Join us this Saturday, March 21st at 1:30 p.m. to see how costume design and artworks in the Luce Foundation Center connect to one another as part of our Luce Artist Talks. For March and April, the talks will be presented by artists associated with the Source Theater Festival, which is organized annually by CulturalD.C.. Luce Artist Talks are presented in collaboration with CulturalDC.

Deb Sivigny is a costume and scenic designer based in Washington, D.C. She collaborates with other designers to create worlds through her costumes and scenic design for numerous shows in the D.C. area. She did the scenic design for plays presented at the Source Festival in 2013 and 2014. Recently, Gloria Kenyon, a program assistant in the Luce Center, sat down with Deb to talk about her design process and its connection to other visual arts.

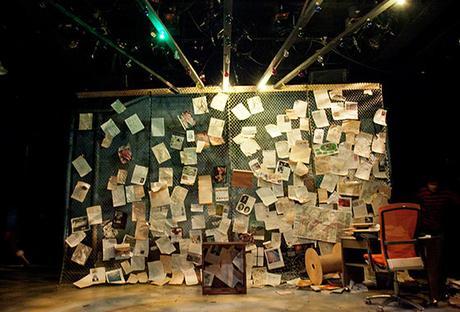

One of three iterations of the 2013 Source Festival's production of A Frontier, As Told by the Frontier by Jason Gray Platt, directed by Lee Liebeskind, scenic design by Deb Sivigny

Eye Level: How did you become interested in costume design?

Deb Sivigny: I've been sewing clothes since I was nine, and while it was fun to put together looks, I wasn't any kind of fashionista. I enjoyed the more technical aspects of the work—the engineering, the way pieces fit together. When I went to college, I was hired to work in the theater department's costume shop. As I was exposed to upperclassmen and professional costume designers I discovered that costume design combined history, art, society, psychology and fashion into one field. What else combines all those things? I started taking art history and drawing classes, theater design courses, and worked on every production I could get my hands on.

EL: Can you describe your design process and how you combine all the elements you mention?

DS: I tend to begin with the text, taking down major impressions, coming up with possible answers for the questions it poses, and then I head into a meeting with the director and design team. The director is responsible for getting us all "on the same page;" in my best collaborations, the team has shared research. After initial meetings, I [conduct] extensive research on the world of the play, gathering images of everything that inspires me from a silhouette and landscape to the shape of buttons and the turn of a table leg. I don't edit much in the initial research process—I'm looking for anything that gets my creativity flowing and reminds me of the character—whether the physical person or the essence of the space.

Eventually, I compile all the research for each character or place and get drawing. The drawing process allows me to funnel the research down to its most essential elements for each character or setting. The drawings are about communication, so they need to be clear. After designs get approved and presented to the team, my process then involves translating the drawing into sculpture via fabrics, understructure, and understanding the movement of clothes on a body.

That's really just the beginning; the process continues all the way through opening. I rely heavily on the input of my actors in rehearsals and fittings. They are the ones who inhabit these characters I've designed for and it's essential to me that they agree with and understand my choices. I am very collaborative. I don't like to work in a bubble.

EL: What types of visual art do you turn to for inspiration? Why?

DS: I love collage and assemblage because I love what the juxtaposition of elements and forms communicates. I tend towards works that have a tactile quality, whether that is a photograph of a stack of rusted metal or a wood plank so smooth you can see your reflection in it. I like anything unexpected, work that makes me say "huh", work that makes me laugh, or work that unsettles me. I am also really inspired by installation art and how quickly it can immerse you in a landscape. I try to emulate that feeling in my design work. I'm a bit obsessed with the work of Ai Weiwei and Choi Jeong Hwa lately—again, assemblage, repeated objects and forms and magic in the mundane.

EL: What relationships do you see between those types of art and your own work?

DS: There is something so visceral about seeing the work of the maker, whether that is the evidence of a blade or a brush or a needle. I enjoy folk art because it's often both utilitarian and aesthetically pleasing: a ewer for water with decorative ornaments, or a glass vase for branches. It's almost like folk art often asks for something from the natural world to finish it: flowers, a human, food... Garments also ask for a human to wear them. They are beautiful on their own but they are meant to be used and appreciated. I love seeing them in the museum setting though because they require more of my imagination to enjoy. It's not to say that paintings are passive, and I love anecdotes about painters in relation to their work, but my relationship to them is different.

EL: You describe your relationship to design as though it is both sedimentary rock and along a continuum. How do these two ideas—one of a stationary rock and one of continuous movement—work together to inform your design?

DS: Poetically, sedimentary rocks are created by tiny particles that have traveled from elsewhere to join them. They ultimately appear to our eyes in layered form, which reminds me that the particles that came before get compacted by the ones after. They're not erased, they just get embedded deeper in the rock. If the "rock" is me, the continuum is time. While I remain basically the same at the core, I learn with each production I undertake (taking on particles) and I carry that knowledge with me into the next project.