We find ourselves in a unique time as beer lovers. Everything and anything is available to us. Whatever we want, whenever we want it.

With a record number of breweries nationwide, more than 5,000 businesses are creating a vast array of styles and flavor experiences, often nearby where we live. According to the Brewers Association, roughly three-quarters of drinking-age adults in the U.S. live within 10 miles of a brewery.

The flip side of this freedom of choice is the natural competition that comes with it. Keeping an IPA on tap is important to satiate American drinkers' love for all things lupulin, but today's brewery faces challenges presented by all the other entrants into the industry, roughly two a day. Finding a niche, or, at least, creating one, is a pivotal part of the business, whether it's as a brewery as a whole or simply providing novel experiences every time someone walks through taproom doors.

Increasingly, the process of creating something "rare" is playing a larger role for brewers. This could be a celebrated one-off beer with limited quantities or a dedicated tap on-location that serves creations never to leave the premises. As businesses grow, evolve and consider how best to position themselves, the use of rarity in all its varieties has potential to impact breweries, industry tastemakers and drinkers.

While naturally assumed, whether through practice or thought exercise, beer as an experiential good has great power to affect our emotions, both through its alcohol content and the psychological reaction of consuming something that simply tastes good. In a 2017 study published in Food Quality and Preference, researchers found that information related to ABV alone may have enough impact to activate positive emotional responses. Using "regular" and non-alcoholic beer, researchers found that "liking" scores among Dutch participants were more closely aligned with the real thing, especially when non-alcoholic beer was actually labeled as "real" beer.

"This change in liking seems to be a reaction to the product name rather than to the flavour of [non-alcoholic beer]. As an extrinsic attribute, the product name is a powerful tool in the communication between products and consumers, creating specific sensory expectations through prior associations and experiences of consumption," they wrote in their findings.

This point emphasizes the power of our expectations. Because we have to taste and experience beer in order to judge it, our assumptions play a strong role in perception. Choice impacts not only our purchase decisions, but potentially perceived outcomes, too. "When choice is involved, emotions can play a deeper role," researchers noted.

If you have the full ability to make selections based on personal criteria, your choice can lead to a stronger emotional connection, which in turn may create a deeper appreciation for what you consume, particularly if it's something special or rare. Our preconceived notions can impact our reactions if and when it's around the social construct of beer. The psychological, sociological and emotional connections made over a person, brewery or brand are nothing to scoff at, especially when the essence of what "craft beer" stands for - authenticity - means so much.

At the core of what has helped drive the "craft beer movement" in recent years is the abandonment by many of the set of experiences macro beer once monopolized. While accounting for just 12.2% of American beer sales by volume in 2015, craft beer isn't only seen as a product, but a statement in consumer choice. The idea of "industrialized beer" has made way to the romanticized process of artisanal development, our brewers toiling away over a steaming mash tun or testing hundreds of barrels, "hand crafting" every batch just for us.

That's a little tongue-in-cheek, but only half so. "People buy products not only for what they can do, but also for what they mean," Sidney Levy wrote in 1959. To many, craft beer represents the antithesis of mass produced lager. No matter how much truth is in our Hero Brewer working hard for our small-batch IPA, it still represents the thing we're after: authenticity.

In recent weeks, research and opinion presented on this blog have worked to tackle this topic through the lens of rarity, a connection that, at least anecdotally, only seems to be getting stronger. Audiences value authentic goods for what they represent, explains Pierre Bourdieu, and observations of the beer industry suggest the most authentic beer, and therefore most valued, just happens to be the kind very few can get.

This connection can be found elsewhere, with restaurants (higher ratings) and movies (higher demand) impacted by levels of interest and the amount each is deemed "mass market." The same has been suggested with beer, hinting that products made by breweries such as AB InBev or MillerCoors are devalued because they aren't as "authentic."

"Consumption and evaluation are, fundamentally, social acts," Justin Frake writes, highlighting a pivotal point in the evaluation of beer: the experiential and physical component of rating can be as important as the nonphysical, mental portion.

Appearance, aroma and taste influence the perception - and, ultimately - rating of a beer, but there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the ethos of craft, setting itself aside as an oppositional force to macro beer, hits its apex with the limited and one-off beers that perform so well among "best" beer lists. These are often the epitome of time and labor (barrel-aged sour/wild, imperial stout, etc.), or present a wholly unique experience unavailable on a large scale (NE IPA).

These qualities of rarity - also perceived as truer examples of authenticity - have ranging impacts. "If a beer's quality is not perfectly observable to the consumer," Frake writes, "then they may use the commonly perceived association between authenticity and quality to make quality inferences."

