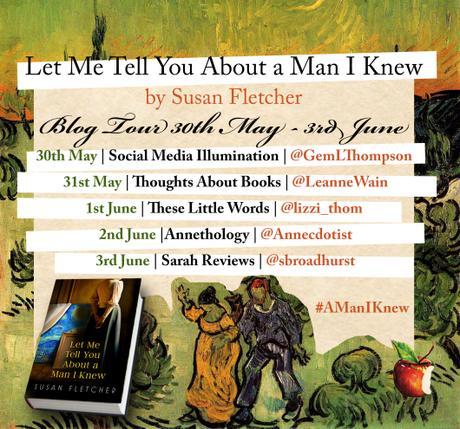

This post is part of the blog tour for Let Me Tell You About A Man I Knew - be sure to check out the other posts!

I was very glad to be offered a review copy of this book. The Little Brown website describes it as 'tender and savage' and this is certainly true - the pains and passions of life are explored and considered in all their beauty and horror. The descriptions of Provence are vivid and colourful, and took me right back to our holiday there last year. Fletcher obviously has a passion for the area she describes - a place filled with history and nature, and the lives of those who live there.

Van Gogh himself is very 'in touch' with nature in this novel, and seems happier to be out in it than in amongst buildings and people. He is troubled and vulnerable when we meet him, having recently committed that famous act of self-harm, severing the lower part of one of his ears, and now residing in a psychiatric hospital. To Jeanne Trabuc, the wife of his doctor, van Gogh is doubly mysterious as both a patient at the hospital and as an artist. She is captivated by his creativity and what she sees as his freedom from the constraints of an ordered life. She is mesmerised by the story of his ear, and the rumour that he once wandered into Place du Forum in Arles completely naked, in the rain, at night.

To Jeanne he represents freedom, creativity, boldness, and the potential richness of life. She compares him, sometimes unconsciously, with her own husband, Charles. He is professional and 'buttoned up', and lives by rules and routine. She herself is a housewife, forbidden to talk to the patients or go inside the hospital, left to her housework. When van Gogh arrives she is instantly intrigued by him, and actively seeks him out - in secret of course.

While van Gogh is the 'big name' here, the story is really about Jeanne, and her life and marriage. She reflects on the feeling of loss she has now that her children are grown up and living far away, and the loneliness she feels now that Charles insists on separate beds. The question of intimacy in their marriage - both psychological and physical - is an important theme to the novel and something that Jeanne thinks about often. The 'man' in the title is van Gogh, this mysterious artist, but also Charles. He is the love of Jeanne's life and yet sometimes she feels that she no longer knows him. Her passion is contained within her, and as she talks more with van Gogh and learns about his art and life, she realises that she must release it. She hears about his troubles and his pain, and realises that you must live with passion, and that life is beautiful. Her boldness grows throughout the novel and she refuses to settle for her lot. Jeanne is brave in her own small way, and she fights for what is worth having - her marriage and her happiness.

Let Me Tell You About A Man I Knew is a portrait of a time and a place, and a marriage. It is one of the most beautiful books I have ever read, and I recommend it highly.

The author Susasn Fletcher kindly agreed to answer some questions I sent her, which I hope will entice you to read this wonderful novel even more.

What drew you to write about Jeanne Trabuc? How did you get into her mindset and her life?I first became aware of Jeanne through Vincent's letters. I knew I wanted to write a novel about van Gogh; I also knew that I was interested in that year of his life - May 1889-1890 - where he was at his most prolific, in the olive groves of Saint-Remy. So I began to read his letters to Theo, from that time. Vincent's description of her - the warden's wife - was so astonishing that I felt compelled to find out more. She was a plain, middle-aged housewife who was unlikely to have either seen much of the world, or been educated well. This was my starting point: to imagine a life in which there weren't such luxuries, and how small such a life would be

Did you travel to Provence to get a feel for the environment and the buildings of the asylum?I did! And it was one of the most wonderful weeks. I stayed in a tiny annex, on the outskirts of Saint-Remy, and I'd walk along the lanes into the town every day. It was June, and everything was in blossom. The asylum itself is still there; it's still a working hospital, so the majority of it is inaccessible. But there's a small museum about van Gogh's stay at Saint-Paul, with a replica of his little room. I'd go to the hospital most days, walk through the fields surrounding it with my notebook. As for the Trabuc's cottage itself, I got conflicting information as to which it was, or where it had been - so I was left having to make my own guesses. Even so, I came back with such a vivid, strong sense of Jeanne and her life there. It was a turning point in the writing of the book.

Did you have to do much research into the treatment of and attitudes towards mental health in 19th century France? What did you learn?My research didn't, in fact, take me too far into the treatment of mental health in France in general. The two things that I did, however, need to know and understand were, firstly, what van Gogh suffered from - what he was prone to, how others perceived him and how he perceived himself - and, secondly, the regime at Saint-Paul. Saint-Paul was not particularly representative of other asylums, at the time, in that it focussed on simple diet, rest, regular baths and the freedom to write, paint or read. As for van Gogh's conditions, I think there's debate even now as to what he suffered from. The likelihood is that it was a combination of things: bipolar disorder and epilepsy are two strong possibilities.

How did you go about learning about Van Gogh's time at St Paul? What was the most interesting thing you learned about him?The best resource, by far, was the letters that he wrote to his brother during his stay. Van Gogh wrote to Theo throughout his life, and they were saved and published after his death by his sister-in-law Jo. Without them, we'd know so much less about him, and his life. What I loved most about these letters was that they show Vincent's tenderness, and vulnerability: I'd assumed they'd be troubled, hard, perhaps aggressive in their tone. In fact, they are beautiful meditations on his work, on life, his condition and his loneliness. He also had a sense of humour: there's a wonderful sentence in an early letter, from Saint-Paul, in which he laments the bland food there, and the downsides of the patients having so many beans!

Finally, what are you working on now?I'm frustratingly coy when it comes to talking about works in progress! But it's another historical piece, set in rural England before the First World War. I'm having to research flowers, at the moment - which is an absolute gift of a thing.

*

Published by Virago, an imprint of Little Brown, in June 2016. My copy was kindly provided by the publisher for review.

Available at Wordery and Foyles.