And Now, For Your Listening Pleasure…

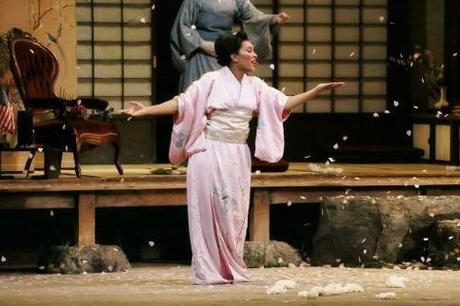

Cio-Cio-San (Talise Trevigne) & Suzuki (Lindsey Ammann) in Act II of Madama Butterfly (Photo: Curtis Brown)

Cio-Cio-San (Talise Trevigne) & Suzuki (Lindsey Ammann) in Act II of Madama Butterfly (Photo: Curtis Brown)

Interestingly, North Carolina Opera’s November 1st presentation of Madama Butterfly was given in two acts, with the second act divided into two parts bridged by Cio-Cio-San’s night vigil, which includes the exquisite “Humming Chorus” and the orchestral Intermezzo. For all intents and purposes, this should be the preferred method of presenting the work, which as we know was the way Puccini originally envisioned his favorite opera to be given.

That said, most opera company’s continue to stage the work with two intermissions, separating the piece into three distinct acts, but at the same time trying to respect the composer’s wishes by consciously reminding spectators that Act II is really in two parts. However it’s done, either way will work, the point being that audiences will flock to the opera no matter how it’s partitioned, as long as the lead roles are performed to the best of the artists’ abilities.

On that count, audiences in Raleigh had nothing to fear. NCO’s Artistic and Music Director, Timothy Myers, led a most revelatory reading of Puccini’s score, surely one of the composer’s most elaborately conceived creations in terms of exoticism, local ambiance and, despite the Japanese setting, quintessentially Italianate passion.

From the opening fugato to the final crashing chords, Myers was in firm command of his forces, displaying commitment and drive in conveying the primary colors of this gorgeous piece. His leadership kept the sometimes stagnant stage pictures from straying off into dull routine.

I cannot praise his efforts enough, which I first spotted with his excellent stewardship of NCO’s Don Giovanni in April. His best moments came during the dream-like night vigil and especially the affecting Intermezzo, one of Puccini’s most descriptive symphonic tone poems. The Intermezzo foreshadows Pinkerton’s return, a projection of Cio-Cio-San’s anticipation of her husband’s homecoming.

Tempos throughout were generally on the brisk side, but not so fast as to be rushed. For the depiction of dawn over Nagasaki Bay, Myers coaxed some lovely sounds from the string and woodwind sections, which made equally telling points during the marriage broker Goro’s introduction of the three servants at the start of Act I.

While the Intermezzo played in the pit, my mind wandered to inevitable comparisons with Claude Debussy’s La Mer, which Puccini must have known and surely been influenced by. This piece’s sweeping impressionistic harmonies contrasted vividly with the Tuscan composer’s more melancholy strains, which Myers dotingly brought out for our enjoyment. Overall, there wasn’t a moment of slackness anywhere in his leadership, a major accomplishment in itself.

Myers is to be commended for a performance worthy of truly illustrious predecessors, among them Arturo Toscanini, Oliviero de Fabritiis (who presided over the classic rendition of the opera with Dal Monte and Gigli), Tullio Serafin, Sir John Barbirolli, and the late Lorin Maazel. Myers’ guidance could also be felt in the singing, which was uniformly excellent in just about every role.

About the only things I missed were the backstage anchor noises (called for in the libretto) to supplement the sailor’s calls as Pinkerton’s ship, the Abraham Lincoln, pulls into port. In spite of that minor lapse, maestro Myers steered the proceedings in exactly the right direction: all eyes were fixed on the stage where they belonged, while our ears made note of the superb musical accompaniment provided by the versatile NCO Orchestra. Under Myers, the music ebbed and flowed as few verismo scores of the period did.

