Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 book, The End of History, heralded liberal democracy’s apparent final triumph, fulfilling basic human aspirations. But alas, bad people also have aspirations — and often guns.

Francis Fukuyama’s 1992 book, The End of History, heralded liberal democracy’s apparent final triumph, fulfilling basic human aspirations. But alas, bad people also have aspirations — and often guns.

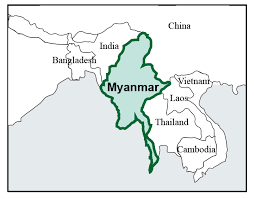

Cheerleading for democracy is frustrating. Hopes often raised, then betrayed. Visiting a democratic Russia — shortly after Fukuyama wrote — was thrilling. Then history returned. The story repeats again and again. As in the Arab Spring. In Thailand, and Sri Lanka, and elsewhere. Now Myanmar (formerly Burma).

The problem isn’t just guns. It’s also voters. Too few have read Fukuyama to understand how democracy serves them. Too many foolishly fall for strongmen. (America saved by its would-be strongman being himself a fool.)

The army had ruled since 1962. Democracy advocate Aung San Suu Kyi was under house arrest. She’d been heroic; her book, Freedom From Fear, an inspiration.

Suu’s luster dimmed when she refused to criticize, and even defended, the army’s savage genocide of rape and murder against Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims. (Buddhist pacifism?) Admittedly her tense relationship with the army circumscribed Suu’s power and authority; but she had some; and what good are they if you’re afraid to use them? Freedom from fear?

The paradigm of an army using its guns to rule is so familiar it seems inevitable, like the weather. How to keep soldiers in their barracks is a perennial conundrum. Yet few question why a country like Myanmar even has an army in the first place.

Myanmar does have internal conflicts, with regional/ethnic insurgencies, that its army battles. That sort of thing is what mainly occupies modern militaries — to the extent they do any actual military stuff at all. But query what would obtain absent a national army. The aggressiveness of Myanmar’s toward those regional elements is itself a major instigator of bloodshed. Without its army, the country would likely work through such conflicts politically, and peacefully.

What’s suggested here is not some utopian pacifist fantasy. Naturally, disbanding any army faces much opposition, not least from that army itself; which, after all, has guns to back up its resistance. (Myanmar’s proved unwilling even to coexist with a civilian government.) Yet a few countries have succeeded in abolishing national armies. Costa Rica, for example, did so back in 1948, after a civil war. It has not since experienced another, nor an invasion — nor, of course, a military coup. Its democracy thrives unmolested.

This is a practical path toward the pacifist dream of a world without war.