It’s intermission time at the online “opera house.”

With that in mind, our feature for today is the much ballyhooed connection between Mefistofele’s creator, Arrigo Boito, and composer Amilcare Ponchielli, resulting in that good old-fashioned warhorse, La Gioconda.

The Scapigliati Get Scalped

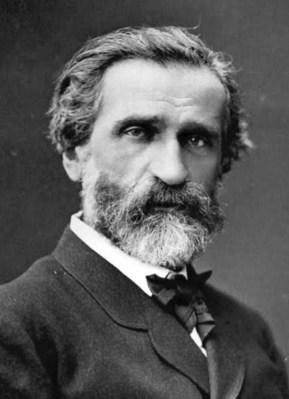

First, some back story. Poet, musician, librettist, composer, essayist, and journalistic firebrand Arrigo Boito (1842-1918), whose birth names were Enrico Giuseppe Giovanni Boito, was at the forefront of one of the most turbulent eras in Italian operatic history — that is, the period before, during and after Verdi’s Aida (1871), and between his penultimate masterwork Otello (1887).

The son of an impoverished Polish countess and a philandering miniaturist painter, as a youngster Boito demonstrated an early aptitude for music and music theory. Enrolling at the Milan Conservatory in 1853, his intellectual drive and insatiable capacity for devouring the great works of literature ultimately steered him in the direction of Faust, Goethe’s epic drama in verse.

On leave from the Conservatory, Boito toured the cultural capitals of Europe (France and Germany among them) where he was exposed to the works of Bach, Beethoven, Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Weber, and ultimately Wagner. Returning to Milan in 1861, his thoughts turned to a massive project devoted to Goethe’s epic poem, to encompass the entirety of Parts I and II. It was considered an enormous undertaking even in the best of times.

Undeterred by the challenge, Boito took up this ambitious scheme with a group of Milanese writers, artists, critics, and musicians known by the collective title Scapigliati, loosely translated as the “Unkempt” or “Disheveled Ones.”

This band of radicals, consisting primarily of poets Emilio Praga, Antonio Ghislanzoni, and Ferdinando Fontana (Puccini’s librettist for his first two operas, Le Villi and Edgar), music critic Filippo Filippi, conductor and composer Franco Faccio (whose opera Amleto was based on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, with text by Boito himself), and numerous others, focused on restoring Italian art, music, poetry, and literature to a more, in their estimation, “exalted plane.” Their cause championed, among other concerns, the incorporation of Germanic precepts, some of which involved the abolishment of formulaic sequences such as arias, duets, and other set pieces (good luck with that!), and the supreme importance of drama.

If the intent was to shake up the so-called Establishment, represented most illustriously by Verdi and the novelist Alessandro Manzoni, then their objective was achieved. Boito threw the first punch at an 1863 gathering of the faithful. In both Mary Jane Phillips-Matz’s meticulously researched Verdi: A Biography and Puccini: A Biography, she records that toward the end of the evening “Boito read a long ode to the health of Italian art. In it he railed against the older generation and added an offensive line that Verdi never forgot. The old men were … ‘idiotic’ and [had] left ‘the altar of Italian art soiled like a whorehouse wall.’”

Verdi was not amused. He fired back with both barrels, confiding to his publisher Giulio Ricordi: “If I, too, among others, have soiled the altar, as Boito says, let him clean it up, and I will be the first to come light a candle.”

Such attacks reaped few rewards for Boito and his fellow Disheveled Ones. Both the high and the low point of their quarrels with the Italian Old Guard culminated in two separate incidents: the first taking place at the 1865 premiere of Faccio’s Amleto in Genoa, which met with some critical success but lacked the public approbation to sustain it; the second at the boisterous La Scala mounting of Mefistofele (the title having been changed from Faust) on March 5, 1868. This performance lasted well past midnight, exacerbated by Boito’s amateurish conducting. Added to which, the cast was not up to the theater’s standards.

In his essay, “Boito and Mefistofele,” for the EMI/Angel recording starring Norman Treigle and Plácido Domingo, Italian language supervisor and stereo production coordinator Gwyn Morris recounted that “On that opening night, the atmosphere was tense, electric in the auditorium, while outside in the square, a huge crowd awaited the verdict. The prologue and the second act quartet in Martha’s garden were well received but the first act displeased the audience who repeatedly booed the rest of the piece … There were heated arguments in the cafés and on the streets about the fiasco until four o’clock in the morning. The following day, the Gazzetta di Milano commented: ‘If a wing of La Scala itself had collapsed, the disaster could not have caused a more violent sensation.’”

Hard to envision today, but incredibly La Scala followed this disaster up with a second performance, this time dividing Mefistofele into two parts (corresponding, more or less, to Goethe’s design) and presenting it on two consecutive evenings (March 7 and 8). Morris noted that the “public response was equally hostile whereupon the police intervened and the opera had to be taken off.” So much for those high-minded principles!

Obviously disappointed yet convinced of its greater purpose, Boito straight away decided on a complete revision of the piece. However due to the loss of confidence he experienced during the three-day affair at La Scala and his inability to compose at will, the composer was forced to modify his plans somewhat.

