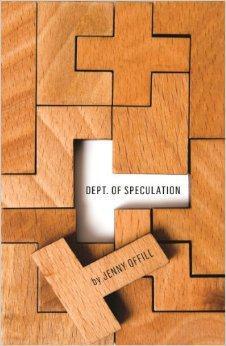

Dept. of Speculation, by Jenny Offill

This is perhaps the best written unmemorable book I’ve ever read. I could be wrong in that of course. The trouble about unmemorable books is it’s hard to rank them in memory.

I read Dept. shortly before going on a three-week holiday in the US. It’s a novella, under 200 pages but with lots of space and it’s a very quick read. It came very highly recommended and as I read it I was blown away. I thought it a shoo-in for my 2015 end of year wrap-up.

Now, some five or six weeks later, I look at the passages I noted and I recognize them but they’re islands of prose. There’s a popular type of image to use when depicting Canary Wharf, London’s second financial centre; corporate glass and steel towers rising out of clouds, isolated and aloof. Here’s an example:

Writing this today, that’s how Dept. is for me. I have the quotes I’ll include in this piece, but otherwise it’s completely lost.

The narrator is a creative-writing teacher in Brooklyn (I know, bear with me here for a moment). Her partner (husband? I don’t remember) records street and nighttime sounds which he uses to make abstract electronic music. These are all real things of course. I read novels by Brooklyn authors (this is one). I listen to quite a lot of field-recording electronic music. Still, it’s fair to say we’re in a bubble here.

Another night. My old apartment in Brooklyn. It was late, but of course, I couldn’t sleep. Above me, speed freaks merrily disassembling something. Leaves against the window. I felt a sudden chill and pulled the blanket over my head. That’s the way they bring horses out of a fire, I remembered. If they can’t see, they won’t panic. I tried to figure out if I felt calmer with a blanket over my head. No I did not was the answer.

The narrator and her partner met, they fell in love, they had a kid, they have relationship problems. That’s pretty much the story, such as it is, and what more do you need? For most of us our dramas are domestic, and better that than to live through wars and famines.

Dept. is written in fragments of thought. Each paragraph is a reflection, a moment, a passing mental connection. That’s its chief strength, because much of it feels true to how we think, or how I think anyway. It isn’t chronological but rather goes back and forth flitting from thought to memory to thought. It’s like Buddhist meditation where you allow your mind to wander as it wishes and observe it as it does so, but somehow remain separate from it.

Antelopes have 10× vision, you said. It was the beginning or close to it. That means that on a clear night they can see the rings of Saturn. It was still months before we’d tell each other all our stories. And even then some seemed too small to bother with. So why do they come back to me now? Now, when I’m so weary of all of it.

As an aside, I tried Buddhist meditation once. I am it turns out not yet ready to be enlightened. My mind chatters loudly. So it goes.

When it works, which is almost all the time, it works superbly well. I was absolutely captured by Offill’s voice. The paragraph-thoughts are neat and clearly very carefully crafted but that’s fine, the narrator is after all a Brooklyn novelist and anyway novels are by their nature inherently artificial. Offill has a meticulous eye and an understated sense of humor and I found this an effortlessly easy read – a standing contradiction to the false dichotomy between readability and literary quality.

Themes emerge (or I assume they do based on the paragraphs I noted at the time), most notably the challenge of “the unsatisfactory nature of ordinary experience”. The narrator and her partner are both artists, but art demands dedication and life demands compromise. In the early days:

I learned you were fearless about the weather. You wanted to walk around the city, come rain come snow come sleet, recording things. I bought a warmer coat with many ingenious pockets. You put your hands in all of them.

That can’t last though. Now the narrator spends her days looking after her child, trying her best to make something interesting of her day to tell her partner when he comes home. Their lives aren’t in each other’s pockets anymore, and she hasn’t turned out to be the selfish “art-monster” caring about nothing but her craft that she once dreamed of being. It’s not so much that she resents the life she has (she loves her child and her partner, even with their current problems), but rather that the gradual brutality of adapting to the ordinary wearies her.

Some women make it look so easy, the way they cast ambition off like an expensive coat that no longer fits.

It’s not quite what I’d call universal, but it’s not rare either. Almost anyone who spent university talking philosophy and art and drinking in late night bars will recognize the shock of finding yourself having to get to work on a Wednesday morning. How did all that come to this? Why does all that always seem to come to this? There are good answers, but not always satisfying ones.

I mentioned Offill’s sense of humor. Part of it manifests in gently mocking her own craft:

Advice for wives circa 1896: The indiscriminate reading of novels is one of the most injurious habits to which a married woman can be subject. Besides the false views of human nature it will impart … it produces an indifference to the performance of domestic duties, and contempt for ordinary realities.

Or:

My friend who teaches writing sometimes flips out when she is grading stories and types the same thing over and over again. WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE? WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE?

This is not of course a novel where most of the time you have the faintest idea where you are in time and space. It’s also that theme again, art and mundanity. Teaching writing, which is teaching art, reduced to marking piles of repetitive scripts. You might as well work in an office, at least you’d get the evenings off.

Oddly, the only passage that didn’t work for me at all was the one that justified the title. At one point the narrator observes:

They used to send each other letters. The return address was always the same: Dept. of Speculation.

Even for Brooklyn artists I just didn’t buy that. Of course, for all I know that’s a detail Offill took from her own life or from some friend’s anecdote. It could be completely real. It doesn’t matter though because it’s not convincing. Dept. is a deeply artificial novel both in terms of style and structure (“It’s important to note the POV switch here”) flipping between first and third person as the narrator feels closer to or more distant from her partner. It’s delicate and intricate and beautifully worked. At that moment though the soap-bubble just popped for me and for the first time I didn’t believe it. It was an oddly false note and at the time I thought would be my only criticism.

Now though, now my criticism is that Dept. is a snowflake of a novel that glitters beautifully but vanishes away to nothing. I don’t know that’s necessarily a bad thing. Not every novel has to mark your life, but it is a troubling thing. As I write this I can call passages and scenes and even the shape of the text from say Cassandra at the Wedding effortlessly to mind but here I had to quote every passage I noted because otherwise I had nothing to hold on to.

Other reviews

John Self of TheAsylum reviewed this for the Guardian, here, and there are some comments about it on his blog also here. He didn’t have any issues remembering it, but then he read it twice before reviewing it which may have helped. An unscientific poll on twitter suggests I’m not alone in having loved it but then having forgotten it. John also interviewed Jenny Offill on his blog, here, and it’s an illuminating interview in terms of influences and structural choices.

Trevor of themookseandthegripes also reviewed this, here. It’s been quite widely reviewed so as ever please feel free to let me know of reviews I’ve missed in the comments.

Format

Finally, I read this on kindle. You shouldn’t. Formatting and layout matters here and Offill even gave thought to the typeface (which is lost on Kindle). If you are going to read this, and despite what is at times a moderately negative review I do still recommend it, read it in hardcopy.

Filed under: Offill, Jenny Tagged: Jenny Offill