Villa-Lobos’ Yerma – poster art (sagradocacete.wordpress.com)

Villa-Lobos’ Yerma – poster art (sagradocacete.wordpress.com)After Magdalena, Heitor Villa-Lobos’ only other stabs at the theatrical genre were the opera Yerma (1955-56), written in New York and Paris to a Spanish text based on the 1934 play by poet-dramatist Federico García Lorca; and his final subject for the stage, the children’s fairy-tale musical A Menina das Nuvens (“The Girl from the Clouds,” 1957-58), given a paltry number of posthumous presentations in Rio and São Paulo’s Municipal Theaters.

As his most ambitious and innovative vocal work yet, Yerma was an atypical oeuvre in the canon of the confirmed Brazilian nationalist. But if the operatic idiom was still an unfamiliar dialect to him, certainly the play’s tightly-knit structure (three acts with two scenes each) and dramatic plot devices (the clash of earthly frustrations with magical and supernatural elements) stirred Villa-Lobos to new heights of lyricism.

The central character of Yerma is one of those incredibly demanding soprano roles requiring the vocal resources of a Leontyne Price mixed with the dramatic capabilities of Maria Callas. The story bears a striking resemblance to German composer Richard Strauss’ Die Frau ohne Schatten (“The Woman without a Shadow,” 1919) in its psychological depiction of the eternal feminine and the archetypal yearning for motherhood, albeit transplanted to rural Spain.

In brief, a peasant woman named Yerma (derived from the Spanish word yermo, or “barren”) wrestles with her insatiable desire for children and the indifference of her husband Juan, who prefers working in the fields to raising a family of four. Yerma ponders an affair with the young shepherd Victor, but her honor prevents her from taking up the matter with the youth as her lover.

With her marriage turning to bitterness and her husband’s subsequent recriminations and false accusations of infidelity, Yerma’s frustrations with Juan for his using her “for sexual rather than procreative purposes” boil over in Act III, leading to his death by strangulation at her hands. The tragedy of the piece, according to a 1989 Tempo article, “is that in killing Juan the chance of a child dies with him, and [Yerma] remains imprisoned by her childlessness even more.”

“I myself have killed my son!” she cries at the end. Unfortunately, the opera focuses almost exclusively on the vocally exhausting title part, with the additional negative factor of “too little dramatic variety and characterization” in the remaining dramatis personae.

Yerma never saw the light of day during the composer’s lifetime, and, as a result, went unperformed until New Mexico’s Santa Fe Opera finally mounted a production of it on August 12, 1971, a full twelve years after his demise. A Time magazine article dated August 23, written a few days after the opera’s premiere, revealed that Santa Fe’s stage director, Basil Langdon, had heard of the Villa-Lobos score, “secured the rights” to the work, and “determined to produce it in the original Spanish.”

That task took him a total of thirteen years, which resulted in Yerma’s world premiere, in Santa Fe, in the Spanish language version that Villa-Lobos had initially set to music. Despite the sophisticated soundscape and numerous references to the styles of Puccini, Debussy and Arnold Schoenberg, along with “an undertone of suppressed sexuality running through the whole score,” Yerma did not catch on with audiences or with other opera houses.

There have been subsequent attempts to revive the piece: the first one, in 1983, in Rio de Janeiro, which was deemed its premier presentation on Brazilian soil; and the second, in England, in July 1989. About the British production, music critic Guy Richards remarked at the time that Villa-Lobos’ orchestration, as in all his mature works, was “highly individual, full of quirks that tease the ear, but always light and airy… and never overwhelming.” Not exactly the most ringing of endorsements as far as reviews go, but a fair-minded assessment nonetheless.

On a side note, Villa-Lobos dedicated the work to his mother-in-law, Hermenegilda Neves de Almeida, on Mothers’ Day, appropriately enough. An even more fascinating aspect is the theme of the original play, which apparently appealed to the composer, in that “the premise of the social ostracism of an infertile woman was a highly personal one… because,” in the words of Villa-Lobos’ biographer David P. Appleby, “he had never had any children of his own.”

Could this be a Freudian interpretation of real-life events? Perhaps. But children or no, Yerma miscarried just the same, and has languished in undeserved obscurity for the better part of half a century.

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs

The same could be said for his joyous Menina das Nuvens, although this work’s performance history has lately been less checkered than that of its immediate predecessor.

