It would, perhaps, be an office worthy the labors of a good commentator to explain certain great players who routinely rehearse lofty ideas such as heaven, hell, righteousness, judgment or genius, and about whom, it is reasonable to believe, very little at present is left to be understood. In modern times it will be pretty difficult to find anyone who’s greater or more hard-working than Messi and Maradona—fellow country-men, almost inseparably annexed to a life of glory, and so supremely gifted that, indeed, anyone who’s seen them in action would find hard to walk away without blushing.

Many readers and soccer gentlemen have contracted a general profligacy to entertain an opinionated discussion on whether the senior legend or his younger heir can be said to be the greatest player of all times; concerning this opposition, which (as I’d argue) carries little practical use, it is also customary to feign total ignorance. Instead of undertaking this task myself, however, I will try to assemble a learned glossary of these two exceptional players, fashioned in the manner of Flaubert’s Dictionary of Accepted Ideas.

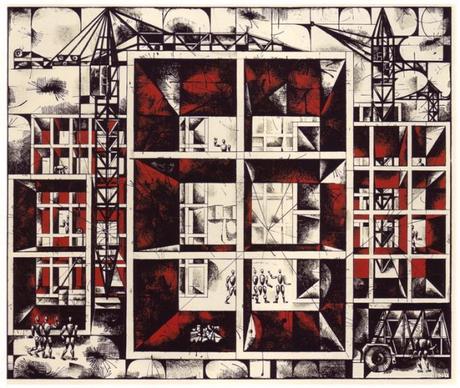

Surely, Maradona and Messi, as an artifical memory bank of the game, signify the decentring and destabilization of soccer knowledge that seems to be such a feature of current computer-driven approaches to tactical storage, transmission, and retrieval. Maradona, with his hyper-masculinized and theatrical embodiment of the number 10, represents a patriarchal figure in a world of linear thinking. Messi, one of the falsest among the false 9s, emphasizes the ‘female’ embrace of horizontal networks, a belief of discord and digression, and thus represents a departure from the traditional taxonomies of football. Diego’s career has been a brute force (and one would always feel in it the blemishes and raw beauty of the favela). While his pitches were often swamped like marshes and frustrated defenders, at his sight, sustained themselves with raw-dealing and sincere faith in the Madonna, Messi’s modes are more attuned to a philosophical mind (and, consequently, one would be better advised to see how a team like Barcelona made him who he is rather than the other way around).

A key method of Messi is condensation—all the pith and marrow are made to be portable, each digression creates a loop away from the main 3—4—3 text, amplifying images and forming a collage by association. With the decline of the older system, Maradona became, in many ways, a transitional figure between hermetic and mechanical views of soccer, or between the solitary and ‘masculine’ pursuit of greatness and Guardiola’s (distinctively feminine) suggestion that football could use metaphors of marriage, union, and merging to describe its aims of ultimate fluidity.

Gianni Brera has famously identified styles of playing in soccer which separate along gender lines: there are and always have been, in his vision, ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ teams. Yet, even the Italian reputation for fixity in defensive mechanisms is quick to point out that these differences are matters of preference, and that there is some crossover between the sexes. A glossary of Messi/Maradona is justly owing less to male planning than to female bricolage. Bricolage, at least according to Claude Lévi-Strauss, literally means pottering, doing odds and ends, negotiating from corollary to corollary, rather than from axiom to theorem. Bricoleurs are also like soccer players who do not use outlines, but start with one idea, associate to another, and find a connection with a third. Fearsome bricoleurs like Maradona, moreover, are always more likely to produce a Bride of Frankestein, moving as if after an electric jolt, while the work of the Horatian Messi unfolds through intertextual links, as though the Muses of soccer decided to pay service to the polite part of mankind. ♦

← Glossary →

Argentina. The name of a woman, commonly of a very bad one.

Artificial. The chamber of soccer memory, imagined by the Renaissance computer as a universal library, where the whole of Ovid’s Metamorphoses are digested in eight sheets of tackles.

Barcelona. The best place for a Sunday stroll.

Bear. A country defender; or, indeed, any player who goes for the knee-cap without making you a handsome bow.

Beauty. The qualification under which a mistress and a good performance generally goes into keeping. (DM, a great favorite of all women, is different from LM, whose outward decency implies a touch of shyness and restraint.)

Brute. Tassotti. (Also see Bear.)

Captain. A piece of multi-colored ribbon wrapped on your arm, any stick of wood with a head to it, and a quality expression properly confined only to the mouths of honorable radio speakers.

Coach. A laughing stock; it means likewise a poor fellow, and in general an object of contempt.

Damnation. A proper term for the retellings of an old Lady Macbeth by the fireplace, though sometimes largely suitable to all works of invention of both LM and DM.

Death. Never the final end of these two men, but only of the thinking part of their socer bodies, as of all the other parts.

Dribbling. The principal accomplishment of man.

Dullness. A word applied by all critics to the wit and humor of other players.

Eating. For DM, a science; for LM, centuries of moths and bookworms.

Falkland Islands. A kind of traffic carried on in wartime between two countries, in which both are constantly endeavoring to cheat each other, and both are commonly losers in the end.

Fine. An adjective of a very peculiar kind, destroying, or, at least, lessening the substantive force of these two players: for fine passes, fine crosses, fine movements, fine through-balls, fine taste—all which is fine on the pitch is to be understood in a sense somewhat synonymous with useless when you’re so great.

Fool. A complex Shakespearean idea, compounded of poverty, honesty, piety, and simplicity in the fourth-man by the stadium side-line.

Foot. Applied to these two, signifies great happiness; when to a common man, often meanness.

Free-kick. Powered with ceaseless spell by both LM and DM, it is the name of four cards in every pack.

Gallantry. Fornication and adultery.

Hand. The portal of touch. (See also Falkland Islands.)

Happiness. Fame.

Honor. Duelling.

Humor. Tumbling and dancing on the goalkeeper’s rope.

Judge. A cunt.

Justice. An old woman.

Mischief. Fun, or pastime.

Modesty. Nonsense.

Naples. For LM, a city of a different party from yourself; for DM, one of the few things upon earth that is really valuable, or desirable.

Nobody. All the people in Great Britain, except about 1200.

Patriot. A candidate for a coaching place after retirement.

Politics. The art of getting such a place.

Religion. A word of no meaning, other than for the inane habit of depicting both players as Messiahs, but which serves as a Catholic bug-bear to frighten children with.

Rogue (or Rascal). For DM, a man of a similar party from yourself.

Taste. The present whim of the Gazzetta dello Sport, whatever it be.

Teasing. Ending a footballing action; also, an advice, chiefly that of a husband.

Temperance. Want of spirit.

Wit. Prophaneness, indecency, immorality, scurrility, mimicry, buffoonery; abuse of all good men, and especially of the refereeing clergy.

Worth. Power. Rank. Wealth.

Wisdom. The art of acquiring all three.

World. Your own acquaintance.