[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]

[Cross-posted to By Common Consent]Just so you know, there's probably no way that anyone who doesn't fit into the very narrow Venn overlap of "church-going Mormons" and "Up completists" will be able to understand this post. So that means just about everyone can now safely skip over it.

Just a week ago, I watched Seven Up!, the famous first installment (from 1964) of what eventually became the Up Series, a television documentary series which has followed the same English children for a half-century, revisiting the original (and now middle-aged) subjects every seven years and checking in on their lives. It is, without doubt, the most ambitious and comprehensive documentary film ever made; it's also one of the most compelling works of story-telling, in any medium, that I've ever been exposed to in my entire life. I found it utterly compelling, and over the past seven days I've binge-watched the following eight episodes, for 13 hours of television total.

Several friends have commented to me that while they love the movies, they find watching them difficult, and I can see where the difficulties lie, most immediately with the subjects themselves. Their feelings about periodically being put on display and becoming movies stars of a sort are deeply conflicted, to say the least. But whether appreciative or not, the fact that most of them have continued to participate over the decades is a testament to what they, however reluctantly, can see they have, through the camera, been able to build. As Nick Hitchon (far and away the most intellectually and critically minded of all the series' subjects, though not, in fact, one of the ones most critical of the project itself) kind of indicates in the most recent installment, 56 Up, these films are painful in that they regularly, like clockwork, give the subjects a sense that their whole lives are being unfairly reduced to 10 minutes of interviews and screen time--and yet, in capturing, however fleetingly or invasively or guardedly, the enormous range of accomplishments and failures and strategic elisions and forgotten moments and foreclosed options and lucky turns of event in all their lives, these films are telling everyone's story. The particular becomes the universal, like the greatest works of literature or stage or screen.

These people are around 12-13 years older than me; as the films progressed through time, I couldn't help but compare and think about where I was--professionally, emotionally, personally--when they were at those same points in their lives, and now, having finished the series, I wonder what the next ten years will bring me. Most particularly, I feel a deep affection for these people. Of course, I don't know them, which is actually one of the recurring subthemes throughout the series--as they gained greater maturity over the years and began to interrogate how the camera perceived them and how they perceived themselves, one thing they all agreed upon is that the sense of familiarity viewers have with the films' subjects is pretty groundless. Which is, of course, true--but that doesn't take away from my feelings. I found myself rooting for Tony Walker's marriage, moved by Sue Davis's easy-going determination, surprised and fascinated by John Brisby's aristocratic self-awareness, hopeful for Bruce Balden's moral convictions, admiring of Lynn Johnson's furious, uncompromising compassion, and--of course--frightened for Neil Hughes's survival.

Certainly it would be easy to employ all sorts of sociological sorting in thinking about the series--over the years, economic class, parental decisions, spousal relationship, political changes, and even simply lookism have paid obvious roles in shaping these peoples' destinies. But as the hours went by, that analysis faded away, and instead I came to realize that I could see all of these people reflecting ordinary types of folks that I've known through the communities I've experienced the most over my own 45 years: Mormon wards. In fact, not just reflecting types, but in some sense--if only because my relationship with them is so mediated and selective--exemplifying them. These are people that I wish I could interact with on such a daily, personal basis. For those who are both familiar with how the lay congregations of Mormonism operate, as well as familiar with the Up films, the following designations should be obvious:

Bruce Balden, a child of expensive (and highly restrictive) boarding schools, now a math teacher at St. Albans, is someone we'd all like to be our kids' seminary and institute teacher. Someone whose orthodoxy and conventionality covers--but doesn't suppress--a deep passion for justice, opportunity, and education.

Bruce Balden, a child of expensive (and highly restrictive) boarding schools, now a math teacher at St. Albans, is someone we'd all like to be our kids' seminary and institute teacher. Someone whose orthodoxy and conventionality covers--but doesn't suppress--a deep passion for justice, opportunity, and education. Jackie Bassett, a child of working class parents who had few educational opportunities and subsequently has made more than a few dubious choices and faced more than a few rough times in her life, is someone we'd like teaching in Relief Society, where her lack of pretension, her sarcasm, and her realism would be an often hilarious breath of fresh air.

Jackie Bassett, a child of working class parents who had few educational opportunities and subsequently has made more than a few dubious choices and faced more than a few rough times in her life, is someone we'd like teaching in Relief Society, where her lack of pretension, her sarcasm, and her realism would be an often hilarious breath of fresh air. Symon Basterfield, an illegitimate child who spent years living in a children's home after his father disappeared and his mother had to go to work full-time, and who has slowly overcome his own reserved personality and built a decent life for himself as a father and foster parent, is exactly the sort of straightforward, unpretentious man we'd expect to show up for every elder's quorum service project, and help out with every move.

