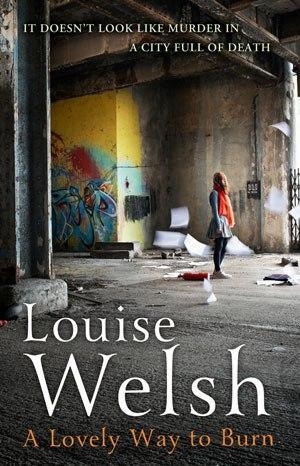

A Lovely Way to Burn, by Louise Welsh

The true test for any novel which is part of a series is whether the reader goes on to read the next in sequence. If they do then the novel succeeded. If they don’t then for that reader at least the novel failed.

A Lovely Way to Burn is the first of three thrillers each set against the backdrop of a pandemic laying waste to the UK and much of the world. The sequel’s already out and I plan to read it, so Burn succeeded for me. That’s worth bearing in mind given some of the criticisms of the novel I’m going to make below.

Stevie Flint is a presenter on a UK TV shopping channel. She’s the pretty and glamorous one, paired with an older woman named Joanie who adds a homely character to their show. Between them they flog tat to daytime TV viewers most of whom likely watch more for the company than the goods they buy.

Stevie’s boyfriend is attractive pediatric surgeon Simon Sharkey (he’s referred to as Dr Sharkey in the book, which is a minor error as in the UK surgeons are called Mr or Miss as appropriate). Simon’s handsome, rich and lives a fast-moving and high spending lifestyle. Stevie’s not sure if she’s in love with him, but she’s quite certain he’s fun to be around.

Before all that though the novel opens with for me a really misjudged prologue recounting three high-profile shootings that take place in London before the plot proper starts. Each of them is so dramatic that I genuinely think we’d still be discussing them decades later. An MP on a spree shooting; a hedge fund manager who goes berserk on the tube; a vicar who slaughters his congregation. Any of them would make international news.

The prologue doesn’t work because it’s incredible (unless of course an underlying connection gets explained in some later novel, but it’s still incredible now). I can buy a pandemic and I can buy a spree murder, but I struggle a bit with being asked to buy three spree murders and then a pandemic. Obviously the goal is to create a mood of tension and impending chaos, but it just flatly didn’t work for me and I think the novel would be better if the prologue were entirely deleted and the few subsequent references to it taken out.

After the prologue misfire we get into the plot proper. Stevie goes round to visit Simon only to discover him dead in bed, a victim of what she’s later told is sudden adult death syndrome. He died for no obvious reason but with no sign of foul play. Sometimes healthy people just die and however tragic it might be it’s not a police matter.

At about the same time a new disease nicknamed the Sweats has started going round and so far most people don’t realize quite how serious it is. Stevie goes down with it and her next few days are spent in a brutal and debilitating fever. She recovers, after which she’s visited by Simon’s sister who found a hidden letter at Simon’s flat addressed to Stevie. The letter leads to the discovery of a password-protected laptop hidden in his attic crawlspace and an instruction to take it to one of his colleagues and to trust nobody, absolutely nobody, else.

Here starts the mystery. If Simon’s death was natural, why did he leave hidden notes, stashed-away laptops and cryptic instructions just before it happened? Stevie goes to the colleague Simon named, but discovers that he’s come down with the Sweats too and unlike her he didn’t recover. Now Stevie has a dead boyfriend, a laptop that very quickly starts sparking interest from others at the hospital, and the disquieting possibility that Simon was murdered and that whoever was responsible might come after her next.

So far nothing so unusual, except that the Sweats continue to spread. At first most people assume it’s like having a bad cold and society continues on much as it ever has, just with more people off sick.

The Underground carriage’s fluorescence drained the passengers’ complexions of any luster. The dark skin of the business-suited man beside her had turned grey, and the woman leaning against the pole by the door had taken on a jaded sheen that reminded Stevie of the print of Tretchikoff’s green lady that had hung in her grandmother’s hallway.

Soon however it becomes apparent that almost everyone who catches it dies. Stevie’s immunity isn’t unique, but it is unusual. She still wants to find out why Simon died, but now her investigation is taking place in the midst of a new Great Plague.

‘What’s wrong with Joanie?’

‘The same thing that’s wrong with the rest of them, only more so, sickness, vomiting, diarrhoea, high fever, hot and cold sweats. Don’t you watch the news?’

‘I told you, I was sick. I thought it was the shock of finding Simon.’

‘The great washed and unwashed of London are going down with the lurgy, as are a good portion of Paris, New York and anywhere else you care to mention. People have died. That’s why I was going to send someone round to check on you. I was worried you might have shuffled off this mortal coil.’

For the first time Stevie thought she could detect a note of panic beneath Rachel’s posh bonhomie. She walked to the window. The parade of shops in the street below looked as busy as ever. Rachel had a reputation for exaggerating, but she wouldn’t lie about Joanie being in hospital.

Welsh says in her afterword that the book is in part inspired by classic TV dramas Threads and Survivors, both from the 1970s (the decade that optimism forgot). It shows because the best of the book is easily her portrait of London’s unravelling, slow for much of the book but then suddenly accelerating as the seriousness of the situation dawns and more and more people fall ill.

Less successful is the characterisation. Leaving aside that Stevie Flint and Simon Sharkey both seem to me very much names out of a thriller rather than real life, the characters here are pretty two-dimensional. Stevie is regularly asked why she’s risking her life investigating the death of a man she isn’t even sure she loved during what could potentially be the apocalypse and there’s never really a good reason for that. Nobody else is hugely developed either; people are largely what they seem and they’re painted in fairly broad brush strokes.

The flipside to that characterisation complaint is to ask what else I’d actually want. This is a conspiracy thriller. Subtle and nuanced characterisation would be rather beside the point. As a reader I need it to be clear who everyone is, what their role is in the plot and to be able to easily picture them and Welsh effortlessly meets every one of those criteria (save that I never quite worked out how old Simon was supposed to be, but he was dead so it didn’t much matter).

The trick to thrillers is cutting back on anything which gets in the way of pulling the reader on, to the next page and the next revelation. If character is too deep the reader will stop to explore it; if the prose is too beautiful the reader will slow down to parse and admire it; plot and atmosphere are key and language and character are there to efficiently carry the reader forward.

It’s true that I found the characters here a bit superficial and the language plain and it’s true that the plot didn’t hold too many surprises, but it’s also true that I enjoyed the book. I read though all 369 or so pages of Burn in a single day and as I said at the outset I plan to read both sequels (the first of which is already out). I just hope Welsh doesn’t take too long to finish the final book of the series.

Other reviews

Grant at 1streading put me on to this with his review here. I don’t normally link to newspaper reviews but this one from Leslie McDowell at The Scotsman picks up a brilliant point on the gender issues of the book which I missed. The key quote from the review is:

“As Stevie lurches from one dangerous situation to another, the image that is conjured up reminds one of US artist Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Stills, where a young woman is portrayed in various poses against a hostile city-scape. There are no women in Welsh’s dystopian world, apart from dead or dying ones. Technology is useless against the plague that is spreading and women have lost the power that technology once gave them. Simon’s medical colleagues are all male; one of them, Alexander Buchanan, even offers to send his son to collect Simon’s laptop from her. There are no daughters, no sisters, no mothers in this darkening world; as the city turns to chaos, men roam the streets and women become invisible.

…

By the end of the novel, Stevie has almost rid herself of her feminine look, marked at the beginning by her painted nails; she is wearing Simon’s clothes, has shaved her hair. The feminine has no place in a dangerous dystopian landscape. Perhaps that is what we should really fear.”

I think that’s a really impressive (and spot-on) analysis and I encourage anyone with any interest in this book at all to follow the link and read the full review. McDowell has her own blog, here, on blogspot unfortunately which makes it harder to subscribe for new posts and comments. Still, given her review in The Scotsman I suspect her blog would be well worth taking a look at.

Filed under: Welsh, Louise Tagged: Louise Welsh