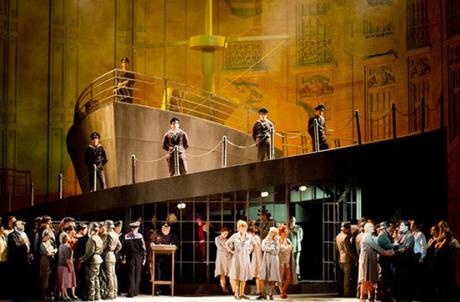

Des Grieux (Roberto Alagna) & Manon (Kristine Opolais) in Act IV of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut (Photo: Ken Howard)

Des Grieux (Roberto Alagna) & Manon (Kristine Opolais) in Act IV of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut (Photo: Ken Howard)Life Imitates Art

They were known in the classical music world as the “love couple.” One critic went so far as to portray their tempestuous on-again, off-again relationship as the operatic equivalent of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s rocky road to paparazzi ruin.

Now that the so-called love couple are officially divorced (for the second time, at last count), French tenor Roberto Alagna and Romanian diva Angela Gheorghiu have gone their separate ways, with little to no love lost between them. This may or may not have been news to their many fans and followers, but it has most certainly liberated Monsieur Alagna (and her, as well) from the constraints imposed on them with regard to Madame Gheorghiu’s appearance with other artists.

One example of the fiery tenor’s art was revealed when he participated in the Richard Eyre production of Bizet’s Carmen from 2010, alongside the stunning Latvian mezzo Elīna Garanča. Their sensational fourth act duet, wherein one had the uneasy feeling Alagna’s pathologically obsessed, go-for-the-jugular Don José may have had its antecedents in real life, led to rave reviews for both artists. Personally, I’d like to think that Alagna’s performance was due to superior acting skills, but who can tell given his past history.

Back in 2013, when he and Gheorghiu agreed to a definitive breakup, rumors kept flying that Alagna was having trouble tempering his insanely jealous character over his then-wife’s pairing with singers other than himself — specifically, that dark-haired German dreamboat, Jonas Kaufmann. Whether these were the exaggerated claims of over-zealous reporters or based on actual evidence, the truth is Alagna has been welcomed back into the Met Opera’s fold with arms wide open, thanks, ironically, to Herr Kaufmann.

This came about primarily to Kaufmann having begged off the highly anticipated new production of Puccini’s Manon Lescaut by claiming an indisposition. Exchanging places in Pagliacci with the robust-sounding Marco Berti, Alagna saved the day when he consented to take Kaufmann’s place in a staging conceived and designed by Mr. Eyre. Berti would go one to reward listeners as the tragic clown Canio in the return of the Met’s Cav and Pag from last season, as well as Calaf in Zeffirelli’s extravagant Turandot (recently reviewed by yours truly in the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2016/07/04/sprinkle-a-little-turandot-seasoned-with-a-dash-of-cav-and-pag-part-two-cast-reshuffling-and-dueling-high-notes/).

In addition to literally learning the Chevalier des Grieux at the last minute (a part he had not previously sung), Alagna also agreed to continue with his previously scheduled assignment of Lt. B.F. Pinkerton in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Both Manon Lescaut and Butterfly would feature the Met’s latest singing sensation from Latvia, spinta soprano Kristine Opolais, in the title roles.

With that, the transmission of Manon Lescaut took place on March 5, 2016, while Butterfly was heard a month later on April 2. Met principal conductor, Fabio Luisi, presided over Manon, with Karel Mark Chichon pulling yeoman duty in the Butterfly broadcast.

The Past is Prologue to the Present

Unlike Puccini’s first two attempts, the two act Le Villi (1884) and the unsuccessful three-act venture Edgar (1889), Manon Lescaut was the one piece into which the fledgling composer poured all his heart and melodic soul. It was the only full-blown triumph of his career from among his twelve works for the stage (twelve, that is, if you count the one-act Il Tabarro, Suor Angelica, and Gianni Schicchi, for Il Trittico, as three separate items).

First and foremost, Puccini gave the principal male lead, that of the love-struck Chevalier des Grieux, his most daring and most emotionally incisive music. In no other Puccini work was the tenor called upon to provide the musical and dramatic thrust of the barebones plot. In doing so, Puccini ignored the advice of practically everybody, including his publisher Giulio Ricordi, not to tackle a theme in which two illustrious predecessors, the Frenchmen Daniel Esprit Auber and Jules Massenet, had earlier engaged in. That’s all Puccini needed to hear to get his creative juices flowing at full tilt.

A pillar of the French opéra-comique repertoire and highly regarded at the time, Massenet’s five-act Manon was not even a decade old when the ambitious Puccini, itching to leave a mark on the operatic stage, hit upon a subject that fit his personal preferences. The main problem, however, was in how to reshape the novel into something an Italian audience might sink their teeth into. Puccini refused to work again with poet Ferdinando Fontana, the librettist for Le Villi and whom the composer blamed outright for Edgar’s ignominious failure at La Scala. Instead, Ricordi assigned the portly Ruggero Leoncavallo the task of dealing with the rambunctious Tuscan.

