Note: This is a stand-in for an idea that needs to be more fully developed.

The problem posed by form

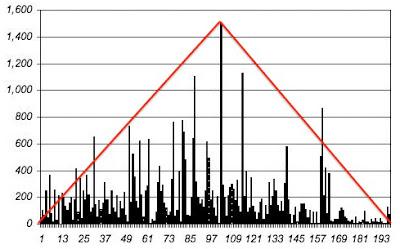

Not long after I began working on Heart of Darkness I discovered that a sentence a bit past the middle was by far the longest sentence in the text and that, when you charted sentence lengths from beginning to end, you get this:

There is clearly an order here, or is there? I don't want to go through the whole argument here - you can find it in my working paper on Heart of Darkness ( HERE or HERE) - but, in the case of that longest paragraph, I note that, in a text where Kurtz is a central figure, that's the first time we learn much about him. In fact, we get a précis of his life. Moreover, that paragraph is bracketed by the death of the helmsman, who falls bleeding to the deck just before it and his corpse gets kicked overboard just afterward. That structurally central paragraph is thus very strongly marked.

One can imagine, of course, that Conrad did this according to some conscious and deliberate scheme of paragraph lengths. But we have no evidence of that. If it did not come about through conscious deliberation, then just HOW did it come about? That's the problem, and it extends not just to that longest paragraph, but it to the whole text, particularly the second and third longest paragraphs, which come respectively after and before that longest paragraph.

How local intention can give rise to emergent order

I have a story to tell. It's just that, but I've been sleeping on it for a few weeks now and I still like it, crude though it is.

We know that Conrad originally published Heart of Darkness in three pieces. Let us assume that he had at least a rough idea about how things would go from the beginning. Frankly, I can't see how he could have done it any other way. It's not as though Heart of Darkness has an intricate Dickensian plot that has to work its way out.

So, he knew that Kurtz was brilliant but insane, that he was sickly - thus explaining why no one had heard from him - and would die before the steamer made it back down the Congo, that he was betrothed to some woman, and that the story would end with Marlow having a conversation with that woman. He also knew that, while Kurtz would be named in the first installment, that we wouldn't actually meet him in it. We wouldn't meet him until the final installment, but Marlow would reach the Central Station at the very end of the second installment, though without meeting Kurtz.

But, and this is crucial, he wanted us have a précis of Kurtz's story before we finally meet him the last component. [ Why? Good question, but let's leave it alone for now.] And so he has a technical problem: How do I bring this about? Technical problems have technical solutions, in this case, the double-narration - as we will see. Now, I can just as easily imagine that Conrad hit upon the idea of double-narration early in the game (remember, Emily Brontë used it in Wuthering Heights) and then asked himself: What can I do with this? It works either way.

This is how it works. The steamer is attacked a couple of hours before it gets to Central Station and the helmsman is killed. This is a "natural" incident for this kind of story; readers expect, no require, something like it to happen. When he's told his onboard interlocutors about the helmsman dropping bleeding to the deck, Marlow is so shocked and moved that he interrupts his narrative and addresses them. He takes this occasion to deliver the précis of Kurtz's career and ends that little recital with the comparison between Kurtz and the helmsman. He ends that comparison by observing that he did not set a higher value on the life of his helmsman than he did on the Kurtz's life. Why, after all, Kurtz was remarkable in all sort of ways his helmsman was not? Why? Because he knew and had worked with his helmsman; there was a bond there. But Kurtz, no bond at all; Kurtz was just an embodied pile of abstractions.

And THAT's what we take with us into the third installment. By the time we finally meet Kurtz we already know his story and we have Marlow's judgment on the relative value of Kurtz and the helmsman.

I can imagine, as well, that just as Conrad planned to have Marlow end with a conversation with the Intended, he also planned to have Marlow get his job through the agency of women - his aunt, the secretaries. He need not have explicitly thought "I'm going to end with a women and begin with women", but that simply followed from other considerations. Similarly, when he begins his précis it was all but natural for him to assert that it wasn't about the women when, in fact, in some ways it was all about them.

And so we have our story with the longest paragraph, the précis, in the structural center, flanked by the death of the helmsman. No need for top-down planning. It simply followed from the logic of the narrative situation.

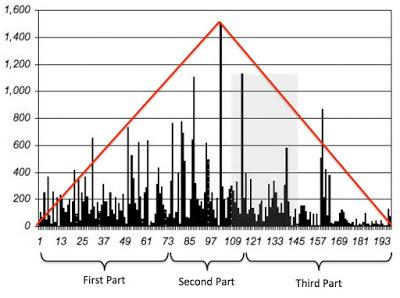

This chart shows some structural markers, the boundaries of the three sections in which the text was published, plus the portion (in light gray) actually spent at the Central Station:

Moving on, I note that that third longest paragraph [#88], the one before the structural middle, is about the African crew and establishes Marlow's estimate of them:

[...] They had been engaged for six months (I don't think a single one of them had any clear idea of time, as we at the end of countless ages have. They still belonged to the beginnings of time-had no inherited experience to teach them as it were), and of course, as long as there was a piece of paper written over in accordance with some farcical law or other made down the river, it didn't enter anybody's head to trouble how they would live. Certainly they had brought with them some rotten hippo-meat, which couldn't have lasted very long, anyway, even if the pilgrims hadn't, in the midst of a shocking hullabaloo, thrown a considerable quantity of it overboard. [...] Why in the name of all the gnawing devils of hunger they didn't go for us-they were thirty to five-and have a good tuck in for once, amazes me now when I think of it. They were big powerful men, with not much capacity to weigh the consequences, with courage, with strength, even yet, though their skins were no longer glossy and their muscles no longer hard.

FWIW, it's also the one place, other than pronouncing Kurtz dead, where an African speaks. They're talking about the possibility of being attacked from the shore:

It was very curious to see the contrast of expressions of the white men and of the black fellows of our crew, who were as much strangers to that part of the river as we, though their homes were only eight hundred miles away. The whites, of course greatly discomposed, had besides a curious look of being painfully shocked by such an outrageous row. The others had an alert, naturally interested expression; but their faces were essentially quiet, even those of the one or two who grinned as they hauled at the chain. Several exchanged short, grunting phrases, which seemed to settle the matter to their satisfaction. Their headman, a young, broad-chested black, severely draped in dark-blue fringed cloths, with fierce nostrils and his hair all done up artfully in oily ringlets, stood near me. 'Aha!' I said, just for good fellowship's sake. 'Catch 'im,' he snapped, with a bloodshot widening of his eyes and a flash of sharp teeth-'catch 'im. Give 'im to us.' 'To you, eh?' I asked; 'what would you do with them?' 'Eat 'im!' he said curtly, and, leaning his elbow on the rail, looked out into the fog in a dignified and profoundly pensive attitude.

And that second-longest paragraph [#115], which comes after the structural middle, much of it is spoken by the Russian after Marlow had disembarked at Central Station. The Russian gives us his estimate of Kurtz:

The man filled his life, occupied his thoughts, swayed his emotions. 'What can you expect?' he burst out; 'he came to them with thunder and lightning, you know-and they had never seen anything like it-and very terrible. He could be very terrible. You can't judge Mr. Kurtz as you would an ordinary man. No, no, no! Now-just to give you an idea-I don't mind telling you, he wanted to shoot me too one day-but I don't judge him.' 'Shoot you!' I cried. 'What for?' 'Well, I had a small lot of ivory the chief of that village near my house gave me. You see I used to shoot game for them. Well, he wanted it, and wouldn't hear reason. He declared he would shoot me unless I gave him the ivory and then cleared out of the country, because he could do so, and had a fancy for it, and there was nothing on earth to prevent him killing whom he jolly well pleased. And it was true too. I gave him the ivory. What did I care! But I didn't clear out. No, no. I couldn't leave him. I had to be careful, of course, till we got friendly again for a time. [...] Mr. Kurtz couldn't be mad. If I had heard him talk, only two days ago, I wouldn't dare hint at such a thing.

And it is in this paragraph that Marlow realizes that Kurtz had ringed the station with heads on stakes.

So, the longest paragraph in the text, which I have called the Nexus, gives us a précis of Kurtz's career and ends with Marlow judging that Kurtz's life wasn't worth that of his African helmsman. That third longest paragraph, before the Nexus, is about the African crew, while the second longest paragraph, after the Nexus, is again about Kurtz, but as seen by the Russian and as Marlow himself observes the station.

That all makes tactical and strategic sense - in the tactics and strategy or narrative organization, of course. There is more to be said, and so forth. But later.

Do I believe this?

More or less, yes, as far as it goes. I certainly can't prove it in any direct way. I have no access to Conrad's thoughts as he was writing. But it seems plausible.

And it makes that remarkable structure seem less puzzling. Yes, it is the result of authorial intention, but intention is like the proverbial iceberg, most of it is below the sea, only a tenth or so is visible above the surface. That tenth, of course, rests on what's hidden.