This is the text of my sermon at this morning’s Maundy Thursday Chrism Eucharist for the Diocese of Leeds in Bradford Cathedral.

1 Samuel 3:1-10 & Luke 7:36-50

I find this the hardest service at which to preach each year. Not because of the occasion, but because it is powerfully moving to see so many clergy together. I am immensely proud of the clergy of this diocese who exercise their ministry faithfully week in week out, day in day out, usually unseen. I am very grateful.

I know the feeling. Reading judgements about yourself or the church and feeling that you can’t control the narrative, even when the narrative is either simplistic or one-sidedly erroneous – often in the media. It is particularly irksome when the damage is done from within and by those whose vocation n it is to build up and not break down.

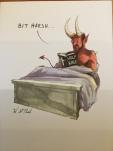

A bit harsh?

The story is this. An ancient middle-eastern man called Elkanah has two wives; one – Penninah -has given him children, the other – Hannah – has not. But, in a surprising reversal of expectation, it is Hannah whom Elkanah loves best. In a moment of tender affection, and after yet another long year of barrenness accompanied by the humiliating ridicule of her fertile fellow wife, he says to her: “Hannah, why do you weep? Why do you not eat? Why is your heart sad? Am I not more to you than ten sons?”

What a question. The answer is clearly “no”. Hannah, deeply distressed, prays that if God will give her a son, she will commit him to a lifetime of no alcohol or grape juice, no shaving or having his hair cut, no hanging around corpses – you can read the full list of Nazirite rules in Numbers chapter 6. My guess is that some of these rules were easier to keep than others. She duly gives birth, weans the boy, then hands him over to the priest. Actually, the text says that she “lent him to the Lord” (verse 28). She lent him.

Now, let’s just step back at this point and notice some of what is going on here. This woman has a hard life: loved by her husband, mocked by her fellow, humiliated in society, and unable to be at peace with herself or others. Yet, she had done nothing to deserve this. Don’t talk to Hannah about justice.

But, the song she sings at this point of blessing-followed-by-loss contradicts what we might assume to be a justified cry for relief from obligation. Couldn’t she break her vow, now that her longed-for son is born? Couldn’t God give her a break – even just to confound the smugness of Penninah? Yet, she sings of hope and freedom, of a God who brings light into dark places and who raises up those who have fallen low. Her song is the one picked up by Mary when her son is about to be born – the deeply subversive song of God’s paradoxical kingdom in which the wrong people are celebrated. The Beatitudes haunt this text, too, like the whispering of melody behind the raging noise of chaos and injustice.

In other words, life is rubbish. Even the good bits don’t satisfy, because other bits keep scratching away like a running sore that won’t stop weeping.

But, then the story moves away from Hannah to the priests at the shrine at Shiloh. If Hannah is the one who appears not to have God’s blessing, then the priests have forgotten what they are there for. The meaning and purpose of the sacrifices have been corrupted to the point that the young priests see the celebration of religious ritual as a means for their own self-fulfilment, power and greed. Religion has become a vehicle for something else. How Shiloh is fallen. And faithful Eli has to hear harsh prophecies about the fall not only of the shrine, but also of his own family. It is a miserable picture that is painted here.

Perhaps the point is rammed home in the reading we read earlier from chapter three. If the old time religion had lost the plot, then God would, as one commentator puts it, simply “bypass the established priesthood and disclose his intentions concerning that same priesthood to a novice”.

A bit harsh?

Well, the picture then looks like this – and I wonder if this sounds a little familiar to us in 2017: “The word of the Lord was rare in those days; visions were not widespread.” Oh dear. Clearly there were many words spoken and many visions propagated in those days; but, how should the people discern the rare words of the Lord amid the cacophony of the shrine worship, political promises, voices claiming to be God’s voice, and religious allegiances? How are they to discern which of the many competing visions of God and his ways is the right vision? How might they work out whether their eyesight is myopic or dimmed? How do they know what is reality and what is truth?

These are hard questions, and they are made flesh in the person of the old priest Eli whose eyesight began to grow dim. He recognised the decline in some of his own perceptions and made space to allow the next generation to grow and to look and to see differently. The errant generation of young priests are bypassed by a God who will not be played off by religious professionals who have lost their sight of the glory of God that once drew them.

And the young prophet – that is, the one who will see clearly the world as God sees it – finds himself addressed by this God … addressed by name and called out to a new service.

Now put yourself into his ephod (as it were). Your mother took a vow that you had no say over. You take a vocational path that did not come to you via the careers officer. And, if her own life had been tough and contradictory enough, she has now shared the misery with you by bequeathing you a life not of your choosing, but of obligation anyway.

Yet, Samuel accepts this and makes this vocation his own. He chooses to go with it, discovering as he does (and as he grows as a person and as a prophet) that life is pretty messy and that there is no place for the self-indulgence of rights and self-fulfilment. Obedience is not a popular word, but it is one that has a place in the life of those who do not complain about their lot, but choose to make the best of what they have inherited.

I just wonder if this text, this story, has anything to say to us here in the Church of England, in the Diocese of Leeds, today? Maundy Thursday, when we re-live that poignant moment at which Jesus confounds convention, kneels at the feet of his friends – and of his betrayer and his denier and his doubter – and washes their feet. Maundy Thursday, when we see Jesus calling his people back from the manipulations and seductions of power and religious game-playing, and asking them to watch and listen and learn and do. Maundy Thursday, when he knows that life is closing in, that suffering awaits, that he could escape it all, but chooses the way of obedience.

After all, this is the same Jesus who, as we heard earlier, has a knack of bringing out of embarrassing dead ends something surprising and new. A woman intrudes into a party at which she is not a guest, and weeps all over Jesus, anointing his feet with expensive oil. The stand-off between propriety and humanity is electric as everyone waits to see which way Jesus would jump. In the end, as Tom Wright puts it, “Jesus keeps his poise between the outrageous adoration of the woman and the outrageous rudeness of the host” and comes up with something fresh and unexpected … and outrageous to those watching whose religion is fairly simple: keep the rules, avoid dirty people, and prioritise your own purity. Read the story: Jesus turns convention on its head and pours out grace where harshness had dominated.

I think both these stories hit on the same point and address us today with hard questions. Do we number ourselves with the religious professionals who have lost the plot, or do we allow ourselves to be outraged by grace … being grasped once again by the power of mercy? Do we rail against the call of God and the demands or privations of an obedient priesthood, or do we deliberately choose life and joy and commitment to an obligation we would sometimes rather throw off? Do we complain about our lot – especially when it seems inherited or not our fault or not by our choice – or do we, like Samuel, accept the choosing of God and get on with it, learning as we grow?

I don’t ask these questions glibly – or miserably. I ask them because I think they cry out from the texts we didn’t choose this morning. There might be much that we find irksome about the Church of England in 2017 – but, we are part of it and called to serve in it as clergy or lay disciples and ministers. If this is the case, then we must love the church as God’s gift and the locus of his vocation. This does not mean that we sit back and let it be; but, it does mean that we pray like Hannah and don’t mock like Penninah. It means that we pray and shape an uncertain future, conscious of our obligation to future generations to bequeath the faith that makes such demands of us. It means that we be open to hear the prophetic witness that questions our priorities, our attitudes and behaviours, challenging us to recover the vision that contradicts the easy visions and learns to listen for the word of the Lord that is – remember – rare, but not absent.

Our readings today invite us to take responsibility for the calling God has given us – to be faithful in our time to the gospel that draws and drives us. Not to blame other people or other generations for what we have inherited, but to take responsibility for accepting what is and helping make it what it might become. We might refer to this dynamic in words such as ‘loving, living and learning’.

Our diocese is nearly three years old. We began with no infrastructure, no governance, no integrated data, no inherited vision, not even the right number of bishops to do what we were being asked to do. We faced many challenges and it sometimes seemed that all the odds had been stacked against us making this work. But, thanks to the hard-won commitment, faith and – sometimes reluctant – persistent generosity of both clergy and laity, we started this year as a single entity. I do not take this for granted.

But, the challenges have not gone away. We face financial challenges and we must address the declining numbers of deployable clergy available to us in the coming decade and beyond. We will face the challenges posed by buildings and structures, and by people who do not want to change. We will see again that people and places thrive when they grasp the opportunity to choose change and don’t see themselves as victims of someone else’s terrible or malign decisions. Remember, Easter chants the mantra that we are not driven by fear, but are drawn by hope.

Brothers and sisters in Christ, if our feet are washed by the Lord who kneels before us in humility, should we not speak well of one another, seek the best of one another, and believe the best of one another? Should we not be generous, even though we know we kneel before our denier, our betrayer, our doubter? Are we not called back to a vision of love and mercy and grace that pulls out of polarised tension something new and fresh and hopeful? Do we believe ourselves invited as a church to shine the light of mercy on the intrusive woman and not just to show our cleverness in embarrassing the Pharisee?

We come today to re-affirm ordination vows and to recover the priority of our own discipleship of Jesus Christ. In doing so we allow the light of his face to shine into the dark places of our own prejudices, judgments and fears, leaking grace like an extravagant ointment onto the tired and dusty feet of our faltering journeying. And we pray that the Lord whose church we are, and whose beloved we are told we are, will anoint us for the next stage of our ministry – as a diocese, as ministers of the good news, as disciples and followers of Jesus.

Here I am, for you called me. Here I am, for you called me. Here I am, for you called me.

Advertisements