Equally unsatisfied with the results, Puccini immediately dropped Leoncavallo — who went on to greater heights of his own with Pagliacci — for two other poets, Marco Praga and Domenico Oliva. They, too, soon fell by the wayside. It was at this point that Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, two formidable men of letters who would eventually form the successful triumvirate that resulted in La Bohème, Tosca, and Butterfly, were thrown into the fray. Puccini balked and bellowed, as well as labored on the project for two years before submitting the finished work for publication and performance. Incidentally, Puccini took sole credit for Manon Lescaut, having left out the contributions of so many hands, including that of Ricordi and the composer himself!

The original novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux at de Manon Lescaut, written by a defrocked priest known as the Abbé Prévost, was an alleged autobiographical depiction of the Chevalier’s doomed affair with the beautiful but unprincipled young heroine, Manon. To pare the story down to its essentials and steer it in the direction of the male protagonist (who is also the book’s first-person narrator, much as Don José would be for Prosper Mérimée’s novella Carmen), Puccini lavished the tenor with no less than four major solos, three solid duets with the soprano, and that blockbuster third-act ensemble.

In the early going, the mood is light and carefree, with nary a hint of the plight to come. There are spirited choruses in Act I; an upbeat tune for Des Grieux, “Tra voi belle,” which many might equate with the Duke of Mantua’s opening arietta, “Questa o quella,” from Verdi’s Rigoletto; Des Grieux’s brief encounter with Manon, the outgrowth of which is his attractive solo, “Donna non vidi mai,” literally “I’ve never seen a girl like her”; their subsequent duet (picking up where they left off) in which they plan to run away together; the rich roué Geronte’s fuming at her elopement with the impoverished Des Grieux; and her brother Lescaut’s “soothing” comment to the old man that Manon’s flighty, ambiguous nature ensures that she will tire of the boy soon enough.

For listeners, the biggest leap of faith — and the oddest, most confusing turn of events — occurs in Act II wherein Manon has already left Des Grieux for the coiffed elegance and perfumed ambiance of Geronte’s palace in Paris. Manon assumes the role of the old geyser’s spoiled and pampered mistress, a part she was born to play. The main interest here is the delicate scoring throughout, including a minuet; the Dancing Master’s foppish presence; and the Madrigal Singer’s airy little song. Admittedly, Puccini’s youthful attempts at capturing the decadence of pre-Revolutionary France fell flat, with the exception of Manon’s wistful lament, “In quelle trine morbide,” one of those distinctively long-lined melodies the composer would later be noted for.

About midway in the act, when the decadence of the preceding scene has ended and all parties have left the stage, including Manon’s avaricious brother Lescaut, who should burst in but her ex-lover Des Grieux. Immediately, the music takes a serious turn. You can sense that Puccini was finally about to embark on a voyage of emotional volatility, buoyed by an overpowering dedication to Italian melody. Audiences literally gasp at the change of mood. In a veritable explosion of one memorable hit tune after another, Puccini sets the stage for his lone paean to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, a work he became familiar with when, as a struggling youth under Ricordi’s wing, the publisher had sent him to Bayreuth in the foolhardy task of trimming the German composer’s Ring cycle into a palatable one-night affair.

Reunited at last, the lovers rediscover one another and, in the final section, depicted in the orchestra and in their rising vocal lines, their mounting tension is released and resolved as Manon and Des Grieux are enveloped in love’s rejuvenating power. Whew! From here on end, the opera takes off as few Italian works of the period have, with the notable exceptions of Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci.

The only letdown is the dreary quarter-hour that encompasses Act IV, written entirely in a minor key. This act must surely have been an afterthought, an appendage that Puccini or his publisher decided on in order to wrap the proceedings up in a tight bow. It has never worked to the complete contentment of opera houses. In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, NYCO put on a new Frank Corsaro production of the work that, contrary to that innovative director’s prior accomplishments, did not entirely satisfy either (mostly due to poor casting of the leads).

Although this piece is a far cry from what may be termed standard-issue verismo — curiously, it was influenced by Germanic precepts, in much the same way that Alfredo Catalani’s Loreley and La Wally had been — Manon Lescaut placed Puccini squarely on the map of his country’s rising stars. By all accounts, the opera assured his ascension as the successor to the great Giuseppe Verdi’s mantle.

One for the Record Books

Consequently, the part of Des Grieux was tailor-made for tenors. It has attracted such A-list interpreters as Giuseppe Cremonini, who sang it at the opera’s 1893 Teatro Regio premiere in Turin, Enrico Caruso, Beniamino Gigli, Francesco Merli (Toscanini’s favorite tenor), Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, Giuseppe di Stefano, Mario del Monaco, Richard Tucker, Carlo Bergonzi, and Plácido Domingo.

Speaking of which, Des Grieux was Tucker’s preferred part and one he cherished above all others. The few recorded extracts he left behind, to include notable appearances on the Ed Sullivan Show, along with the aria, “Guardate, pazzo son,” with the CBS Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Alfredo Antonini (the CBS network’s answer to NBC’s Arturo Toscanini), provide an excellent showcase for Tucker’s communicative powers and his ability to move listeners with his tone. The voice, distinctive as always, easily rode the orchestral accompaniment, and his commanding top notes explode to a convincing climax. His is an obviously affecting conception.

