Book review by Sue R:

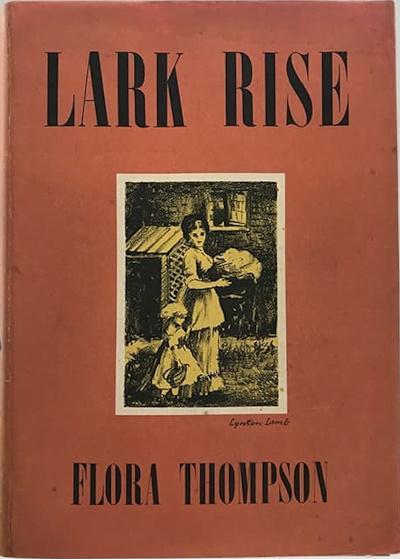

Flora Thompson wrote the three books which were published in one volume in 1945: Lark Rise(1939), Over to Candleford(1941) and Candleford Green(1943). The books are autobiographical in content. Laura, the main character, lives in a hamlet like Flora did, on the Oxford-Northamptonshire border; they both go to work in a post office in a nearby town and both wrote poetry.

The setting is the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: a period of transition when the age- old practices of farming, social structures and life in the villages were coming under pressure from the advent of modern inventions in agriculture, transport and manufacturing.

As the author says:

All times are times of transition; but the eighteen-eighties were so in a special sense, for the world was at the beginning of a new era, the era of machinery and scientific discovery. Values and conditions of life were changing everywhere. Even to simple country people the change was apparent. The railways had brought distant parts of the country nearer; newspapers were coming into every home; machinery was superseding hand labour, even on the farms to some extent; food bought at shops, much of it from distant countries, was replacing the home-made and home-grown. Horizons were widening; a stranger from a village five miles away was no longer looked upon as ‘a furriner’.

But, side by side with these changes, the old country civilization lingered. Traditions and customs which had lasted for centuries did not die out in a moment.

Work in Lark Rise was generally agricultural: the men were landless labourers with 10/- a week to keep their families. Their work was hard but not unskilled and changed with the seasons:

Very early in the morning, before daybreak for the greater part of the year, the hamlet men would throw on their clothes, breakfast on bread and lard, snatch the dinner baskets which had been packed for them overnight, and hurry off across fields and over stiles to the farm.

These men, when young and in their prime, “prided themselves on the weight they could carry”, and their ideal was endurance. The traditional farming methods still prevailed. Any machinery was horse-drawn: ploughing was done with cart-horses, the farmer did have a seed drill but often sowing was done by hand. There was a mechanical reaper but this only did some of the harvesting -men still mowed with scythes and some women used sickles. In the 1880s, some of the hamlet women did farm work though most regarded it as disreputable. Payday was Friday and wages were handed out by the farmer himself. The custom of the countryside was that the ten shillings were passed to their wives who gave them back one shilling as pocket money. I think the men got the better of the deal as the women had the worry of coping with insufficient resources.

The farmer no doubt thought he was a good employer:

How they managed to live and keep their families on such a sum was their own affair. After all, they didn’t need much, they were not used to luxuries…

Did he not provide a harvest home dinner and a joint of beef at Xmas.

Laura’s father was stonemason and as a skilled craftsman earned more money than the farm workers and so their home life was not as hard as some in Lark Rise. He could turn his hand to most things in stone but it was expected that each workman must keep to his own trade.

For thirty -five years he was employed by a firm of builders in the market town, walking three miles night and morning at first; cycling later. His hours were six in the morning to five in the afternoon.

He was not from Lark Rise, and some villagers thought him proud but tolerated him because of his wife, a local. He was Liberal in politics, and at election time he spoke about Gladstone’s polices which provoked laughter as he was an “amusing speaker”. He did have a major disagreement In Candleford with his wife’s uncle over Irish Home Rule which ended with him storming out of the house.

Children started work at an early age by our standards. Once girls had left compulsory schooling age the, there was pressure on them to get a place: they couldn’t earn money on the farms and the hamlet houses were overcrowded so arranging separate sleeping accommodation for sons and daughters was difficult. On the other hand, parents did not want their sons to leave home: their work contributed to the family income.

Young girls were sent off into service often at the age of eleven initially in the houses of tradesmen, school masters or bailiffs- certainly not public houses.

After a year the mothers began to say it was time they bettered themselves and the clergyman’s daughter was consulted… she could advertise in the Morning Post or the Church Times for situations for them. Other girls secured places through sisters or friends already serving in large establishments.

Once in service the daughters would regularly send money home – some half or even more of their wages.

The unselfish generosity of these poor girls was astonishing. It was said in the hamlet that some of them stripped themselves to help those at home.