“The Joyous One”

For the next seven years, Boito occupied his time with writing verses for other composers, as well as tinkering on and off with his piece. We’ve already taken notice of his labors on Amleto, but what most scholars tend to brush off was that Boito, if less than an inspired musician, was a supremely gifted wordsmith. Accepting a fresh commission from Casa Ricordi (who, as far as their music was concerned, had given up trying to get something lucrative out of the Scapigliati) and working under the anagram of Tobia Gorrio, Boito wrote the libretto for the most lasting contribution to all-out Italian passion: Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, or “The Joyous One,” which premiered in 1876, the year after the revised Mefistofele’s return.

Stories of Ponchielli’s mentorship of two music students named Puccini and Mascagni have passed into legend. Though not an official member of the Scapigliati or even holding to their views, Ponchielli nevertheless made lasting friendships with many of the individuals associated with the group. Among those who frequented his summer residence in Maggianico, near Lake Como, were the publisher Ricordi (always on the lookout for a likely successor to Verdi), the Brazilian Antonio Carlos Gomes, the tubercular Alfredo Catalani, the poets Praga and Ghislanzoni, Countess Clara Maffei (a personal friend to Verdi), and, of course, Signor Boito.

That Gioconda is frequently categorized as a “one-hit-wonder” should by no means deny its composer his due. Amilcare Ponchielli (1834-1886) achieved considerable fame during his lifetime with this tuneful, rip-snorting barnburner of a work. One could say that La Gioconda owed as much to Meyerbeer’s invisible hand (his final opera, L’Africaine, was posthumously produced in 1865) and Verdi’s massively conceived Don Carlos (which made its debut at the Paris Opéra in 1867) as to the public’s continuing taste for large-scale stage depictions of raw emotion, religious pageantry, murder, revenge, mayhem, and the like. We must also take Verdi’s Egyptian spectacular Aida into account.

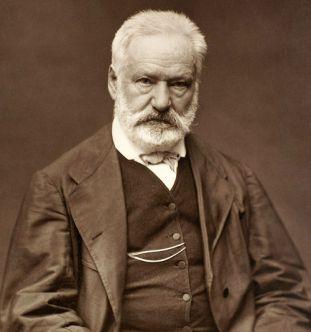

To say that Ponchielli was a slow starter is an understatement. He based his first opera, I Promessi Sposi (“The Betrothed”), on the classic novel by Manzoni, which premiered, in 1856, in Cremona to little notice. Praga refitted the piece with a new libretto for its 1872 revival in Milan. A later work, I Lituani, followed in 1874, resulting in the aforementioned commission to adapt Victor Hugo’s powerhouse tragedy Angelo, Tyran de Padoue (“Angelo, Tyrant of Padua”) for the lyric stage.

Saverio Mercadante tried to make a palatable meal out of Hugo’s grisly melodrama with Il Giuramento (“The Oath”) in 1837, while Carlos Gomes lost his way with Fosca from 1873 (revised 1878). Technically speaking, Fosca was not “directly” derived from Hugo’s work but from an equally scorching 1869 novel Le Feste delle Marie (“The Feast of the Marias”) by Luigi Capranica, a contemporary Roman author. It is well to point out that, on closer examination, the actions of both Hugo’s drama and Capranica’s novel were so strikingly similar (consisting of mistaken identities, thinly-veiled disguises, a feigned death by sleeping potion, spies, secret lovers, and the iconic Venetian locale) one might be tempted to accuse Capranica of appropriating the plot to suit his own purpose.

Writing in the April 1993 issue of the magazine Opera, British-born music critic and scholar Julian Budden went into detail about the genesis of Gioconda and its revisions prior to acceptance as a paradigm of Italian grand opera tradition. “The premiere,” Budden claimed, “given at La Scala on 8 April 1876, with the star tenor Julian Gayarre as Enzo … was an unqualified triumph, the only one of Ponchielli’s career.” He went on to note that “Filippo Filippi, Italy’s leading music critic and a keen champion of Wagner, was moved to pronounce, ‘With the exception of Verdi there is not this day found in Italy any composer but Ponchielli capable of writing an opera of the importance of La Gioconda.’”

There were further additions for the Venice revival six months later: for instance, the ending to Act I featuring the evening prayer and Gioconda and her mother, La Cieca’s, overlapping lines, along with a different number for the bass Alvise (“Angelo” from Hugo’s play). Curiously, Boito’s original text for this showpiece ended with the line: “La morte è il nulla. È vecchia fola il Ciel” (“After death, there’s nothing. And Heaven an old wives’ tale”). If these words have a familiar ring about them, that’s because they are the last lines to Iago’s “Credo” from Act II of Otello — with a libretto written and adapted, as we know, by Boito sans benefit of anagrams.

More revisions followed in 1879 for Genoa, with the lead up being La Gioconda’s inevitable 1880 reappearance in Milan. This series of performances finally helped earn Ponchielli that sought-after post as professor of music at the Milan Conservatory. We can “thank” Boito for assisting him with the myriad transformations that made Gioconda such a massive hit.

In actuality, the above machinations bore the handiwork of their publisher, the resourceful and highly cultured Signor Giulio Ricordi, whose knowledge and taste, keen insight and innate theatrical sense of what the public wanted enabled him to bring these two distinctive artists together — and from opposite sides of the musical fence. This was but a trial run in preparation for a greater challenge that loomed ahead.

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes