Will you accept of the key of my heart

To bind us together and to never never part?

Madam, will you walk?

Madam, will you talk with me?No, I won’t accept of the key of your heart

To bind us together and to never never part.

Neither will I walk,

Neither will I talk with you.(Traditional English song)

BBC Radio 4 has just broadcast a dramatisation by Marcy Kahan of Mary Stewart’s first novel, Madam, Will You Talk?, and it has reminded me how much I enjoyed her books and why. Stewart is often credited with inventing the romantic suspense genre, and by the 1960s was one of the top three woman writers in the world, selling 25 million copies of her ten novels. Recently she was the subject for our Reading 1900-1950 groups, and although I re-read Wildfire at Midnight (1956) then, I never got round to a review. I came across Stewart’s novels when I was about 14, recommended by my English teacher, and I have a couple of paperbacks from then. Now I’ve re-read Madam, Will You Talk? and reflected on what I took from Mary Stewart when I was a teenager, and what I take now.

There is always Stewart’s skill as a storyteller. She conjures satisfying plots, usually set in exotic foreign locations. A young woman, often alone in the world and unhappy, seizes an opportunity, takes a chance, changes direction. But her new course is not smooth. She faces a mystery, someone or something missing, perhaps a murder. While sex is offstage, there are always a couple of men around, strong-minded and naturally attractive in a ‘damn your eyes’ way, one of whom will be unmasked as the hero, in time for a happy ending. It is of course a riff on Cinderella or Jane Eyre. Mystery and romance expertly mixed.

If it sounds formulaic and dated, well, yes, perhaps. There’s a good deal of smoking too, for this is the 1950s. But don’t dismiss Mary Stewart. She was writing romantic suspense earlier than most, and doing it better. Such is her gift that you are swept up and along.

You might think that this is not really enough to keep the novels in print today, but there is more.

Somewhat surprisingly for the period, her female protagonists are independent, strong and resourceful. By the end of the novels, they may well be heading happily for conventional marriage, but essentially on equal terms with their men. They accept responsibility, they stand up for themselves and others and they don’t give up. When Vanessa March in Airs Above the Ground (1965) learns that her husband is not in Stockholm, but in Vienna, possibly with another woman, she sets off for Austria at once. The Ivy Tree (1961) sees Mary Gray, working in a dead-end job, agree to take someone’s place for financial gain. In Madam, Will You Talk?, Charity Selborne is a widow, on holiday and realising she is drifting. Tempered by the recent war, which lurks in several Stewart novels, she does not hesitate to protect a young boy pursued by the violent father he fears.

… some of the loneliness of the child’s situation dawned on me, and made me feel chilled. I knew a lot about loneliness. And I knew that, come murderers, come hell, come high water, I should have to do something about it. (Chapter 3)

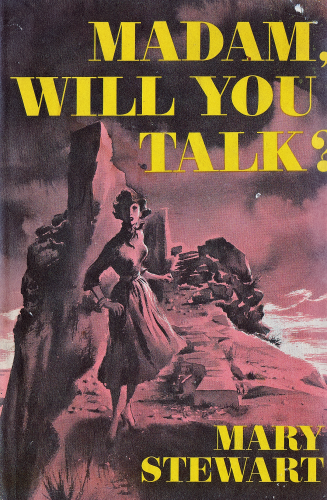

An appalling paperback cover, showing a not very independent heroine in an awful frock. As often, Stewart fell victim to romantic designs

A particular pleasure is the setting of Stewart’s novels. She once said:

I always start with the place and it suggests to me the kind of story, and l throw in the sort of people I know, and their reactions to what happens shapes the book. It may sound as if there is a set formula, but although similar elements are there, the atmosphere of the place, and therefore the approach, is quite different. (Birmingham Daily Post, 26 February 1969)

Only one of the early stories takes place in Britain, and even then it is on remote Skye. No, the gray and shabby country, struggling to recover from the war and short still of money and food, is left behind. Readers are bathed in the warmth and light of the Mediterranean countries. Madam, Will You Talk? came from a holiday Stewart and a friend took in Provence, with Charity and other characters visiting, or being chased through, Avignon, Les Baux, Marseille and the countryside around.

The road was a white and powdery ribbon that twisted between slopes of rock and scrub. Whin I recognized, and juniper, but most of the shrubs were unfamiliar – dark green foliage that sucked a precarious life from the cracks among the screes and faces of white rock. Here and there houses crouched under the heat, clinging to the edge of the road as if to a life-line; occasionally a grove of olives hung on the slopes like a silver-green cloud, or a barrier of cypress reared its bravery in the path of the mistral, but for the most part the hot and desert slopes rose, waterless and unclothed by any softer green than that of gorse and scrub. (Chapter 4)

The Pont d’Avignon, the Palais des Papes, the Pont du Gard and ruined hilltop castles offer romantic colour, and there are lively cafés, restaurants, markets a-plenty.

Avignon is a walled city … a compact and lovely little town skirted to the north and west by the Rhône and circled completely by medieval ramparts, none the less lovely, to my inexpert eye, for having been heavily restored in the nineteenth century. The city is dominated from the north by the Rocher des Doms, a steep mass of white rock crowned by the cathedral of Notre Dame, and green with singing pines. Beside the cathedral, taking the light above the town, is the golden stone palace of the Popes. (Chapter 2)

This must have been almost beyond imagining for many readers in the early 1950s. Cheap, easy air travel did not exist and, for most people, foreign holidays were simply unknown and foreign cuisine untasted. When I came to Mary Stewart, it was years after post-war austerity but I had not traveled much and her descriptions mesmerised me.

… there grew in me that show sense of exhilaration which one inevitably gets in a Southern town after dark. The shop windows glittered and flashed with every conceivable luxury that the mind of the tourist could imagine; the neon lights slid along satin and drowned themselves in velvet and danced over perfume and jewels … (Chapter 2)

The dinner that I had dreamed up proved to be every bit as good as the dream. We began with iced melon, which was followed by the famous brandade truffée, a delicious concoction of fish cooked with truffles. We could quite contentedly have stopped there, but the next course – some small bird like a quail, simmered in wine and served on a bed of green grapes – would have tempted an anchorite to break his penance. Then crêpes Suzette, and finally, coffee and armagnac. (Chapter 7)

Worthy of special mention, I think, is Mary Stewart’s interest in clothes. Her heroines generally have that elusive chic. Madam, Will You Talk? was written when fashion had finally shaken off wartime constraints. Rationed clothes and the wartime Utility line had ended, and Dior’s New Look, unveiled in the late 1940s, swept all before it (including the tone-deaf British government which condemned its extravagance). Glamour was back. It is not surprising that Charity Selborne is conscious of other women’s appearance:

She was, I guessed, thirty-five. She was also blonde, tall, and quite the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. The simple cream dress she wore must have been one of Dior’s favorite dreams, and the bill for it her husband’s nightmare. Being a woman myself, I naturally saw the enormous sapphire on her left hand almost before I saw her. (Chapter 1)

Charity’s own clothes are described too, and as she has money, we can assume they are high end.

The shadows under my eyes were still there, and so were the marks on my wrist, but I put on my coffee-cream linen dress and my silver bracelet, and felt pretty well able to face what might come. (Chapter 8)

We learn that Charity has also packed: a white frock with a wide blue belt, a pale green frock, a Mexican print frock and a dark coat. She has a make-up bag too:

I smoothed the rouge faintly over my cheek-bones, back towards the hair line, then dusted with powder. That was better. My coral lipstick next, and the face that looked back at me was an altogether braver affair. Thank God for cosmetics, I thought, as I put them into my bag; one not only looks better, one feels better, with one’s flag at the top of the mast again. (Chapter 7)

The young me delighted in all this style and, swathed in my hideous school uniform, longed to be soignée (a word I may have learnt from Mary Stewart). Now I have a much larger wardrobe, but I still admire the clothes of Stewart’s women. ‘No one can face a crisis unless they’re suitably clad.’ (Chapter 28).

It’s not all about the window dressing. Mary Stewart writes well, much better than most of her imitators.

But presently, round a curve in the city wall, the old bridge of the song came into view, its four remaining arches soaring out across the green water to break off, as it were, in midleap, suspended half-way across the Rhône. Down into the deep jade water glimmered the drowned-gold reflection of the chapel of St. Nicholas, which guards the second arch. Here, held by a spit of sand, the water is still, rich with the glowing colours of stone and shadow and dipping boughs, but beyond the sand-bank the slender bridge thrusts out across a tearing torrent. Standing there, you remember suddenly that this is one of the great rivers of Europe. Without sound or foam, smooth and incredibly rapid, it sucks its enormous way south to the Mediterranean, here green as serpentine, there eddying to aquamarine, but everywhere hard in color as a stone. (Chapter 3)

She is erudite too: her prose is filled with quotations and cultural references which at their best add to the story. Occasionally, as George Simmers has noted here, the English Literature graduate who taught in girls’ schools eclipses the storyteller. In the first chapter of Madam, Will You Talk?, we encounter Shakespeare, Dante, Lewis Carroll, Kipling, Chinese art, Norse mythology, French nursery rhymes, the Romantic poets and Ancient Rome. (And I may have missed others.)

Stewart wrote five novels in the 1950s, and another five in the 1960s. The later ones, though enjoyable, are less successful, I think, and perhaps Stewart was less comfortable with the 1960s and the thrillers ceased. There was one novel in the 1970s and then a couple in the late 1980s and 1990s, but the final novels include a magical element which somehow disturbs that balance of suspense and romance. The interest in magic is, by the way, given full rein in Stewart’s Arthurian trilogy centred on Merlin, published in the 1970s, and although I did at one time research Arthurian romance, the trilogy leaves me unmoved.

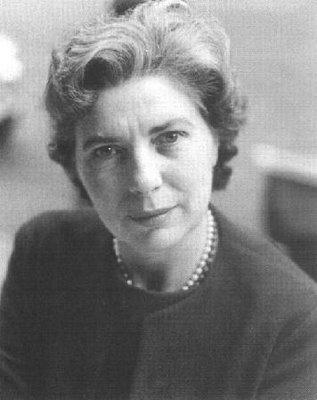

Mary Stewart

It is the early novels, like Madam, Will You Talk?, that I liked as a teenager and that I return to now. Much older, I thrill less to the mystery and romance. My pleasure lies in the sophisticated society of the novels, with its culture and beauty, elegance and style, but not so glamorous that I cannot, with a little effort, imagine myself there, clad in a pink linen frock and kitten heels, hair and nails done, sipping a cool drink on a hotel terrace. I know, of course, that the post-war 1950s world was in many ways narrow, poor, unequal, deferential, conservative. But, as described by Mary Stewart, it remains a place to visit occasionally, for old times’ sake.