In an industry with such monumental growth in recent years, it's no wonder people are asking all sorts of questions these days. Interest for beer is at an all-time high, which means curiosity among enthusiasts is right there to match.

Lately, however, if people aren't asking "what's the next IPA?" it's been something along the lines of "when do you think this bubble will burst?" The fate of beer is a popular armchair quarterback activity, often based on ideas of vanity stats like the number of breweries in the country instead of where things stand culturally and economically.

In 2011, there was fear of a bursting bubble because 2010 offered record growth for craft beer. Then again in 2012. And 2013. Of course in 2014. Definitely in 2015. And the song plays on.

Sometimes I feel this discussion is almost as ubiquitous as putting beer into cans.

At the core of each of those news stories - and most conversations I've had on the topic - is that people see the fast growth in overall number of US breweries, try to translate what that number means to them personally and assign a judgment based on their expectations and experiences, assuming things must be heading in a bad direction.

But what if Sam Calagione's " bloodbath " of fallen craft brewers isn't coming? That was a prediction made two years ago, after all.

Instead, what we've seen over the last five years is an influx of smartly created businesses increasing sales and prices - all the while met by demand.

My first thought when discussing a "bubble" isn't necessarily an economic take, but a psychological one. The people who are often crying wolf on the impending crisis are typically media covering the industry. Not intense, card carrying Beer Nerds such as myself, but a traditional reporter with an average knowledge of beer who may care to ask questions about a bubble when local brewery numbers creep upward, like these examples for Los Angeles or Minneapolis-Saint Paul.

Even when beer enthusiasts do ask about bubbles, it comes from our unique point of view, trying to combine what we know and see about our local and regional market with context of the national scene to create some mental conglomeration of impending doom.

On a whole, unfamiliar things make us more afraid than familiar ones, especially things have been mythologized as "scary." Discussions of past bubbles - whether the tech or metal or beer industries - adds to a mounting collection of references that tell us we should be weary when something grows fast. On top of that, add ongoing coverage asking about a bubble and why we should be worried and we begin to inch toward instructional fear acquisition, a social cost of fear, whether rational or not.

The process of layering public perception, often seen through continuous coverage or mention of our beer bubble, on top of mirroring the fear of others can lead to irrationality, hardly an uncommon attribute for humans in all aspects of life.

In an unrelated field, perhaps we can take a cue from Indiana University telecommunications professor Andrew Weaver: "When you leave it up someone's imagination, we can conjure things that can frighten us much better or effectively than what most filmmakers can invent and put onscreen."

The most common area from which people base their fear of a beer bubble comes from the rising number of breweries, but a vanity stat doesn't tell the whole story. If we were to have a thousand regional breweries making 50,000 barrels a year coming online, that would most certainly sound like a problem. But it's commonly the exact opposite.

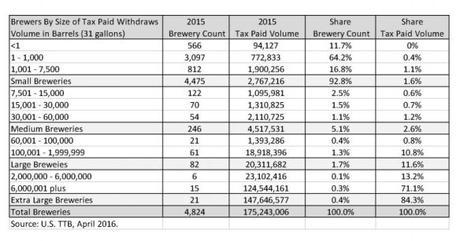

According to estimates by the National Beer Wholesalers Association (NBWA), the beer industry added about 700 new breweries in 2015, which aligns with the Brewers Association's estimate of about two breweries opening each day. As the NBWA's Lester Jones points out, "starting small is the name of the game."

Most breweries entering the marketplace these days are small. "Nano" isn't just a descriptive word for a brewery's size, but it's a trend in the industry.

From 2007 to 2015, the average barrel production for microbreweries (less than 15,000 barrels a year and selling at least 75 percent off-site) declined from 2,290 to 1,638 barrels, according to Brewers Association estimates. That can be because of factors like some breweries scaling up and leaving the "microbrewery" label behind, but is mostly driven by the entrance of small businesses.

Not only does staying small offer greater potential for business success based on scale and margins, but it's simply a return to normalcy for America's brewing industry. The neighborhood breweries of the 19th century have returned, offering intimacy and authenticity at a time when expectations among the beer drinking public are changing, especially craft beer lovers.

"Fears about the number of breweries are often overblown because people haven't wrapped their head around what the new brewery business model really is for these businesses," Brewers Association economist Bart Watson recently mentioned on the Business of Craft Beer podcast.

Small is increasingly playing a bigger role in beer. In the same conversation, Watson mentioned the contrast between craft brewery growth 20 years ago versus today. Back then, brewery geography was focused on places like college towns and urban areas. Now, with a reported 78 percent of drinking-age adults living within 10 miles of a brewery, those locations have diversified.

"You don't get a stat like that unless you have breweries in the vast majority of communities around the country," Watson said. Given that the popular business model of focusing on staying small and local has taken hold, "that's something that a neighborhood in a city or small town can support," he added.

One of the biggest differences between the beer industry's "Shakeout" of 20 years ago and today is demand.

Overall, the rise in number of craft breweries simply parallels the increase of "craft" goods and services in other industries. This doesn't just apply to the United States, but acts as a global movement as well. In one study looking at 118 countries, findings showed that "most regions and markets worldwide last year saw consumers trading up to higher value products across a wide range of categories." There's a rise of craft producers everywhere.

Most important, people are willing and able to pay for the increased amount of beer available in the marketplace. The high-end segment of beer - crafts and imports that cost more than $30 a case - is growing steadily, according to the National Beer Wholesalers Association. Wages may need to grow a little faster, but overall consumer spending is healthy.

In terms of Brewers Association-defined "craft" beer, volume and dollar sales are up. Breweries charging $20 for a four-pack of New England IPA are selling out on a daily basis. While some beer is most certainly sitting on store shelves longer than before - an unfortunate side effect of the power and volume of choice - stale beer we find at our local bottle shop isn't necessarily indicative of national trends.

Yet, at least.

Just remember, we've been sounding this alarm for some time. Even in 1994, when Portland, Maine was getting ready to open its fifth brewery, the end was nigh.

With any business system, there are always economic aspects to consider and worry over, but even though we only have to look back 20 years to see a busted bubble in the beer industry, we shouldn't start pounding the alarm just yet. It's not all doom and gloom. It's not all threatening. It's actually kind of exciting.

@BrewersStats I have gotten less calls from people saying they will sell 60k bbls their first year... so I guess that's a good sign.

- Scott Metzger (@beermonkey) August 17, 2016

Bryan Roth

"Don't drink to get drunk. Drink to enjoy life." - Jack Kerouac