By Billal Ali (see bio at end)

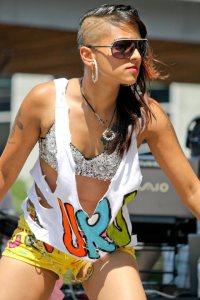

Her flattened blond mohawk peeks out from underneath the black toque. The recording studio located in a west Toronto basement, which Urvah says used to be a freezer, unfortunately retains the utility of its past function. Complimenting the winter hat, Urvah wore a black v-neck sweater-vest over a button-down, camouflage patterned dress shirt. The tattoos representing her band (The CNS), musical accomplishments, and spiritual journey were hidden from plain sight. However, underneath the faint studio lighting, half covered beneath the army-print collar, peeks out the, “Je ne regrette rien,” hand-written across her neck— a fitting sentiment for a life fully lived and filled to the brim with fated turmoil. Her calm, polite, and obliging manner betrayed the aggressive, screaming stage persona. My earlier prediction of being choked with a guitar chord was looking less and less likely.

The Past

Urvah is the daughter of a Mechanical Engineer and Journalist, as well as a distant relation of Pakistani pop singer, Nazia Hassan. She was born in Karachi; Pakistan and raised in Abu Dhabi before emigrating to Canada at the age of twelve. The re-location from Abu Dhabi to Flemingdon Park, a tough Toronto neighbourhood, came with its consequences. Urvah tells me that while the Canadian government places a high value on educated and skilled immigrants, international experience rarely allows individuals to re-enter their field of expertise. “Its heart breaking to know that your parents come from good backgrounds, and have their Masters… and there’s your Mother —one of the most prominent journalists from Pakistan working at a factory.”

Mounting tensions caused the cultural conflict to rear its head. Urvah, insisting it was due to the nature of the UAE school system, was skipped ahead taking grade 12 and 13 courses at the age of fifteen. As a result, she made older friends —friends who she describes, “wore a lot of makeup and had boyfriends.” Urvah’s moderate-Muslim parents were deeply concerned over the possible corrupting influences this new society offered. They wanted to protect their daughter; unfortunately, their well-meaning actions resulted in agitating restrictions. “School would end by 3:20. My Dad would be out there by 3:10,” Urvah recalls. Subsequently, she dropped out of high school and ran away from home just before her 16th birthday.

She concentrates on her hands and describes the event in retrospect, “I’m not proud of my decision because I hurt my family a lot, and until today we still pay for the decisions each one of us has made.” Despite the remorse in her tone, Urvah admits that, for her, the decision was necessary. I interject with a question, “Did you run away, or did they kick you out?” She responds back quickly, “My parents would never kick me out. I ran away.”

Urvah spent the next 7 years, finding herself, to use a cliché. One month after running away, she had already converted from Islam to Christianity— an action that further complicated her familial relationships. It was the classic, bold, adolescent move of wanting to discover ones own path rather than inherit what was given. Urvah reminisces about her first time in Church, “Everybody was jumping and dancing. They were rejoicing in the lord and I’m like, what is going on? Why are you dancing? It’s like a club in here,” she laughs, and then interpolates, “I think that’s really the first time I felt the power of music.” Urvah’s Christianity seems to reflect a broad ranging, holistic spirituality infused with what she sees as principles of equality and fairness, rather than being a set of moral beliefs.

From church bells to police sirens: “…Actually it was twice,” Urvah admits hesitantly responding to the number of her jail stints. The crimes revolved around theft— the second of which nearly had Urvah tried as an adult. Devoid of pride or false humility, Urvah laments and contextualizes her actions, “I never want people to think that I’m claiming to be some hotshot big gangster because I’m not— I’m not a gangster. I was just a kid who was trying to find my way,” she says with sincerity, “I never got my life back together until I was in my early twenties.”

Exorcizing a ghost of her past, Urvah went back to school to get her GED and for a short period of time attended University. At 22 she landed a job as an account manager but was eventually laid off. Not wanting to waste her time, Urvah, indulged a spark of passion and downloaded some free beats and started rapping. Her writing abilities were admired, however friends suggested that she not rap— and they were not the only ones. This was the beginning of her music career.

Lacking formal musical training and stage experience, Urvah’s first performance went badly. Incorrectly gripping the mic, her voice came out muffled and unclear. And, not being used to the bright stage lights, Urvah avoided looking at the audience focusing instead on the floor. A fellow performer disparagingly suggested she write for others rather than perform. However, with the encouragement of the show promoter, who detected something more, Urvah went back to the drawing board. Vindicated, during her next performance she opened for known Canadian singer and song writer, Danny Fernandez. Although, to be fair, getting her friend to pose as an agent from Universal may have tilted the scales in her favour.

The Music

Urvah describes her music as “Rock meets world.” Instrumentally, the sound is composed of a variety of drums, staple heavy guitars, and electronic sounds peppered with hints of a South Asian flavor. Vocally, Urvah switches back and forth between straight forward singing and rhythmic, half-sung half-spoken rap verses. The lyrical flow alludes to an evident soca influence detectable in both pronunciations and slang. Urvah further articulates a strong vocal emphasis by strategically delivering specific lyrics with a shouting, screaming liberation. The content seems to reflect deeper themes easily dismissed at face value. A purist more than a pragmatist, Urvah insists that both the content of her videos and lyrics reflect sincerity in the portrayal of herself.

“Rock is dead,” is a phrase Urvah often espouses, although she denies doing so flippantly. Urvah specifically references how musical fads tend to cause an over-saturation of artists less driven by inherent passion and self-expression. Giving me a crash course in rock history, Urvah explains its evolution from African American slavery, to jazz, and eventually to what most people know as rock; all the while referencing the likes of Chuck Berry, Elvis, Queen, Black Sabbath and Kurt Cobain. She describes what she believes to be the essence of rock, “Rock comes from an oppressed soul. It comes from a person who just wants to be free and can’t be. Every time there was a movement there were these bunch of kids who just wanted to say something. Nobody has anything to say anymore.” Contrasting the past with the present, Urvah attributes corporatisation and mass monetization as factors that contribute to the status quo. In an all encompassing sense, her independent “scrap” rock is a contribution to a new movement dedicated to the resurrection of what once existed.

With her ability to overcome and persevere, it’s quite easy to paint Urvah Khan as role model; however, she seems to hate the charge— partly out of humility and partly due to the shackling implications the phrase can imply. In spite of this, Urvah prefers to think of herself as a positive influence. “I want to inspire people. Inspiring people is different from being a role model or an ambassador for a brand. I’m not perfect. I’m far from it. I want people to take and be inspired by the goodness, and I want them to forgive me for my sins.”

Her new, first full length album, “The Wrath of Urvah Khan,” can be downloaded by visiting her site http://www.urvmusic.com/. She’s scrappy, but also extremely friendly, and often asks her fans to be in her music videos. She can be reached on twitter @URVlive.

About the Author

The Studly Billal

Billal is a Toronto based freelance journalist and satirist currently attending the University of Toronto. His website, www.iambillal.com, often addresses controversial issues pertaining to South Asian culture, Islam and social politics with a view that is both progressive and pragmatic. Outside of the more touchy subjects, Billal talks about men’s fashion and local cuisine, or as he prefers to call it, clothes n’ food. If you wish to contact Billal, he’s a very friendly guy who always enjoys receiving feedback and interacting with people— at least in theory. However, more than anything else, Billal takes aggressively moderate pleasure in writing short autobiographies in which he refers to himself in the third person.