Symon Basterfield, an illegitimate child who spent years living in a children's home after his father disappeared and his mother had to go to work full-time, and who has slowly overcome his own reserved personality and built a decent life for himself as a father and foster parent, is exactly the sort of straightforward, unpretentious man we'd expect to show up for every elder's quorum service project, and help out with every move. Andrew Brackfield, one of those children whose upbringing and education followed a predictably elite track, and enjoys a rewarding and predictably upper-class professional (corporate lawyer) and family life, would, of course, be the ward's bishop, because leadership always follows reliable, good-hearted people like that. Nothing about him is particularly unpredictable, but do you actually want the leader of your congregation to be unpredictable? Probably not.

Andrew Brackfield, one of those children whose upbringing and education followed a predictably elite track, and enjoys a rewarding and predictably upper-class professional (corporate lawyer) and family life, would, of course, be the ward's bishop, because leadership always follows reliable, good-hearted people like that. Nothing about him is particularly unpredictable, but do you actually want the leader of your congregation to be unpredictable? Probably not. John Brisby, someone who by looks and dress and speech would seem an even more thoroughly predictable creature of the English upper-classes than Andrew, and whose profession as a barrister, whose social circles as a cosmopolitan raiser and dispenser of charity, and whose political beliefs as solidly (if traditionally and not ideologically) Conservative would seem to confirm that judgment, would be the surprisingly cool former stake president in your ward. Orthodox in every way, but with unpredictable streaks of independence, humor, and liberality. Plus, he can pinch-hit with the piano or organ whenever the need arises.

John Brisby, someone who by looks and dress and speech would seem an even more thoroughly predictable creature of the English upper-classes than Andrew, and whose profession as a barrister, whose social circles as a cosmopolitan raiser and dispenser of charity, and whose political beliefs as solidly (if traditionally and not ideologically) Conservative would seem to confirm that judgment, would be the surprisingly cool former stake president in your ward. Orthodox in every way, but with unpredictable streaks of independence, humor, and liberality. Plus, he can pinch-hit with the piano or organ whenever the need arises. Sue Davis, a working class girl who put off marriage, then married late, then divorced, then raised two kids almost entirely on her own, all while building a successful career as an academic administrator and stable relationship with a loving man, would be perfect to serve in a Young Women's presidency. She can use her own life as examples both good and bad, and most importantly her life-embracing, upbeat attitude won't lay down any limits or judgements regarding things which don't really matter.

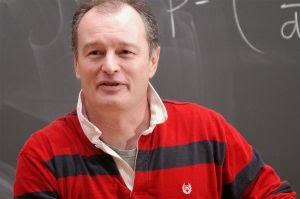

Sue Davis, a working class girl who put off marriage, then married late, then divorced, then raised two kids almost entirely on her own, all while building a successful career as an academic administrator and stable relationship with a loving man, would be perfect to serve in a Young Women's presidency. She can use her own life as examples both good and bad, and most importantly her life-embracing, upbeat attitude won't lay down any limits or judgements regarding things which don't really matter. Nick Hitchon, the farmer's boy who made it from a one-room schoolhouse in rural England to earning a Ph.D. at Oxford and from there to teaching nuclear physics and electrical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is who we'd all want to be our adult gospel doctrine teacher. Articulate, critical-minded, demanding, but deeply grounded in the things which matter most.

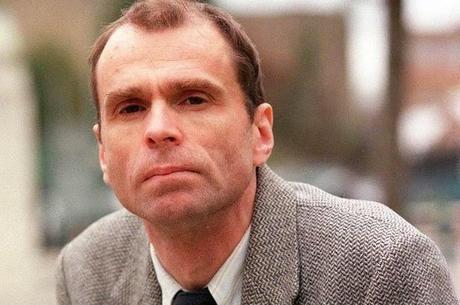

Nick Hitchon, the farmer's boy who made it from a one-room schoolhouse in rural England to earning a Ph.D. at Oxford and from there to teaching nuclear physics and electrical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is who we'd all want to be our adult gospel doctrine teacher. Articulate, critical-minded, demanding, but deeply grounded in the things which matter most. Neil Hughes, a delightful Liverpool kid who grew up paranoid, disturbed, and for long stretches homeless, is the deeply pious but also relentless honest welfare case that every high priests group needs. He'll be difficult and provocative, but he knows things that the bourgeoisie around him don't, and ought to.

Neil Hughes, a delightful Liverpool kid who grew up paranoid, disturbed, and for long stretches homeless, is the deeply pious but also relentless honest welfare case that every high priests group needs. He'll be difficult and provocative, but he knows things that the bourgeoisie around him don't, and ought to. Lynn Johnson another working-class girl who got herself the best education she could, married early, fell in love with her children and determined to make the absolute best for them and everyone like them, is the uncompromising, ball-busting, old-school Labor-voting Primary president (or YW leader) that any ward would beg for. Someone who would take the bishop to task for unequal funding, who would make room for the disabled or struggling in her every children's program, who would push her charges and love them into always doing and learning and being more. (Lynn, I have to say, was perhaps my favorite of all those profiled in the films; her recent death, at the comparatively young age of 57, is very sad.)

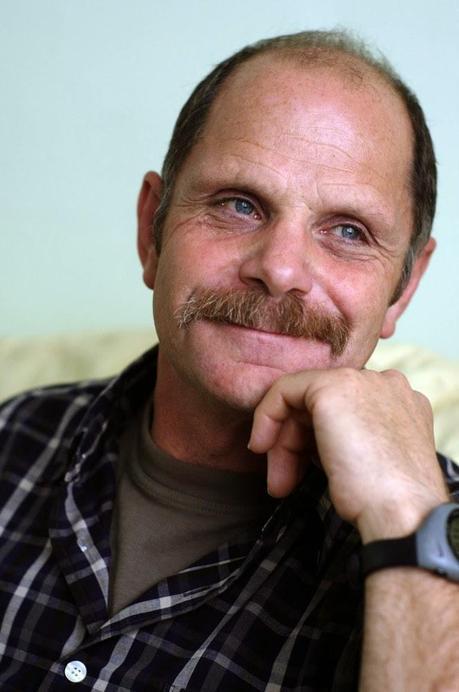

Lynn Johnson another working-class girl who got herself the best education she could, married early, fell in love with her children and determined to make the absolute best for them and everyone like them, is the uncompromising, ball-busting, old-school Labor-voting Primary president (or YW leader) that any ward would beg for. Someone who would take the bishop to task for unequal funding, who would make room for the disabled or struggling in her every children's program, who would push her charges and love them into always doing and learning and being more. (Lynn, I have to say, was perhaps my favorite of all those profiled in the films; her recent death, at the comparatively young age of 57, is very sad.) Paul Kligerman, another product of a broken marriage and a stint in a children's home, who emigrated to Australia to be raised by extended family, and who has since become a handyman with a varying work history, would be the person we'd all want to be bishop, but knew he wouldn't be. He's not educated, organized, or forceful enough. But what he is, as his delightful marriage and family makes clear, is a man of profound and simple wisdom, open-mindedness, and compassion. He and his beloved Susan would be the heart of the ward.

Paul Kligerman, another product of a broken marriage and a stint in a children's home, who emigrated to Australia to be raised by extended family, and who has since become a handyman with a varying work history, would be the person we'd all want to be bishop, but knew he wouldn't be. He's not educated, organized, or forceful enough. But what he is, as his delightful marriage and family makes clear, is a man of profound and simple wisdom, open-mindedness, and compassion. He and his beloved Susan would be the heart of the ward. Suzy Lusk, a girl who grew up privileged, but also scarred by her parents' divorce, would be our perfectly responsible and predictable Relief Society president. No great or surprising wisdom would likely be drawn from her life experiences, but her unflinching determination to not be shaped by her aimless and indulgent teen-age years shows real strength (and her training as a bereavement counselor will likely be of use too).

Suzy Lusk, a girl who grew up privileged, but also scarred by her parents' divorce, would be our perfectly responsible and predictable Relief Society president. No great or surprising wisdom would likely be drawn from her life experiences, but her unflinching determination to not be shaped by her aimless and indulgent teen-age years shows real strength (and her training as a bereavement counselor will likely be of use too). Tony Walker, a kid from London's East End who has been an incorrigible troublemaker and eternal optimist throughout the whole series might be the last person one could imagine in a Mormon ward: after all, he's been a gambler, a player, and as a married man a likely adulterer. But his honesty about his own weaknesses and limitations, his adoration of his wife and children (and now grandchildren), and his tremendous sense of hope is exactly the qualities that a young men's president needs to have. If the boy's need to be taken on a camp out or on service project or just get out and have some fun, he's your guy.

Tony Walker, a kid from London's East End who has been an incorrigible troublemaker and eternal optimist throughout the whole series might be the last person one could imagine in a Mormon ward: after all, he's been a gambler, a player, and as a married man a likely adulterer. But his honesty about his own weaknesses and limitations, his adoration of his wife and children (and now grandchildren), and his tremendous sense of hope is exactly the qualities that a young men's president needs to have. If the boy's need to be taken on a camp out or on service project or just get out and have some fun, he's your guy.Anyone I'm leaving out? Well, I suppose we could make use of Peter Davies, a kid from Liverpool--and friend of Neil's--who dropped out of the series after 28 Up, but recently returned, primarily to promote his band; maybe he could be choir director. And of course there's Charles Furneaux, who hasn't had anything to do with the series since he was 21. He went on to become a journalist, so perhaps he could handle the church program. The folks who do that keep themselves invisible, anyway.