This also relates to taste expectation, which has shown to influence perception and consumption, but also assimilation to expected norms. The prestige of a product - not necessarily counting its actual level of quality - can force a cycle in which authenticity equates to quality.

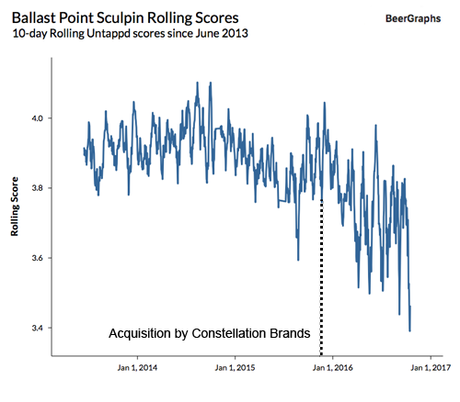

In October 2016, BeerGraphs explored this idea, asking the question of whether Ballast Point's acquisition by Constellation Brands could have altered the scores of its flagship IPA, Sculpin, on Untappd. The range of scores varies from pre- to post-acquisition and demonstrates a downward trend in consumer appreciation.

Two conversations around possible answers arose from this:

- The acquisition did, in fact, influence how drinkers thought about Ballast Point, therefore impacting their scores.

- Because Sculpin became more widely available, it was no longer as "special" to find and also faced issues of sitting on shelves longer than usual, perhaps impacting flavor.

In both these cases, the underlying argument is based on the authenticity of the business and brand. Regardless of which train of thought may be more applicable, ratings still appear to have declined, or, at least, demonstrated a wider range of potential scores, most notably in the lower end of the spectrum. This is important, as Frake found that RateBeer users who were aware of a craft brewer's corporate ownership reduced ratings after an acquisition to the factor of about a 3% penalty.

"These results suggest that consumers devalue inauthentic organizations (craft breweries owned by corporate breweries) because they perceive them as having lower symbolic value," he writes.

Similar findings were presented in the Journal of Wine Economics, where researchers showed ecocertified wine - a product set apart by sustainably-certified production and the difficulty that comes with it - sees its ratings change depending on availability. Researchers at UCLA concluded that an ecocertified wine increases its expert scores by 4.1 on average, but as cases produced increases, scores go down. "A 1% increase in the number of cases will decrease the scaled score by 0.019 point," they found.

Even with an honest approach to business - something I do not doubt - a craft brewer has a built-in, psychological way to game the system. In fact, it's long played an important role to tell the story of craft beer. As we've all likely seen and experienced, the "us vs. them" scenario is a large part of the industry. And, "if small organizations are considered more authentic, then authenticity may be one of the few competitive advantages that entrepreneurs have over large incumbent firms," Frake proposes.

Connecting all the dots above, we can then assume that not only does the organization (brewery) benefit, but also the product it provides (beer). It's a trickle-down effect: an authentic brewery creates an authentic product which is able to reach its most authentic state as a limited or special product.

But that's not the only way we judge the value of a beer, consciously, subconsciously or even biologically.

By nearly all measures, the cost for limited or rare beer is high, not just in actual dollars, but time and effort devoted to obtaining it. This alone has an ability to make something seem to have higher quality.

If we accept that rarity and authenticity go hand-in-hand to influence our perception of beer, then we must also consider how those aspects impact the price of the product and what it does to us. In previous research, it was shown that for many consumers, there is a threshold of how much they're willing to pay for certain flavor experiences. However:

Humans are irrational, capable of leading with our heart as much as our brain. Even more, financial decisions can be heavily influenced by past decisions - old habits die hard whether actually good or bad in the long run. When discussing the potential for beer prices and what's to come, we need to keep in mind the established marketplace and what behaviors are already the norm.

In this case, the effect of rarity on ratings can also impact price and what we're willing to pay.

"...higher consumer ratings are associated with higher prices, such that a 10-point increase in an average consumer rating is associated with about a 50-cents increase in the price of a unit (i.e., a six-pack) of beer," a group of researchers wrote in Agricultural and Food Economics.

With limited research performed with beer, it's worth looking to wine to better gauge what price does to perception. One study found that "a 1-point increase in the personal opinion (the difference between score and objective quality) raises price by approximately 8% on average."

And what price does to us - in all its forms - matters: "...perceptions of quality are known to be positively correlated with price." The higher the cost, the better our brains perceive something to be.

In 2007, a group of researchers from the California Institute of Technology and Stanford University put this to the test, looking to match the business and marketing of wine to our body's reaction. What they found indicated that the willingness to rate something highly isn't just a sociological cue, but a biological one, too: "...increasing the price of a wine increases subjective reports of flavor pleasantness as well as blood-oxygen-level-dependent activity in medial orbitofrontal cortex, an area that is widely thought to encode for experienced pleasantness during experiential tasks."

