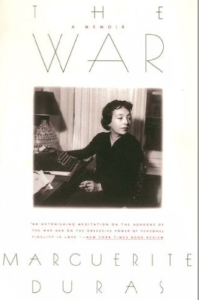

Marguerite Duras’ affecting book The War – La douleur is a collection of texts based on her war diaries. Before beginning my review, I have to mention that I’ve read the French edition and don’t know how close to the English it is. It seems that the two last texts, two short stories, have been left out in the English edition but I could be wrong. I’m not going to review them here. Each of the texts covers another time period.

1945

La douleur – The pain is the first text in the book and is also the longest and appears to be the only one that she left as she found it. Duras said that she couldn’t remember writing this diary and that, to her, it seemed more powerful than any of the literary texts she’d ever written. La douleur, which was written during April 1945, describes in painful details, how Marguerite Duras waited for the return of her husband, Robert L., a member of the resistance, who had been deported to Buchenwald in 1944.

Duras managed to convey the anxiety of those waiting and the incredible difficulties to take care of someone who came back. They knew to which camp Robert had been brought and so, knowing the Germans had lost the war, they followed the news closely and went to the centres to which those who returned came and questioned them. Duras knew that Buchenwald had been liberated, but she didn’t know if by that time Robert was still alive. Once she found someone who had seen him, there was still the fear that he might have been among those shot by the fleeing Germans. Why, she wonders did they shoot them just minutes before the arrival of the Allies? In Buchenwald alone 51,000 were shot, while 20,000 survived. Possibly, he was among the survivors but if so, he might still die of exhaustion or an illness. A little later, when they hear that the German cities are literally burning, another anxiety joins the fears she had before. He might be trapped in a fire storm and get killed that way.

In the end, two of her friends travel to dacha (Robert had been moved a few times) and bring him back. Before they arrive, they warn her – she might not recognize him. The tall man weighs a mere 38 kilograms and looks horrific. He’s very ill and his survival is almost a miracle.

1944

Monsieur X – Pierre Rabier is the second text in the collection. It describes the cat-and-mouse game a Gestapo official plays with Marguerite Duras. He pretends her husband hasn’t been deported yet, meets her often, wants to have an affair with her. He may think he’s the stronger one, but Duras plays a game with him as well. She learns everything about him and later uses it to help sentencing him to death.

After the war

Albert des capitales and Ter le milicien both describe how Duras and other members of the resistance take part in torturing and forcing people to give them information that will lead to their or other people’s sentencing. In these two pieces she changed names and wrote about herself in third person, calling herself Thérèse.

I wasn’t sure what to expect from this book. I’m familiar with Marguerite Duras and love her writing but I still thought this would be just another WWII memoir. It isn’t. Most memoirs fous either on the war – on the battle field or the home front – or on the camps. I don’t think I’ve ever read a memoir by someone who was waiting for someone and about the challenges of the return. There’s so much going on in these pages. Every day, there’s a new anxiety regarding her husband and every day the people in France find out more details about the war. The French sent 600,000 Jews to the camps. One in 100 came back. They didn’t know any details about the camps until the end of the war. Other arresting details capture that for France the end of the war also meant the end of the occupation. Or what it was like to see Paris at night illuminated again.

As I wrote before, some of the texts deal with what happened to collaborators. Duras seems to have taken an active part in their arrest and punishment. I couldn’t help but wonder what I would have done. I can absolutely not imagine myself watching someone being tortured or even torturing someone.

There were also aspects that were especially interesting for me, as a French person, because the liberation and its aftermath, the coming to power of de Gaulle have led to problems France is battling to this day. Marguerite Duras mentions that de Gaulle only wanted to emphasize that the Allies won the war. He didn’t mention the camps, nor did he want them mentioned because it had to be about glory not about pain. Possibly this explains the choice of title because she thinks you have to discuss the pain. You have to hear the people who suffered. I’m afraid that the logic behind not mentioning the camps isn’t only linked to “glory” and such. If you don’t talk about the camps, you don’t need to talk about those who were deported to the camps and the people who sent them there. Ultimately, this leads to the refusal to admit responsibility and the denial that there were collaborators.

French politics aside, this is one of the most important WWII texts I’ve ever read. The writing is tight, evocative and detailed, just what I had expected from Marguerite Duras.

Other Reviews

*******

The War – La douleur is the fourth book in the Literature and War Readalong 2017. The next readalong is dedicated to war poetry. Discussion starts on Wednesday 31 May, 2017. You can find further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2017, including the book blurbs here.