The staging of the night vigil was preceded by the Flower Duet (so reminiscent of Delibes’ similar pairing in Lakmé, as previously noted), which featured a shower of petals tossed onto the stage from the overhead catwalk. I would have welcomed a more restrained hand in tossing out the petals. However, it did conjure up visions of La Bohème when, in Act III, snowflakes appear to fall on Rodolfo and Mimì as the couple agrees to part in the spring. It’s my opinion that Butterfly is the natural offshoot of La Bohème, while La Fanciulla del West is basically a Tosca retread. Both Butterfly and Fanciulla profited from the melodic advances of the pentatonic and whole-tone scales that Puccini borrowed from oriental influences and from Debussy.

Butterfly Emerges from Her Chrysalis

In the title role, soprano Talise Trevigne had the toughest assignment and the biggest shoes to fill. Cio-Cio-San has been performed by a wide variety of vocal categories: from light coloratura (Toti dal Monte) and heavier lyric (Anna Moffo, Renata Scotto and Mirella Freni), to full-blown dramatic (Maria Callas) and lirico spinto (Renata Tebaldi, Antonietta Stella, Leontyne Price, Martina Arroyo and Leona Mitchell).

The projection of a smaller voice into a large auditorium, and over a full orchestra, are the main obstacles to overcome. This is what ultimately prevented Brazilian light soprano Bidu Sayão from undertaking this strenuous part, one she had long wanted to sing. For the artist who possesses a more potent instrument, the issue involves scaling down the voice so as not to overpower the other artists. We are, after all, talking about a fifteen-year-old girl. And in order to make her sound credible and lend believability to her character, a bit of vocal sleight-of-hand is called for.

Physical appearance counts for much, although Cio-Cio-San’s Japanese ancestry can be hinted at through makeup, carriage, bearing, hairstyle and gestures — in short, all significant aspects of, and tailored specifically to, her samurai lineage.

Ms. Trevigne, while sounding subdued and soft-grained at the outset, slowly but confidently eased into the part as Butterfly’s dilemma began to unfold in subsequent scenes — so much so that by the middle of Act II, I was won over by the singer’s straightforward manner. Talise gave the impression of childlike innocence, tempered with a growing maturity brought on by the troublesome nature of her position as the abandoned wife of an American naval officer.

Her fending off of the annoying Prince Yamadori was humorously handled and elicited chuckles from the audience for her cheek in confronting the haughty aristocrat. Vocally, Trevigne opened up marvelously in the central portions of Act II, which, in the words of tenor Richard Tucker, is the true test of a Butterfly. Earlier, her probing account of the searing solo “Un bel di,” despite excellent delivery, felt tentative, a sensation I had picked up from Act I, where Talise employed a “little girl” demeanor. I feared for her vocal security at this juncture, thinking of the rigors to come and the dramatic demands this role places on the performer.

On that score, my fears were unfounded. Talise traversed every hurdle called for in the score. For a coloratura, she displayed ample power when called for, in particular her dismissal of the American Consul Sharpless after he advises her to accept Yamadori’s proposal of marriage. Greatly offended, Cio-Cio-San shows him the door in a scene of intense anguish. Both Trevigne and Michael Sumuel as Sharpless stayed “in character” and timed each other’s reactions to the needs of the moment. Along with the entirety of Act II, their exchanges during the letter reading were the highlights of the show.

At the end, Ms. Trevigne was the only singer who received a standing ovation from the crowd. When maestro Myers came out for his bow, the soprano greeted him with a generous hug. This told me all I needed to know about who was responsible for the preparation and coaching of this grueling assignment.

Another example of her mastery of the part came with Cio-Cio-San’s farewell and suicide. In the poignant “Piccolo Iddio,” Trevigne expressed an abundance of pathos, but dialed down the mawkish aspects in order to make the final scene that much more gripping. Her voice poured forth torrents of sound, all of them specifically tailored to the drama — again, surprising for a coloratura whose previous assignments included Ophélie in Thomas’ Hamlet, Mimì in La Bohème, and encounters with Mozart’s Susanna from The Marriage of Figaro and Pamina in The Mozart Flute.