The second book Over to Candleford describes different sorts of work. One of Laura’s uncles, Tom, was a small business man, making boots and shoes. His sign suggested a skilled craftsman

Ladies’ Boots and Shoes made to order. Best Materials. Perfect Workmanship. Fit Guaranteed. Ladies’ Hunting Boots a speciality… It was a common thing then for people of all classes, excepting the poorest to have their footwear made to measure

Tom employed several apprentices but he made the hunting boots and sewed the more delicate makes. The hunting ladies tried on their boots in the parlour. He visited Northampton twice a year to buy leather.

His family were more comfortably off: in their house there was piped water and an inside flush toilet unlike the wells and outside privies of Lark Rise.

Candleford Green was a separate village though later incorporated into Candleford. Laura’s mother had an old friend who lived there: Dorcas Lane, cousin Dorcas, as the children instructed to call her. She ran a wheelwright and blacksmith business left to her by her father, and was the postmistress. She did not work in the forge: she employed a foreman and workmen for that side of the business. She was an unusual woman:

She took in The Times and kept herself well-informed of what was going on in the world, especially in the way of invention and scientific discovery. Probably she was the only person on or around the Green who had heard the name of Darwin. Others of her interests were international relationships and what is now called big business

In a different era she could have thrived and made a name for herself but openings for women were rare in those days s she had to be content with Candleford Green

As was the custom at the time, the unmarried workmen lived in with their employer. They shared the same meals though class distinctions were maintained. Dorcas sat at the head of the table carving the meat, then there was reserved space for any visitors, then Matthew the foreman’s chair, then a further space to indicate the social difference between a foreman and ordinary workers. The three workmen sat in a row at the end of the table facing Dorcas.

The business of the forge was varied: shoeing horses, making hinges, gates & railings. However, the change in farming methods and the advent of the motor car led to changes in the business: motor repairs were added:

The legend over the door was repainted, Motor Expert

When Laura was thirteen there were questions over what she should do. Her mother had hoped she would follow in her footsteps and become a children’s nurse, but Laura was not cut out for that: she was nervous and clumsy with babies. Fortunately, Cousin Dorcas asked her parents if she could go to Candleford Green and learn Post Office work.

At the age of fourteen Laura moved to Candleford Green and started work in the post office. First however she had t sign a declaration before a magistrate that she would not interfere with the Royal Mail.

For the first few days Laura feared she would never learn her new duties. Even in that small country Post Office there was in use what seemed to her a bewildering number and variety of official forms, to all of which Miss Kane who loved to make a mystery of her work referred to by number, not name. But soon… AB/35; K21; X.Y.13 … became “The Blue Savings Bank Form; The Postal Order Abstract; The Cash Account Sheet.

She was daunted by the stamps and was nervous handling the higher value ones. As she had been good at arithmetic at school, the giving of change quickly became easy

The hours were long, starting at seven in the morning, finishing late at night with no half day off and work needing to be done on Sundays. There were compensations – the pace of life was more leisurely and there was always time for a chat with the customers. There were two woman letter carriers who did cross country deliveries. Later one of them, Mrs Macey, was called away by an emergency and Laura volunteered to do her delivery. This was a delight to her as she could do her deliveries quickly and then enjoy exploring the woods around the village. Fortunately for Laura, Mrs Macey had to move away so Laura took on her deliveries with an extra 4/- per week. She had to ask her parents’ permission first which was not automatically given: her father thought she would demean herself and get coarse and tomboyish, traipsing about the country”. Her mother worried that “people would think it funny”. However, they did consent as she was keen and Miss Lane had suggested it. A pair of stout shoes were ordered from Uncle Tom which lasted all Laura’s time as a postwoman!

I really enjoyed the book: the author describes the daily round of ordinary people’s lives in detail, never condescending. In fact, she seems to regret some of the changes. They may have made life more comfortable but something was being lost in the process. Her descriptions of the countryside, the woods and fields are lyrical.

The villagers of Lark Rise were poor but “Even the poor enjoyed a rough plenty”. They had a healthy diet (albeit rather monotonous) but most kept a pig and had an allotment to grow fruit and vegetables; there were always wild fruits to collect from hedgerows and mushrooms from the woods. The mothers made jams and cordials. The children thrived on the fresh air and they had the countryside to explore.

But, in spite of their poverty and the worry and anxiety attending it, they were not unhappy, and, though poor, there was nothing sordid about their lives.

It was a hard life, but the hamlet folks did not pity themselves. They kept their pity for those they thought really poor.

The children brought home from the Sunday School Lending Library books about the London slums which their mothers also read. Many tears were shed in the hamlet over Christie’s Old Organ and Froggy’s Little Brother, and everybody wished they could have brought those poor neglected slum children there and shared with them the best they had of everything.

Lark Rise first edition 1939.

Lark Rise first edition 1939.