Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990) was a much-read English left journalist, critic, and international observer and a close friend of George Orwell in the 1930s. Muggeridge wrote an introduction to Orwell's novel Burmese Days, and along with Tony Powell, he made arrangements for Orwell's funeral in 1950. (Ian Hunter's Malcolm Muggeridge: A Life provides an excellent biographical study.)

Muggeridge was a strong supporter of the Communist Revolution in Russia in the 1920s, but in 1932 he served in Moscow as a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian and came to see the horrific side of Stalinism. In 1933 he traveled to North Caucasus and Ukraine to observe the process of collectivization and starvation that was underway there, without permission from the Soviet authorities, and some of his articles were published as "our correspondent" in the Guardian in March 1933. A second batch of articles was published in the Morning Post in June 1933 (link).

Here is Muggeridge's 25 March 1933 Guardian article (the first of the Guardian series):

Living in Moscow and listening to statements of doctrine and of policy, you forget that the lives of a hundred and sixty millions of people, mostly peasants, are profoundly affected by discussions and resolutions that seem, as abstract as the proceedings of a provincial debating society.

"We must collectivise agriculture", or "We must root out kulaks". But what is going on in the remote villages? I set out to discover it in the North Caucasus.

A little market town in the Kuban district. There were soldiers everywhere - well fed, and the civilian population was obviously starving. I mean starving in its absolute sense; not undernourished, but having had for weeks next to nothing to eat. Later I found out there had been no bread at all in the place for three months.

The famine is an organised one. The proletariat, represented by the G.P.U. (State Political Police) and the military, has utterly routed its enemies amongst the peasantry who tried to hide a little of their produce to feed themselves. The worst of the class war is that it never stops. First individual kulaks shot and exiled; then groups of peasants; then whole villages. It is literally true that whole villages have been exiled.

About 60% of the peasantry and 80% of the land were brought into collective farms, tractors to replace horses, elevators to replace barns. The Communist directors were sometimes incompetent or corrupt; the agronomes were in many cases a failure. Horses, for lack of fodder, died off much faster than tractors were manufactured, and the tractors were mishandled and broken. Collectivisation was a failure. The immediate result was a falling off in the yield of agriculture. Last year this became acute. It was necessary for the Government's agents to take nearly everything that was edible.

There took place a new outburst of repression. Shebboldaev, party secretary for the North Caucasus, said in a speech: "At the present moment, when what remains of the kulaks are trying to organize sabotage, every slacker must be deported. That is true justice. You may say that before we exiled individual kulaks, and that now it concerns whole stanitza [villages] and whole collective farms. If these are enemies they must be treated as kulaks'.

It is this "true justice" that has helped greatly to reduce the North Caucasus to its present condition.

And here is the second article from the Guardian on March 27, 1933, recording Muggeridge's observations from his travel to North Caucasus and Ukraine (link). Here is a striking passage from this entry:

How is it that so many obvious and fundamental facts about Russia are not noticed even by serious and intelligent visitors? Take, for instance, the most obvious and fundamental fact of all. There is not 5 per cent of the population whose standard of life is equal to, or nearly equal to, that of the unemployed in England who are on the lowest scale of relief. I make this statement advisedly, having checked it on a basis of the family budgets in Mr Fenner Brockway’s recent book Hungry England, which certainly do not err on the side of being too optimistic.

In the evening I joined a crowd in a street. It was drifting up and down while a policeman blew his whistle; dispersing just where he was, then reforming again behind him. Some of the people in the crowd were holding fragments of food, inconsiderable fragments that in the ordinary way a housewife would throw away or give to the cat. Others were examining these fragments of food. Every now and then an exchange took place. Often, as in the little market town, what was bought was at once consumed. I turned into a nearby church. It was crowded. A service was proceeding; priests in vestments and with long hair were chanting prayers, little candle flames lighting the darkness, incense rising. How to understand? How to form an opinion? What did it mean? What was its significance? The voices of the priests were dim, like echoes, and the congregation curiously quiet, curiously still.

Here is a short excerpt from the second article in the June 1933 Morning Post series (link):If you go now to the Ukraine or the North Caucasus, exceedingly beautiful countries and formerly amongst the most fertile in the world you will find them like a desert; fields choked with weeds and neglected; no livestock or horses; villages seeming to be deserted, sometimes actually deserted peasants famished, often their bodies swollen, unutterably wretched.

You will discover, if you question them, that they have had no bread at all for three months past; only potatoes and some millet, and that now they are counting their potatoes one by one because they know nothing else will be available to eat until the summer, if then. They will tell you that many have already died of famine, and that many are dying every day; that thousands have been shot by the Government and hundreds of thousands exiled; that it is a crime, punishable by the death sentence without trial, for them to have grain in their houses.

They will only tell you these things, however, if no soldier or stranger is within sight. At the sight of a uniform or of someone properly fed, whom they assume, because of that fact, to be a Communist or a Government official, they change their tone and assure you that they have everything in the way of food and clothing that the heart of man can desire, and that they love the dictatorship of the proletariat, and recognize thankfully the blessings it has brought to them.

Much of the deadly reality of Stalin's war of starvation against the peasants, the Holodomor, was concealed or minimized by western journalists in Russia. John Simkin (link) provides a very illuminating description and critique of the western journalists stationed in Moscow during the early 1930s who minimized or denied the occurrence of mass starvation, including New York Times reporter Walter Duranty and UPI correspondent Eugene Lyons. Both Duranty and Lyons attempted to discredit Gareth Jones, whose travel through Ukraine in 1932 represented one of the earliest eye-witness accounts of mass starvation there, along with Arthur Koestler and Malcolm Muggeridge. (Here is an excellent discussion with Anne Applebaum of the important film Mr. Jones; link.)

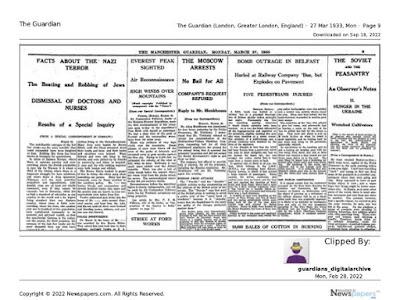

The Guardian provides a reproduction of the relevant page of the newspaper for March 27, 1933, the date that Muggeridge's second article appeared. It is striking to see the traumatic history represented on that single page of newsprint: Nazi oppression and violence against Jews in Germany, Stalinist arrest and persecution of workers in Russia, an Irish bombing, and hunger in the Ukraine (link). (Click the image for a more legible resolution of the page.)