The assumption of quality creates an actual, chemical reaction in our brains.

Two experiments were run, the first showing subjects reacted positively when presented with information about wines of higher price points, and the second, presented with no price information, exhibited no reported differences. It's a classic example that mirrors the beer blind taste test - the kind seen so often in the beer community where Pliny the Elder is dethroned as the country's best IPA once you remove the name and hype around it.

Together, the ideas and assumptions around authenticity, cost and what it means to be "rare" bring into focus characteristics of what it takes to potentially be "best" among thousands of other options. As we've seen in the beer world, that list is continuously narrowed not only based on those traits, but what kind of beer is made, too.

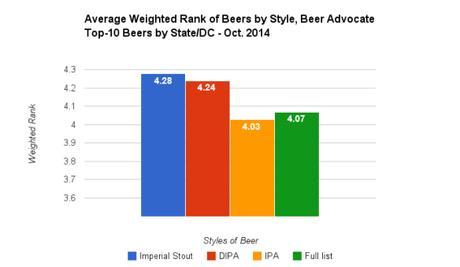

For years, we've known that imperial stout, IPA and double IPA have dominated rating lists. Going back to 2013, it's been tracked on this blog over and over with prominent online sites like RateBeer and Beer Advocate. For example, here's the averaged weighted rank of styles from data I pulled in late October 2014, a dataset that included 507 beers comprised of the top-10 beers (or fewer, if less than 10) from all 50 states and D.C.:

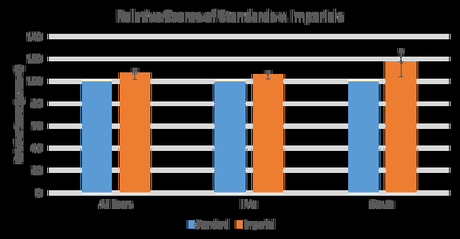

In case you're wondering why "regular" IPA may have been lower than the average of the 507, it's worth pointing to 2013 research from BeerGraphs, which found a difference in Untappd ratings based on ABV levels:

Most recently, the success of these styles was tracked on this blog in terms of their characteristics and - to an extent - rarity, which showed a strong preference toward big stouts and hop-forward pale ales as seen on the top-250 from Beer Advocate:

...and BeerGraphs:

In my own analysis from this fall and looking back to past years, the prominence of these styles is impossible to ignore as preferred representatives of what is typically cited as "best." In just about every case of inclusion in lists and rankings, brands of imperial stout and IPA variants feature aspects of authenticity and rarity previously discussed, suggesting that there may be a correlation between the perceived quality and how beloved some brands or styles have become.

This was recently demonstrated by two researchers analyzing online beer ratings by drinkers in Finland. In a paper published in December 2016, Petri Niemela and Niels Dingemanse aimed to determine the accuracy and value of online ratings, but also provided a finding that emphasizes stylistic bias of drinkers which we've seen before. The styles of beers with highest scores, according to participating Finns, were imperial stout, baltic porter, imperial porter, eisbock, barleywine, double IPA and black IPA:

Without knowing the collected beers presented to participants, it's hard to draw specific conclusions aside from basic aspects of these styles: they are high in alcohol content, adhere to specific flavor groupings, are among the most labor and ingredient intensive styles, and, because of all these things, have higher potential to be rare or limited as well. Of note in their findings:

"...styles that include heavily roasted malts such as stouts and porters, which are typically black or almost black in colour, and have chocolate, coffee and roasted tastes and aromas are rated highest by the Finns. Generally, types of lager like malted liquor, pale lager and helles, all of which include relatively small amounts of malts and hops and use brewing techniques and yeasts specific for those styles, were rated below average."

The researchers neglect to discuss other style-specific aspects, but in general, these findings adhere to outcomes I have found that point at style and alcohol content as being a driving force in perceptions of quality and ratings.

As the American beer industry has grown and matured, another addition to this segment has been sour/wild and saisons. These styles of are particular interest in this case not for their alcohol content, but specifically their rarity. Because of the time (sometimes years) and effort (high cost) to create these beers, it gained my attention while compiling my annual analysis of "best" beer lists. As noted in a follow-up post on the topic, the inclusion of one-off creations made from barrels or unique processes took a step forward in 2016:

This example is worth noting because of its impact on "tastemakers" within the industry, many who had best beer lists that contributed to my collection. And, as shown in recent research published in the Journal of Wine Economics, "...experts' ratings have both a statistically and practically significant impact on prices after controlling for the effects of other known detriments of price. Thus, expert opinion has significant value in this setting."

Given what we know about price and assumption of quality, it may be relevant to consider Robert Ashton's research as it pertains to beer. As he points out in "The Value of Expert Opinion in the Pricing of Bordeaux Wine Futures," the positive ratings of two prominent wine critics, Robert Parker and Jancis Robinson, can directly influence price, and therefore perception of quality. If that is the case, it would do us well to consider how ratings from prominent beer magazines, personalities, and even rating websites could do the same. It might be safe to assume that the future inclusion of barrel-aged sour/wild and saisons among "best" beers created in the U.S. is already secured, thanks to the slew of characteristics that align with what makes a rare beer a quality one and the time and attention required to make those styles.

The results from reviewers and tastemakers may only reach (and influence) a small percentage of the beer drinking population, but this is also the group from which trends are solidified or sometimes created. Plus, we know that any kind of expertise has potential to impact behavior and assumption of quality. A key takeaway from Ashton's work: expert opinions may not necessarily mean the opinions are valid - taste is subjective - but they are valid by social-psychological standards previously discussed, "which maintains that expertise is socially conferred by constituencies that rely on analyses and opinions provided by the deemed experts," he writes.

Which puts beer in an interesting spot. Not only do industry tastemakers matter in terms of bias and preference that might influence others, but they're impacted by the psychological cues that make rare beers so good in the first place. Ratings and decisions are based on quality, but there is more to the final score. On top of that, the social nature of beer and an increasing value placed on online interactions means that more people can become an "expert," or, at least, an influencer. When considering the sum of research presented so far, all this comes back to the power that authenticity - and rarity - wields over us.

"... from a product marketing perspective, a unique product is one that is highly differentiated from all other products in its category. Such differentiation is known to be essential to product and brand success, because it both minimises direct competition and the likelihood that any other product can serve as a suitable substitute," a team of New Zealand researchers wrote in a 2016 paper for Food Quality and Preference.

Price and access have proven to have the ability to impact assumptions and perceptions of quality, but increasingly, factors of "uniqueness" and authenticity rise to the top. As we consider what this means for beer moving forward, we should try to be more cognizant of how our perceptions of quality are affected.

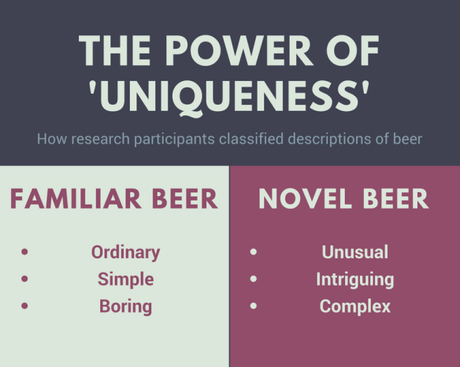

For example, by testing participants with collections of beers that would be classified as "familiar" versus "non-familiar," a team at The New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research found, "...beers classified as 'familiar' were highly correlated with responses to descriptive statements that they were 'ordinary', 'simple', and 'boring' beers, while those classified as 'novel' were correlated with statements that they were 'unusual', 'intriguing' and 'complex' beers."

Liking or disliking beers, they discovered, had to do with "how familiar or novel they are to the consumer." Sound familiar? Even more to the point, "novelty and complexity are associated with high levels of arousal."

One caveat that is offered by the research, however, is that the appeal of beers is more complex than just familiarity. Situation and setting, for example, also play a role. But given what we know about the social aspects of rarity and its own influence, along with previous highlights of price, production levels and authenticity, these may be the missing pieces to complete the puzzle. American drinkers are seeking aspects of authenticity, found through craft beer.

The phenomena we see in relation to these characteristics have been shown across multiple countries, drinking cultures and types of alcohol. To find connections through all suggests the psychological and sociological effects of authenticity and rarity have a universal ability to impact us.

Does this mean we have road map to create a successful brewery or beer? I wouldn't go that far, but the framework offered through this collection of data and academic research feels compelling enough that areas of brewing, marketing and branding can overlap to create something powerful or useful.

None of this may be wholly groundbreaking to our collective anecdotal experience and findings from a variety of other luxury goods, but with every new brewery that comes online and every piece of data we can collect - from ratings to narrative stories - we find ourselves smarter and more understanding about what's going on, and, in a way, what's at stake.

Searching for good beer takes us to all sorts of places, whether digital, physical or emotional. Perhaps it's also making us think subconsciously about what that means, too.

Bryan Roth

"Don't drink to get drunk. Drink to enjoy life." - Jack Kerouac