Irène Némirovsky (1903-1942) was on my ‘to read’ list for a long time before our reading group’s decision to read European novels made me take down one of her books. This turned out to be both timely and chastening, as in the early years of the 20th century Némirovsky was a refugee, making her way across Europe to France from Ukraine, then a part of Imperial Russia.

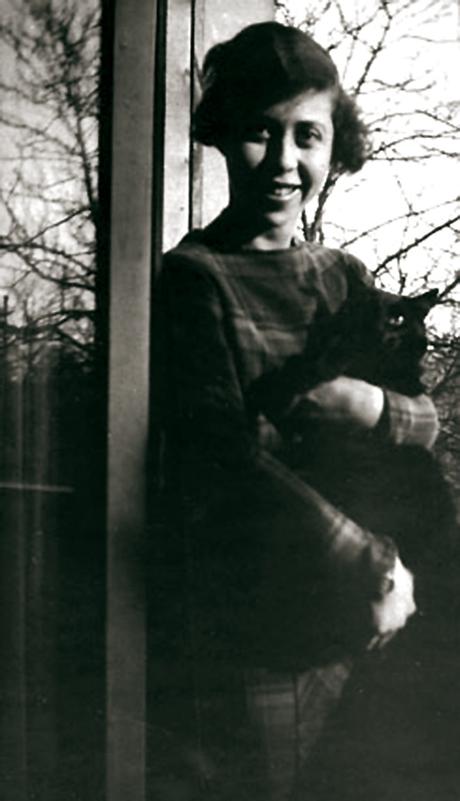

Irène Némirovsky at the age of 25 (public domain, from a scan of a family photograph by an unknown photographer)

Irène Némirovsky at the age of 25 (public domain, from a scan of a family photograph by an unknown photographer)

Le Bal and Snow in Autumn are early works, published when Némirovsky was in her late twenties. She was about 15 when she left Ukraine forever, and she must have known uncertainty, difficulty, fear and a sense of not belonging. Her experience pervades the very different stories of Le Bal and Snow in Autumn.

Snow in Autumn is the story of an aristocratic Russian family from the start of World War One, through the Revolution, to exile in France, and from riches to poverty. With all its potential for drama and romance, this is a common enough subject for a novel. Némirovsky’s tale is uncommon, although it has dramatic moments. It may not be strictly autobiographical, but sadness and bewilderment are everywhere. The story is further distinguished by being told almost entirely from the point of view of an elderly servant. Tatianouchka was perhaps born a serf, worked as the Karine family nurse for a couple of generations and has grown old in service. Her own people are long dead, and she has only the Karines.

At the beginning of the novella, she watches the latest generation ride off to war, feeling that change is coming and remembering her first master who did not come back from his war.

She forced herself to smile, pinching her lips even more; they had remained delicate, but were now tighter and pulled inwards, as if sucked into her mouth by her aging jaw. She was seventy years old, very small and fragile-looking, with a smiling, lively face; her eyes were still piercing at times, and at others, calm and weary.

Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 859-862, Kindle edition.

Her uneasy fatalism (so common in Russian literature) are shared across the family. ‘Children will grow, and old people will fret,’ says her current master to his wife, as Tatianouchka prays for the boys: ‘Hear me, Lord! Everything is in the hands of God.’ (Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 920-2, Kindle edition).

When we next see her, it is 1918, the family has fled and she is alone, loyally looking after their house and treasures:

It was a hushed May night, already sweet-smelling and warm. Soukharevo [the nearest village] was burning; she could see clearly the flames in the air and hear the sound of people’s screaming…

Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 1038-9, Kindle edition.

The Revolution catches up with her, of course, and she has to leave the estate for Odessa, where the Karines are living. It takes her three months, and she carries the family’s remaining ‘jewellery in the hem of her skirt’ (Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 1198, Kindle edition). She finds the Karines

… in a dark room near the port; sacks of potatoes had been hung from the window=panes to absorb the exploding bullets. Hélène Vassilievna lay on an old mattress on the floor; Loulou and André were playing cards by the light of a little stove, where three pieces of coal were nearly burnt out. It was already cold, and the wind whistled through the broken windows. … (location 1204-8, Kindle edition)

…

The winter was extremely harsh. They didn’t have enough bread or clothes. Only the jewelry that Tatiana Ivanova had smuggled back occasionally brought them some money. The city was burning; the snow fell softly, hiding the scorched beams of the ruined houses, dead bodies, and dismembered horses. At times, the city was different: provisions arrived, meat, fruit, caviar … God alone knew how … The cannon fire would stop, and life would begin again, intoxicating and precarious.

Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 1204-23, Kindle edition.

The descriptions have an extra resonance today, with Ukraine under fire again.

In time, the family and Tatianouchka make their way to France, and we see their mostly feeble efforts to make a new life. The children gradually abandon old ways, the parents struggle and Tatianouchka endures as long as she can, able to express her confusion only by grumbling about the strange French weather. Refugees like her and the Karines are merely ‘mouches d’automne’ (the novella’s original title):

The Karines remained in these four dark rooms until evening … Back and forth they went, between their four walls, silently, like flies in autumn after the heat and light of summer had gone, barely able to fly, weary and angry, buzzing round the windows, trailing their broken wings behind them.

Némirovsky, Snow in Autumn, location 1268-9, Kindle edition.

The second novel in the collection, Le Bal, is quite different. A newly nouveau riche couple, the Kampfs, decide to hold a grand ball, to launch themselves into high society. Madame is the driving force, and as the ball draws near, we see her nervy and vindictive treatment of husband, servants and 14 year-old daughter, Antoinette.

You know, Antoinette, you could stop what you’re doing when you see your mother,’ she barked. ‘Is your bottom glued to that chair? What refined manners you have!’ … ‘I believe I hired you,’ Madame Kampf began harshly [to the governess], ‘to look after and educate my daughter, and not so you could make yourself dresses. Does Antoinette not know she is meant to stand up when her mother comes into the room?’

Némirovsky, Le Bal, location 63-71, Kindle edition.

Antoinette is much like her mother (though she would deny this) and has in addition all the anguish of the 14 year-old.

Antoinette attempted a smile, but with so little effort that it merely distorted her features into an unfortunate grimace. Sometimes she hated grown-ups so much that she could have killed them, mutilated them, or at least stamped her foot and shouted, ‘No! Just leave me alone!’

Némirovsky, Le Bal, location 63-84, Kindle edition.

So when they clash over the ball, Antoinette cannot help but seize an opportunity for revenge, which is played out slowly across the rest of the story, as the tension increases.

These two novellas – the stories of an old woman and a young girl, refugees and French, impoverished and wealthy – may seem an odd combination, but in fact they are well-matched. Both feature characters out of place, written by a woman who was herself out of place. Tatianouchka is trying to come to terms with a new world; Madame Kampf is moving up in society; and Antoinette is growing up in an unhappy household. All three are prey to stress, bewilderment, anger and fear. Némirovsky shows herself to be an acute observer of human nature – her characters live, complete from their first appearance – and a skilled storyteller able to convey an intensity of emotion and experience in only a few pages.

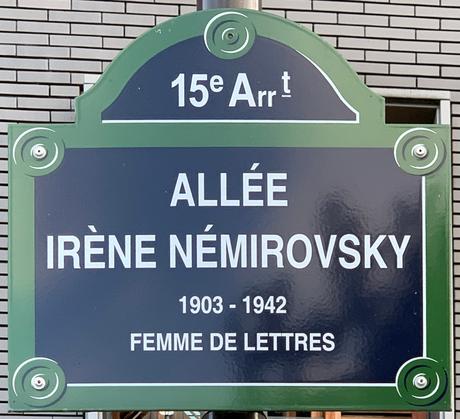

What Némirovsky might have become, we are not to know. When World War II broke out, although she had converted to Catholicism, she was arrested as a Jew, deported to Auschwitz and died of typhus. She was 39 years old. Although she assimilated well in her adopted home, she was refused French citizenship, forever a refugee in official eyes. Her husband died in Auschwitz too, but their two daughters remained in France and survived the war. It is through them, with their discovery of her contemporary Suite Française novels (about the German occupation of France), that she is now recognised as a ‘femme de lettres’ in her adopted country.

Plaque Allée Irène Némirovsky – Paris XV (image by chabe01, reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

Plaque Allée Irène Némirovsky – Paris XV (image by chabe01, reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)