Dedicated to his wife Mindinha, with a text by Brazilian playwright Lúcia Benedetti, one of the founders of the Teatro Infantil (Children’s Theater) movement in Brazil, A Menina premiered in Rio on November 29, 1960, a year after Villa-Lobos’ passing. Soprano Aracy Belas Campos interpreted the title role, along with tenor Assis Pacheco, baritone Paulo Fortes, bass Guilherme Damiano, and conductor Edoardo de Guarnieri.

The work’s libretto is said to lie “somewhere between Cinderella and The Wizard of Oz,” but instead of a magic slipper, “it is a cloth made from the rays of the moon” that becomes the “deciding factor.”

The actual plot concerns a girl who has been brought to the clouds by a bird and is raised there from infancy into early adulthood. Upon learning of her origins the girl expresses a strong desire to get back to her terrestrial family. Complications ensue, as one might imagine, but all ends happily, as most fairy tales are wont to do, with her marriage to a handsome young prince.

The critics and public remained divided in their responses to the work, which, for a children’s opera, has its longueurs. Given its creators’ reputation, they were not as receptive to The Girl’s charms as one would have expected, the main objection being its overuse of recitative (with a preponderance of “melancholy tones”) and the lack of a consistent musical viewpoint.

Journalist Irineu Franco Perpetuo, reporting on a September 2009 revival at the Palácio das Artes in Belo Horizonte, noted that Menina das Nuvens suffers from “excessive length” and complained of “some banal writing by Villa-Lobos in the first two acts. But it all comes together in the third… where the lush orchestration and neo-romantic Villa-Lobos of the 1950s meets the melodic serenades of the 1930s, in addition to some rhythmic and harmonic daring from the 1920s.”

One of its tuneful glories, we would like to point out, is the lovely ode for soprano that opens Act III, “Ó Lua redonda” (“O Moon so round”), done in the form of an “invocation to the moon”; in style and in substance, it brought to mind an earlier set-piece, the Song of the Moon, from the late Romantic period: the opera Rusalka, written by another, better-known European nationalist, Czech composer Antonín Dvořák.

You can judge for yourself how thoroughly delightful this episode is — when heard in its proper theatrical context, of course — in the following YouTube excerpt from the 2009 Palácio das Artes production. The titular Girl from the Clouds is exquisitely sung by Gabriella Pace, winner of the 2010 Carlos Gomes Competition; the bug-eyed Soldier is humorously played by tenor Flávio Leite, and the Westerly Wind is voiced by bass Homero Velho: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y5CJ81bkMAQ.

This same production was transferred to São Paulo’s Teatro Municipal in August 2011, with most of the original cast intact. William Pereira provided the direction and scenic design, with candy-colored sets by Rosa Magalhães and subtle lighting by Pedro Pederneiras. The work was arranged and conducted by Roberto Duarte, whose arduous task it was to organize and put order to Villa-Lobos’ chaotic material.

“Opportunities to familiarize oneself with Villa-Lobos’ operatic inclinations are exceedingly rare,” wrote reviewer Alexandre Freitas for Carta Capital’s online edition. “A large portion of his output is all-but unknown to the general public. For that reason, A Menina das Nuvens presents the perfect occasion to draw ever closer to Brazil’s main exponent of so-called classical music… In any form, it is a work that should be presented, performed, recorded, published and circulated as widely as possible.”

A “Forest” of Troubles

An amusing footnote to Villa-Lobos’ long musical career focuses on his Hollywood commission to write a music score for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s 1959 film adaptation of the old W. H. Hudson potboiler, Green Mansions.

Directed by actor Mel Ferrer, the movie starred his talented wife, the delicate but miscast Audrey Hepburn (War and Peace, Breakfast at Tiffany’s), as Rima, the “bird-girl” of the Amazon, and the boyish Anthony Perkins, in his pre-Psycho period, as the blasé love-interest. The other denizens of the studio rain forest included such equally out-of-place heavies as Lee J. Cobb, Sessue Hayakawa, Henry Silva, and Nehemiah Persoff.

With typical motion-picture logic, the film’s producers informed the master musician of their intention not to have him orchestrate his work — actually, a standard studio practice at the time, but which totally infuriated the usually unruffled Brazilian. MGM further compounded the offense by releasing the finished product with most of the music credited to composer Bronislau Kaper, a more-established movie veteran, who had previously scored the delightful Leslie Caron vehicle Lili (1953), in addition to other gems for the silver screen.

Not that Villa was so naïve about movie-making that Hollywood took unfair advantage of his ingenuousness, but his unfamiliarity with how things were done in filmdom astounded even a veteran film composer of Miklos Rozsa’s repute:

“I met [Villa-Lobos] when he arrived in Hollywood, asked him whether he had yet seen the film and how much time they were allowing him to write the music. He was going to see the picture tomorrow, he said, and the music was already completed. They had sent him a script, he told me, translated into Portuguese, and he had followed that, just as if he had been writing a ballet or opera. I was dumbfounded; apparently nobody had bothered to explain the basic techniques to him. ‘But Maestro,’ I said, ‘what will happen if your music doesn’t match the picture exactly?’ Villa-Lobos was obviously talking to a complete idiot. ‘In that case, of course, they will adjust the picture,’ he replied. Well, they didn’t. They paid him his fee and sent him back to Brazil.”

For his part, the wily Villa took his own “advantage” of Hollywood’s callous disregard for his abilities by re-fashioning the completed score into a large-scale symphonic tone poem for soprano, male chorus, and expanded orchestra. He renamed it A Floresta do Amazonas, or “Forest of the Amazon,” a title that recalled, and paid belated tribute to, his earlier wanderings into the rain forest region.

Four love songs written expressly for the film, but never incorporated into the final cut had their concert premieres at New Jersey’s Palisades Park on July 12, 1959. Madame Dora Vasconcelos, the former Consul-General of Brazil in New York, provided the lyrics for the unused numbers.

The richly exotic treatment of this colorful orchestral epic was everything one could expect from so fiercely independent and astute a musical artist as Villa-Lobos; it was, simply put, a classic case of Hollywood’s loss and the concert hall’s gain.*

The work (along with the four love songs) was committed to posterity in 1959 by United Artists Records, with the difficult soprano part taken by the legendary Bidu Sayão, who came out of her early retirement as a special favor to the conductor of the recording sessions: her most esteemed friend and admirer, the gravely-ill composer.

There have been several complete recordings of Forest of the Amazon, including a highly recommended 1995 version with the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Villa-Lobos expert Alfred Heller, and starring American prima donna Renée Fleming who brought Rima the bird girl to vivid vocal life.

Postlude: The Villa-Lobos Legacy

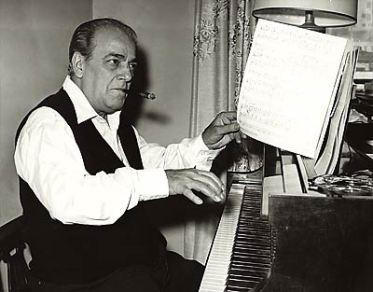

Heitor Villa-Lobos eventually succumbed to the bladder cancer that had been temporarily halted by the operation he had undergone a decade earlier.

Four months before his death, however, Villa-Lobos received the prestigious Carlos Gomes Medal as part of the festivities commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the opening of the Teatro Municipal in Rio de Janeiro.

One could make the argument that this award was a rather dubious honor, what with his having produced no operatic masterwork of any lasting renown. On the contrary, he had done more for Brazilian music education, and for Brazilian social awareness of music’s beneficial properties and potential, than any other national celebrity before or after him.

“He enriched the lives of various generations of students and guided the musical direction of an untold number of future artists,” went an official New York University document from 1959 dedicated to the composer’s work. “A vibrant personality, gifted with an infectious and communicative enthusiasm, his reputation has expanded throughout the known world as a brilliant creator of modern music.”

A more appropriate postscript might have included his equally infectious — and frequently sly — sense of humor:

“Artists live with God – but give their little finger to Satan. I sleep with the angels and dream of the devil.”

— Heitor Villa-Lobos

Although not the prophesied savior of the Brazilian national opera, Villa-Lobos was without doubt the most famous and highly regarded native-born classical musician in memory.

Who would have thought that another citizen of the state of Rio, the pert and petite Bidu Sayão, would become, as a result of championing Villa-Lobos’ works and following Toscanini’s baton beat, the person most linked in the minds of the theater-going public with the very best that Brazil had to offer in operatic circles; and the country’s foremost international proponent of the Italian, French — and Brazilian — repertoires. ☼

Copyright © 2014 by Josmar F. Lopes

* The movie Green Mansions was not the composer’s first attempt at a film score, since, as we already know, Villa-Lobos had begun his long association with the cinema during the silent-movie era, as part of the music-band at the Odeon Theatre in Rio. He was later commissioned by the Vargas administration to provide the music for a patriotic picture, O Descobrimento do Brasil (“The Discovery of Brazil,” 1936-38), which was transformed by Villa into a four-movement concert suite of themes of the same name.