The Rest is Pure Gold

But for some issues early in Act I, due mostly to faulty intonation, Michael Brandenburg’s Pinkerton was exceptionally well sung. He coped valiantly with the high tessitura, hitting and sustaining all those A’s and B’s in his melodious exchanges with Sharpless, as well as those bountiful B flats in “Amore o grillo” and a ringing, full-voiced high C at the climax of the love duet.

On the whole, Brandenburg proved his mettle as an actor. His genuine Yankee swagger at “Dovunque al mondo,” was palpable, as was his diffidence in disregarding Sharpless’ concern about his impending marriage to Cio-Cio-San. This Pinkerton was ready for action from the get go. Brandenburg’s lyric voice blended beautifully with those of the other singers, including a more than satisfying Goro and a remarkably personable Sharpless — more about their individual contributions in a moment.

Continuing, the Indiana tenor’s handling of Pinkerton’s swelling vocal lines lent plausibility to his bride’s belief that here stood the man of her dreams. He was gentleness personified at the phrase, “Bimba, bimba non piangere,” imploring his young bride not to weep after being cursed by her uncle, the Bonze, and her disapproving relatives. And he melted all hearts with his bold entreaties of “Vieni, vieni,” later in their duet.

During the wedding scene, although he made light of Butterfly’s relatives, Brandenburg never overstepped the boundaries of decency. Tossing one of her puppet ancestors into the air, he sensed his bride’s discomfort at this apparent act of disrespect, which he quickly covered up. This was done in the most natural manner possible, a refreshing departure from past portrayals of the American naval officer as an S.O.B.

I was more troubled by the boos he received at his curtain call, which (I am told) had mostly to do with the caddish nature of his character than with his fine singing. In that regard, this is a young man on the rise who bears watching.

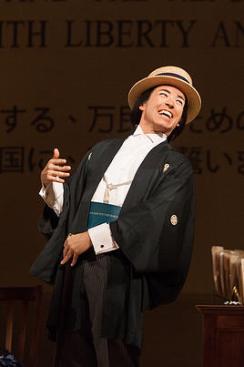

Tenor Ian McEuen was an outstanding Goro. He really sang the role, which was another unexpected surprise. Goro normally comes across in most productions as a busybody, the verismo incarnation of Wagner’s Mime from Siegfried: a whining, scheming, sniveling gnome-like creature of little to no scruples. But in McEuen’s expert hands, a satisfying portrait of the greedy marriage broker emerged. The tenor’s warm voice wrapped itself around his character’s music like a velvet glove, which was most welcome.

Uncharacteristically, Puccini gave this “minor” player some of his most delectable tunes, something he would only deign to do some 20 years later for the Trio of the Masks in his brilliant scoring for the incomplete Turandot.

I have only one objection, and that is with Goro’s reappearance towards the end of the opera, where he listened in on the maid Suzuki and Kate Pinkerton’s conversation. This was uncalled for and not at all required of the story. When Cio-Cio-San dismisses him in Act II for his meddling and spreading rumors about Pinkerton’s desertion (“Va via!”), it is assumed he is no longer welcome in her household. For Goro to lose face by sneaking back and risk being seen by others goes against the very grain of Japanese custom. If I were the director, I would seriously reconsider this aspect.

Michael Sumuel’s beautifully modulated and excellently articulated Sharpless was a delight throughout. His was the most consistently sympathetic portrayal, with marvelously shaped phrasing and deftly placed delivery, a superbly realized assumption by his amazingly pliable but no less talented bass-baritone. His American Consul was deeply felt and completely in tune with this character’s struggles to convince Butterfly of her situation.

Not only did Sumuel contribute to the dramatic arc of Act II, he sparked real interest in the ensuing dialog between Sharpless and Pinkerton. Like Goro above, their scene is usually treated in matter-of-fact fashion, with conductors neglecting to take full advantage of the gorgeous tenor-baritone writing Puccini has provided. For this, we have maestro Myers to thank. It’s at times like these, with a performer such as Mr. Sumuel, who is so in tune with the composer’s intent, that one laments the loss of Sharpless’ Act II aria, which Puccini cut prior to the La Scala premiere.