In comparison, Alagna as Des Grieux had the right Latinate touch, albeit lighter and more pointed than the usual heavy dramatic sound. He forced his lyric instrument mercilessly, though, opting for volume and power in the climaxes. Not by nature a spinto tenor, Alagna nevertheless lent dignity to Des Grieux’s exclamations of undying ardor. Of all the singers, he was the most committed to portraying his character’s purpose for being: that of the self-sacrificing victim of love.

Needless to say, his ideal diction overcame any lapses in legato, which was not always seamless. For an artist relatively new to his part, Alagna came through basically unscathed, unleashing a torrent of sound for his big moment in Act III: “Guardate, pazzo son,” was devastating in its impact, as it should be at this juncture. Des Grieux is pleading with the ship’s Captain to take him on as a cabin boy, just so he can be with his beloved. He was passionate to a fault. Still, I’d watch those prolonged high notes if I were him, where Alagna’s voice veered off into sharpness.

In director Eyre’s re-imagining, Manon Lescaut takes place in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War. Straining credibility to the breaking point, I found the concept a trifle forced at the outset, but later taking flight in an extraordinarily convincing Act III, helped considerably by the massive set (courtesy of designer Rob Howell) of an ocean liner at port. Act I was equally impressive with a nearly full-scale train occupying the stage.

The concept itself, that of Manon as a film noir heroine participating in the era’s intrigues, sort of like Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant in Notorious, or Bergman and Bogart in Casablanca, two foreign fish out of sea water, came together in Act IV — usually the most problematic of the opera’s four, as indicated above. One critic stressed the similarity of this act to that of bombed-out Warsaw (see Polanski’s The Pianist with Adrien Brody as protagonist). Actually, Des Grieux and Manon return to her Act II abode, now a ramshackle wreck, where the heroine expires from exhaustion.

The capricious heroine in question, sung as well as acted to hysterical perfection by the opulent-voiced Kristine Opolais, had her ups and downs. I was struck by the similarity in timbre to that of the late Renata Tebaldi, one of the major interpreters from the 1940s and ‘50s of this difficult part. Indeed, Ms. Opolais channeled that rich Tebaldi sound, with its unmistakable creaminess and fullness, in her moving depiction of “In quelle trine morbide,” and especially in her last act “Sola, perduta, abbandonata.”

Kristine’s performance was all the more distinguished for its refusal to rely on phony theatrics, or to turn the aria into a maudlin display of self-pity. In that, for the most part she was restrained. Through no fault of her own, however, the audience laughed at the scene of Manon’s gathering up of her valuables. Both Opolais and Alagna’s highpoint came in their sizzling act-two duet, “Tu, tu, amore tu!” Hot, sexy, and bothered, she and her erstwhile lover engaged our sympathy with their ample charms and vocalism. Kristine did a mild striptease, while Alagna helped take off her high heels. They wound up on the couch, but then moved over to her bed for a bit of over-the-top love-making. Divine! That was the moment when Geronte (debuting bass Brindley Sherratt) broke in on the action.

Despite his late-hour assumption, with one eye on Kristine and the other on the conductor Alagna still managed to caress the vocal line, lingering on the phrase “O tentatrice” (“Oh, you temptress”), where he admits that Manon has once again bewitched him, as Opolais went into her lounge act. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Could this be the Met’s new love couple?

As Lescaut, baritone Massimo Cavalletti, who I admired as Marcello in the company’s La Bohème of a few years ago (featuring Opolais’ outstanding last-minute substitution as Mimì), offered a blustery interpolation of her venal brother. I liked the old-fashioned Italianness of his interpolation, which reminded me of that dependable Met Opera stalwart, Philadelphia’s own Frank Guarrera in his prime. Sherratt was a grumbling Geronte, ample in voice and physical presence, in this production a Nazi sympathizer. Another debutante, tenor Zach Borichevsky, was a mellifluous Edmondo. Philip Cokorinos’ brief lines as the Innkeeper kept things rolling, with Virginie Verrez, Maria D’Amato, Scott Scully, Brandon Cedel, Andrew Bidlack as the Lamplighter, and Richard Bernstein as the Captain, contributing positive turns.

The best performer of the lot, however, remained maestro Fabio Luisi. Of all his previous outings, this was Luisi’s finest hour and most compelling conducting assignment. The famous Intermezzo, which begins Act III and describes Manon and Des Grieux’s flight to the port of Le Havre, was superbly played by every member of the Met Opera Orchestra. Fabulous Fabio made the strings sing, eliciting a taut, consistently focused sound unlike any I have heard before in this music. It’s Wagner’s Liebestod, or Love-Death Italian-style!

Luisi’s contribution to the success of this production can go alongside that of Toscanini’s, who presided over an historic La Scala revival of Manon Lescaut in the early 1920s — a revival that gave lasting recognition not only to this work but to Puccini himself as standing at the apogee of Italian operatic composers.

(End of Part One – To be continued…)

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes