorien Sardou, the prolific French playwright whose five-act melodrama La Tosca inspired the Puccini opera on which it was based, may have purloined his plot line from Boito.

“Sardou [was] never too scrupulous in borrowing ideas from other writers,” Carner insisted. Indeed, “the parallels in the story as told by Sardou and by Boito are too close to suggest a mere coincidence. Like Tosca,” Carner continued, “Gioconda is a singer though merely of street ballads; like Tosca, she is of a madly jealous disposition, and this is played upon, for his nefarious purposes, by the Scarpia-like Barnaba, a spy in the service of the Venetian Inquisition; and like Tosca, Gioconda is confronted with the choice of either yielding to Barnaba or forfeiting the life of her lover Enzo; but rather than suffer the fate alleged to be worse than death she stabs herself when Barnaba demands his price.”

Comparably, Floria Tosca may have stabbed Baron Scarpia to save the life of her lover. Gioconda may have stabbed herself to keep the villainous Barnaba from having his way with her. Otello, the Moor of Venice, may have strangled his wife Desdemona, but he also killed himself with a dagger upon learning of Iago’s treachery. And Mefistofele may have lost his wager with Heaven when Faust inevitably asked the blissful vision to “Stay, thou art beautiful.”

While the Devil got his due, audiences can be grateful they will get the best of all possible worlds with opera. Exaggerated? Sentimental? Pretentious? Contemplative? Melodramatic? The operas Mefistofele and La Gioconda are all these things; they also share a commonality of musical styles and interests.

But you can’t keep a good story down (less so in Gioconda’s case), no more than you can keep good music from rising to the fore, as both composers learned soon enough. Out of the tumult of nineteenth-century European culture, the traditional lamb — Ponchielli — sat down with the radical lion — Boito. Together, they concocted two old-fashioned warhorses for the ages.

Isn’t opera grand?

(To be continued….)

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements