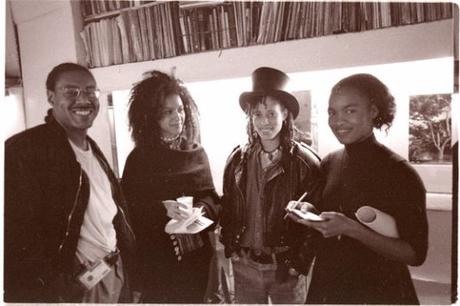

Michael Richards & Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian (Photo: Frank Stewart / The Studio Museum in Harlem)

Michael Richards & Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian (Photo: Frank Stewart / The Studio Museum in Harlem)The clock-radio went off at 7:45 a.m. on the morning of September 11, 2001, a radiantly sunlit Tuesday. Instead of being greeted by the usual reggae beat, a distant, far-away psalm in Latin verse came over the airwaves — softly at first, then stronger and more assured. Women’s voices predominated, followed by the men; an eerie sort of sound not much different from Gregorian chant that reverberated in a church-like atmosphere. It forced Michael Richards to pry open his eyes.

“Oh, Geez,” he muttered sleepily to himself, “what the heck is this?” Michael rolled over in his cot, a simple makeshift bed he’d been using with increasing frequency, while he stayed up till the “wee, small hours,” a close friend would say, working diligently on his art projects.

Despite being startled by the sound, the music was vaguely familiar, except that Michael had a hard time placing it. He chose to leave the radio on. It took some time for him to shake off the effects of the previous night’s indulgence. He had gone to bed late, long past midnight; it must have been two or three in the morning. No matter, Michael had to be up by 8:00 and on his way to the Bronx by 8:45. The subway ride from lower Manhattan took about an hour and twenty minutes on a good day, but it was less of a hassle than if he had made the trip from his home in Rosedale. Besides, he didn’t want to be late for work.

Work? Man, he thought, it wasn’t work at all. Not to him anyway. He loved his job at the Bronx Museum of the Arts. Michael was an assistant art laborer, sort of a go-to guy and artistic jack-of-all-trades. “Yeah, and master of none,” another wise-ass buddy once remarked.

“Hah, you’re probably right,” Michael would snap back, in that deliberately calm, non-confrontational style of his. He didn’t want to offend his pal, whom he had known since their Miami South Beach fellowship days. What’s the sense of it? He’d only seen him, what, three, maybe four times a day. Each and every day! “Why make enemies when you can keep the mutual admiration society going?” he reasoned. Good point.

“Damn! Why can’t I remember this tune?” There was something ethereal and slightly other-worldly about it. “Is this what they call an out-of-body experience,” he wondered. Moving in for a closer look, Michael noticed the radio wasn’t tuned to his favorite station.

“Yo, who’s been messing with my dial?” The call numbers read 96.3. This was WQXR-FM, a classical-music station. “Ah, right,” he remembered, with a look of bemusement. “Maybe Jeff had something to do with that.” Michael was referring to a fellow artist named Jeff, his studio neighbor and a die-hard football fanatic. The two of them had stayed up past their normal hour to watch Monday Night Football, which featured the season opener between the Giants and the Broncos at Denver’s Mile High Stadium. The Giants lost 31-20, a real heartbreaker.

Among other styles of music, Michael knew that Jeff liked classical. Michael, too, had wide-ranging tastes, but classical? A little gospel and blues perhaps, and, of course, lots and lots of reggae, a love of which he acquired while growing up in Kingston, Jamaica. Although Michael was born in Brooklyn — on August 2, 1963 — his father was a Jamaican by birth, one who had strong views about where his son should be brought up. His mother, a native of Costa Rica, had other ideas. Michael’s decision to become an artist and dedicate his life to art had initially been met with resistance by family members. Still, that did not stop him from pursuing his goal.

“Can’t dwell on that now,” he commented. “I got to get going!” With that, he turned off the radio, got up from the cot and went to the bathroom.

As he turned on the shower, Michael’s thoughts turned back to sports. It had rained the night before. “Man, it poured,” he added for emphasis. A passing thunderstorm that started before 7 p.m. blanketed the New York City skyline with threatening clouds. Heavy showers dumped nearly half an inch of rain onto Yankee Stadium, leaving a water-logged playing field in its wake. The game between the Bronx Bombers and the Oakland A’s, originally scheduled for later in the evening, had been scrapped. Michael was fond of baseball, but with the Yankee game cancelled football seemed the better option. Jeff thought so, too.

In as much as they both loved watching sports on television, Michael’s real passion was sculpture. He’d often work through the night on a piece, sometimes into the next morning — shaping it, defining it, tweaking it with his tools and hands, until in his gut he felt it was just right. “That Goldilocks thingee.”

Monday, September 10, had been an especially long day for him. He had come to the studio, located on the 92nd floor of Tower One (also known as the North Tower) of the World Trade Center, after having first attended a late afternoon opening at the Grey Art Gallery where he used to work, near New York University in Washington Square Park.

Returning from the gallery, Michael kept to his habit of working out in the gym, sculpting his solid six-foot-something frame into shape. Grunting and groaning, lifting multi-pound weights, working those leg muscles, flexing his arms, calves and thighs, and using the treadmill. He did this for the simplest of reasons: he needed his body for his projects.

Why would he, or anyone else for that matter, have subjected themselves to such torture? By covering himself with plaster resin and casting his own muscular build, Michael could put his time and effort to good use, as well as imprint his likeness on every piece he turned out — not unlike the carvings and statues of ancient kings and pharaohs.

Only, instead of relying on slaves to build 40-story-high tombs, Michael could depend on his friends and fellow artisans for help with the painstaking process. He worked patiently and methodically. Once the molding and casting were done Michael could manipulate the plaster resin to his desired purpose. In the age of advanced technology, his output was decidedly low-tech: therein lay its appeal.

On occasion, he would demonstrate to his girlfriend, now his fiancée, Christie, the labor-intensive process. She would stand there and gaze at him, admiringly, seeing how much he enjoyed the results of his labor. Keeping her in mind, he called Christie on his cell phone just after the football game had ended, to let her know he was still at work.

“Michael, it’s midnight,” she reminded him. “When can I see you?”

“Tomorrow, sweetie. I should be free by tomorrow, okay?”

Vanessa, Monika, Jeff, and the other 22 artists in the World Views program run by the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council — the entity that provided windowed studio space in Tower One — were also privy to Michael’s working methods, in particular his obsession with flight imagery.

It was an obsession that started about a decade ago. As a young black man, albeit one of distinctly Caribbean ancestry, living and working in the America of the new millennium, Michael took “the idea of flight” not only as it relates to his subsequent “use of pilots and planes, but” its references to “the black church, the idea of being lifted up, enraptured, or taken up to a safe place — to a better world,” as he explained it.

One of his earliest representations, from 1997, depicts a Tuskegee airman in flight suit, flight helmet and parachute. His eyes are closed, the body rigid and erect, with the hands flat against his side. Nails perforate the figure from the neck down to the lower abdomen and upper thighs. With the left leg bent slightly inward, it’s an obvious pharaonic pose preserved in fiberglass and resin with elements of iron oxide.

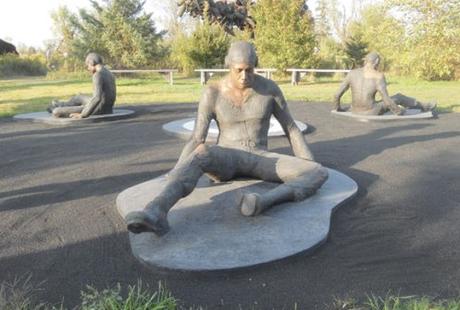

Michael’s continued use of “pilots and planes,” i.e., the famed all-black and segregated Tuskegee air squadron, came to full fruition in his year 2000 creation for the Franconia Sculpture Park, near the rural town of Shafer, Minnesota, entitled Are You Down? Originally made of glass fiber and resin, but recast in bronze in 2012 as part of a preservation project, this piece is a tableau of three downed air pilots positioned triangularly across from and with their backs to one another. Again, Michael was the model for each of the airmen.

In the middle of the structure is a large bulls-eye target which the figures have missed. The faces on the three airmen are downcast. According to writer, artist, designer and Twin Cities resident Glenn Gordon, “They speak not so much of the exhilaration of flight as of dreams of freedom crashed to Earth.”

A variation on this theme found its culmination in one of Michael’s two last surviving works. Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian is a bronze sculpture made in 1999 of a lone Tuskegee airman. True to form, the sculpture was cast from life, that is, from his own body. In this instance the airman is portrayed as the early Christian martyr St. Sebastian. But instead of the figure being pierced by multiple arrows, the artist, who is dressed once more in flight gear and accompanying helmet, is impaled by a horde of model airplanes.

Like his prior 1997 piece, Michael’s eyes are shut tight. But unlike that statue’s severe countenance, or the downed air pilots in Franconia, the face is tranquil and relaxed, the chin raised imperceptibly to the sky, the hands placed with their palms up in the manner of a supplicant. His feet, as indeed his entire body, are lifted off the ground by several inches. The structure is supported by a steel shaft, with the planes attached by steel bolts. The impression one receives is that of the pilot (or, if you will, Michael himself) ascending into heaven.

Michael recalled the artist’s statement he had composed back when Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian was completed — the statement he never had the chance to submit before his statue was exhibited at the Studio Museum in Harlem: “The Tuskegee airmen fought for democracy in the sky, but faced discrimination on the ground. They serve as symbols of failed transcendence and loss of faith escaping the pull of gravity, but always forced back to the ground, lost navigators always seeking home.”

Stepping out of the shower, Michael dried himself off and got dressed in his all-black outfit. “Say it loud,” he’d shout back at his reflection in the mirror, “I’m all in black and I’m oh-so proud.” He mused on his accomplishments to date, and was indeed proud of the fact that he was an artist-in-residence at several New York studios and museums; that he had had several gallery showings under his belt, among them the Chicago Cultural Center, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the aforementioned Studio Museum of Harlem, and the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh.

Even more than these, he was glad to have been able to address such issues as social injustice, discrimination, the lack of opportunity, racial intolerance and unfairness through his art. “I’m a credit to my race,” he pointed out half jokingly, in a paraphrase of sports columnist Jimmy Cannon’s famous observation about the boxer Joe Louis: “The human race!”

Looking at his watch, he still had a few minutes to think about his workload. One he was spending a good deal of time on had to do with a man riding a meteor. Another was a life-sized recreation of his torso with wings on its back. One of the wings was supposed to be broken off. He called this piece Fallen Angel. Michael gave out a little chuckle at that title. “Lucifer, you little devil, you’re the fallen angel!”

Time was getting short. Michael had to step on it if he was going to catch the subway train to the Bronx. Out of the blue, he found that he remembered the title of the choral music that had awakened him that morning. It was Adagio for Strings, sung by mixed choir in an arrangement by its composer, Samuel Barber. The words, based on the Latin text for “Lamb of God,” were part of the liturgy of the Catholic Church:

Agnus Dei

Qui tolis peccata mundi

Miserere nobis

Agnus Dei

Qui tolis peccata mundi

Dona nobis pacem

Lamb of God

You take away the sins of the world

Have mercy on us

Lamb of God

You take away the sins of the world

Grant us peace

This was something his Catholic friends would repeat when, on the rare occasion that Michael was invited to attend Mass, he would hear the priest speak these words from the altar: “Happy are those who are called to the supper of the lamb.” And the congregation would respond in turn: “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.” Even though he did not take communion, Michael invariably felt better afterwards. He especially looked forward to the sign of peace where the parishioners would shake one another’s hands.

It was 8:45, almost time to go. Michael had just enough time to turn on the TV and hear the latest weather forecast along with a summary of the previous day’s events. Satisfied, he turned off the set. Just then, he heard the ear-shattering noise of a jet engine, an unmistakable sound for someone, like himself, so attuned to aeronautics. In the next instant, an airplane crashed into Tower One between the 93rd and 99th floors. The time was 8:46 and thirty seconds.

Repeated calls to Michael’s cell phone went unanswered. In fact, no one’s cell phone was working properly that day, or the day after.

* * *

Michael Richards perished on the morning of September 11, 2001. He was 38 years and one month old. He was working in his studio on the 92nd floor of the World Trade Center Tower One, on the side facing the Statue of Liberty. Ironically, Michael was entombed with his work in a 110-story tower taller than any pyramid or obelisk from the ancient or modern world.

At exactly that same moment, fellow World Views artist Vanessa Lawrence had stepped off the 91st floor elevator when she felt the whole building shake. She headed for the stairs, making her way through smoke, debris and water. Eventually leaving the building, she saw that Tower Two had collapsed next door.

The above story is a fictionalized account of the events on the day of Michael’s passing. Though much of the dialog has been recreated, the events as they occurred are based on the written record and eyewitness accounts of those who knew the artist personally.

Linda Johnson Dougherty, chief curator and curator of Contemporary Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, was co-curator of the Defying Gravity: Contemporary Art and Flight Exhibit held in Raleigh from November 2, 2003 to March 7, 2004, as part of the Centennial of Flight Show honoring the Wright Brothers. It was during this exhibition that I first laid eyes on Michael Richard’s achievement, the mesmerizing Tar Baby vs. St. Sebastian.

But how did this particular piece become a part of the North Carolina Museum of Art’s permanent collection? Linda explained that the sculpture was a long sought-after item, but that it had not been among the artist’s work at the time of his death. Later, the museum learned that it was found stored inside a family member’s garage (that of a cousin who lived outside the city, in Mount Vernon). The family had given it to the museum as part of a long-term loan. It’s an incredibly moving and poignant piece, hugely significant and impressively displayed. The work is a commemoration of the artist’s life and talents and a memorial, of sorts, to those who died on 9/11.

Out of intuition and my own curiosity about the artist’s mind-set, I asked Linda if she felt Michael may have had a premonition of his own death. “No, of course not,” Linda insisted. “How could anyone know that? It would be impossible.” Indeed, one of the ironic coincidences of Michael Richards’ life was how his art transcended his manner of death. In a reference to this piece, Michael’s art dealer, Genaro Ambrosino, was quoted in the Associated Press as saying, “Although it was about death, it was more about liberation, freedom, being able to escape. It was a sad message because of what it meant historically … It was like redemption from all that.”

This lost navigator sought and found his home, a spiritual port of call. For it is only through Him, the above-named Lamb of God, that we can be redeemed.

When asked by a friend what he wanted out of life, Michael made this telling connection: “I want to live hard. I want to love hard. I want to work hard, and then I want to die.”

That he did.

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes