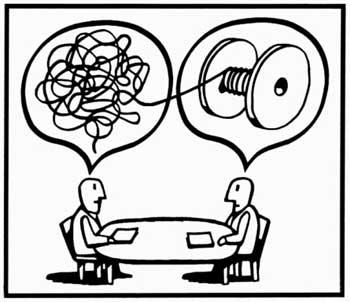

There is a sense in which we are all cultural narcissists. By this, I mean that because all of us are acculturated at a particular time and in a particular place, we have a strong tendency to view other times and places through our own cultural lens. These lenses are prismatic and what we see through them distorts.

I was reminded of this effect while reading an article about the “religious” beliefs and practices of a Scandinavian hunter-gatherer society, the Sami. The authors discuss these beliefs and practices using terms and concepts developed primarily in the context of Abrahamic religions. We are told that Sami “Religious practices included a variety of rituals and gestures connected to sacrifices. Offerings expressed veneration of the divine powers and established a relationship with the gods.” We also learn that the Sami worshiped a “sacred wooden idol,” which is considered to be a “deity” and tree carvings are “images of gods.” Elsewhere the authors talk about Sami “holy places.”

Sacrifice, divinity, god, holiness, and deity s0und suspiciously like Western rather than Sami constructs. Although we can trace these ideas back to the many polytheisms that first arose in Mesopotamia and then spread throughout the Mediterranean, they were systematically elaborated by the monotheistic traditions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. While it is possible that the Sami did in fact think and talk in these terms, there are several reasons for doubt.

The first comes from what might be considered naive or non-professional chronicling of native traditions. In most cases, our earliest knowledge of indigenous peoples comes from writings produced by explorers, traders, colonizers, and missionaries. They were not trained in ethnographic methods and inevitably recorded what they saw using concepts and language with which they were familiar. Our earliest accounts of indigenous people must be read with this in mind. The second doubt springs from the straightforward difficulties of language. Few of the earliest chroniclers were linguists and much was lost in translation. The third difficulty is the product of contact and diffusion. Ecumenical in their supernatural outlook, many indigenous peoples picked up on new ideas and incorporated them into their beliefs. Early chroniclers were often astonished to hear them talk about things that sounded suspiciously Christian, apparently without realizing that Christian ideas had long been in circulation.

Elsewhere in the article, we are told that Sami “religious beliefs were animistic, centered on animal ceremonialism.” While this seems simple enough, what does “animism” actually mean? I will confess to not having given this much thought until reading Nurit Bird-David’s superb history and analysis of the term. In “Animism Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology” (open access), she locates the origin of “animism” in E.B. Tylor’s Primitive Culture (1871) and sketches a genealogy of its deployment since that time.

For Tylor, animism was the attribution of life and personality to plants, animals, weather, and landscapes. He considered it to be a “primitive” trait that originated in dreams and thus was a form of error. Although most of Tylor’s ideas have been abandoned or substantially modified, Bird-David demonstrates that his thoughts on animism have been uncritically accepted and incorporated into the anthropological and historical mainstream. She convincingly shows that animism is an ossified and untroubled category that needs substantial revision.

For Bird-David, the anthropomorphism that characterizes animism is a form of relational epistemology and when viewed this way, it makes considerable sense. Because hunter-gatherers are profoundly and daily affected by plants, animals, weather, and landscapes, putting them into a personal or social relationship — one that is some ways negotiable — is a valid way of understanding and knowing the world.

Having intimate and life altering contact with plants, animals, weather, landscapes, and most importantly other people, hunter-gatherer epistemology does not begin with the individualistic and detached statement “I think, therefore I am.” This Cartesian construct, so deeply embedded (and essentialized) in Western thought, makes little sense to hunter-gatherers who consider relationships to be of paramount importance. Their first principle might thus be stated: “I relate, therefore I am.”

Animism is not, when considered this way, a simplistic or “primitive” way of knowing the world. It is a much richer (and more complex) idea that requires the careful use of concepts which differ from those used to construct the Western world.

References:

Bird-David, Nurit (1999). “Animism” Revisited: Personhood, Environment, and Relational Epistemology. Current Anthropology, 40 DOI: 10.1086/200061

Bergman, I., Ostlund, L., Zackrisson, O., & Liedgren, L. (2008). Varro Muorra: The Landscape Significance of Sami Sacred Wooden Objects and Sacrificial Altars. Ethnohistory, 55 (1), 1-28 DOI: 10.1215/00141801-2007-044