Lindsey Ammann’s Suzuki displayed a rich mezzo-soprano voice. This was luxury casting for this role. She, too, elicited much empathy as Butterfly’s loyal maidservant and only companion. Her Wagnerian sized instrument filled the auditorium with her cries lamenting Cio-Cio-San’s sad fate. Ammann has previously sung in the Metropolitan Opera’s Ring cycle production by Robert Lepage, during the 2010-2011 run of the work, as well as at Stuttgart Opera as Mary in The Flying Dutchman. A talent to watch!

As Yamadori, baritone Jesse Malgieri also drew a real flesh-and-blood individual out of this bland, self-serving and self-satisfied fop. Previously, Malgieri appeared with North Carolina Opera in Verdi’s La Traviata. Both he and conductor Myers shared a close association with Lorin Maazel, whose Decca/London recording of Traviata is a particular favorite of mine.

The Bonze was performed by Chinese bass Wei Wu, whose formidable physical size and booming voice brought a terrifying presence to Butterfly’s priestly uncle. One perceptive bit of stage business involved the Bonze’s close proximity to Pinkerton, where these two characters exchanged harsh glances at each other — a most effective moment and one endemic to the clash of cultures present in the work.

Others in the cast included mezzo Kate Farrar as Kate Pinkerton, given more to do in this production than most singers have in the past, Charles Hyland as a clear-voiced Imperial Commissioner, Tom Keefe as the Registrar, Jacob Kato as Uncle Yakuside, Austenne Grey as the Cousin, Annette Stowe as Butterfly’s mother, Margaret Maytan as the aunt, and Ella Fox as Butterfly’s son Sorrow (“Dolore” in Italian, but originally called “Trouble” in the Belasco play).

The lighting designer was Mark McCullough, who could have spotlighted the performers — and some of the front-stage action — a bit better. The chorus master was Scott MacLeod, and the costume coordinator was Sondra Nottingham. Scenery was designed by David P. Gordon for the Sarasota Opera. It was constructed and painted by Center Line Studios, Cornwall, NY. The scenic backdrop was the work of Michael Hagen, Inc., of South Glens Falls, NY. The costumes were designed for the Utah Symphony and Opera by Alice Bristow. The men’s wardrobe was apt and strictly of the period (Japan, ca. 1900), while the women’s kimonos radiated authenticity without descending into parody or a road-show rip-off of The Mikado.

The opera was directed by E. Loren Meeker, who has previously worked with Washington National Opera on Carmen, Lyric Opera of Chicago on Die Fledermaus, Houston Grand Opera on Trial By Jury, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires on Manon, and the Sand Diego Opera on La Bohème. As indicated above, more spotlighting of the principals might have helped to position the players better and clarify their relationships to one another.

One major faux pas that this version and far too many Madama Butterfly productions overlook is permitting the performers to enter a Japanese home without removing their footwear. Even as humble a dwelling as Cio-Cio-San’s tiny abode demands that this essential decorum be observed.

Honorable mention must go to that adorable tyke, Ella Fox, who played Sorrow. Most child actors tend to either hog the limelight or are more “trouble” than they’re worth. Not Ella. She behaved commendably in these surroundings, with poise and ease in her moments on stage. In addition, she helped to humanize the other participants in ways that only children can: by drawing such feelings as joy and tenderness out of grown adults. Brava, little diva!

Butterfly’s End and Puccini’s Passing

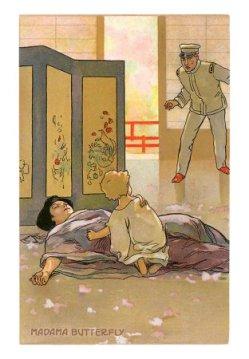

Cio-Cio-San completes her transition from young girl to mature woman by opera’s end. She achieves the stature of a tragic heroine with the realization that Pinkerton will never return; that her little son Sorrow will no longer be part of her life. My only qualm with the finale as staged by NCO — and this is strictly from my personal perspective, not a reflection on the positive facets of the production as a whole — involves the ritual surrounding Butterfly’s death.

In the original stage directions, Puccini indicated that Cio-Cio-San give her son a doll and an American flag to play with while he is blindfolded. She then goes behind a screen and plunges her father’s sword into her neck. (Historical note: only men and women of samurai descent were allowed to commit seppuku, which was part of the Bushido Code of Honor; the term hara-kiri was also used to describe ritual suicide in the form of disembowelment. Men tended to kill themselves by this method, sometimes followed by a second who completed the task with decapitation; while women most often placed a sword or dagger to the throat or neck).

In this production, the child is marched off to join Suzuki in the inner room. While Sorrow is there, Pinkerton cries out Butterfly’s name repeatedly (three times, to be exact) as Butterfly had indicated to Suzuki he would in “Un bel di.” But instead of killing herself at the crash of the gongs (as noted in the score), here she waits for Pinkerton’s last cry of her name before doing herself in. The opera ends with a repeat of the music that followed Cio-Cio-San’s words, “Morta, morta!” (“Death, death!”) from her later aria “Che tua madre.” It’s a gut-wrenching moment for any singer.

I’m all for originality in staging. And I have no objection to director Meeker for varying the formula of Butterfly’s death somewhat. I believe choices are made in the many discussions beforehand as to what needs to take place and why. Goodness knows any number of avant-garde artists have taken greater liberties with the text than were found in Meeker’s direction. Nevertheless, Puccini and his librettists were skilled men of the theater. They knew their craft and practiced it wholesale. They also knew what worked and what didn’t (or at least, they thought they knew).

Puccini, above all the verismo composers, traveled widely to oversee new productions and revivals of his work. He visited New York’s Metropolitan Opera on several occasions, in 1907 with the company premiere of Madama Butterfly and again, in 1910, with the gala premiere of La Fanciulla del West. Even after spending so many frustrating years in search of a subject and then having to put up with an infinite number of diversions, Puccini was still able to supervise the proceedings on a first-person basis. This in itself is quite extraordinary, that he took that much interest in his oeuvre that he would travel great distances to ensure their feasibility.

This extra degree of care which the composer demonstrated spoke volumes for how he wanted his works staged. Wagner left similar mandates, as did quite a few others. I wonder, then, what Puccini would have thought of these slight modifications to his carefully considered directions. Perhaps I am being needlessly picky or just plain obstinate. Yes, I admit that I am a traditionalist at heart, but I have enough of an open mind (especially where opera is concerned) to look dispassionately at a director’s work and accept that there are other points of view.

What we do know is that Puccini had been suffering from a throat ailment for some time — possibly two decades or more. If the known facts of his smoking habit are correct, he was mainly a two-to-three pack a day smoker. In his youth, this habit did not prevent him from work; in his later years, however, it tended to slow him down markedly, more so than the diabetes that was detected after his 1903 auto accident.

By the time of Turandot, around the end of October 1924, Puccini was suffering such excruciating pain that he reluctantly agreed to consult with various throat specialists (some without his family’s knowledge) in order to seek relief. One specialist suggested he receive the then-revolutionary and highly experimental radium therapy treatment at the Ledoux clinic in Brussels, Belgium.

While in the city, and before his treatment began, Puccini had gone to the Téâtre de la Monnaie to see a performance of Madama Butterfly. This would be the last piece of music Puccini would ever hear. That it turned out to be his favorite of all his works proved prophetic. According to several accounts of the composer’s last days, on November 24, 1924, seven radium tipped needles were inserted into an aperture in his throat. They were positioned as to destroy a tumor that had been welling up for some time. Because of his weakened condition, Puccini was given only a local anesthetic.

While outwardly successful in diminishing the tumor’s size, a few days later, on the afternoon of November 28, Puccini was said to have collapsed in his chair, his heart having given out due to the strain of the operation. He died a day later, on November 29, 1924, at 4:00 a.m. in the morning.

The ironic twist of fate that led to Puccini’s untimely demise can be seen in Butterfly’s tragic death by suicide. In the samurai tradition, Butterfly had pierced her throat with her father’s sword. Puccini, whether it was known to him at the time, had his throat pierced not by a sword, but by seven needles — one each for the seven operatic works on which the composer’s fame rests today.

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes