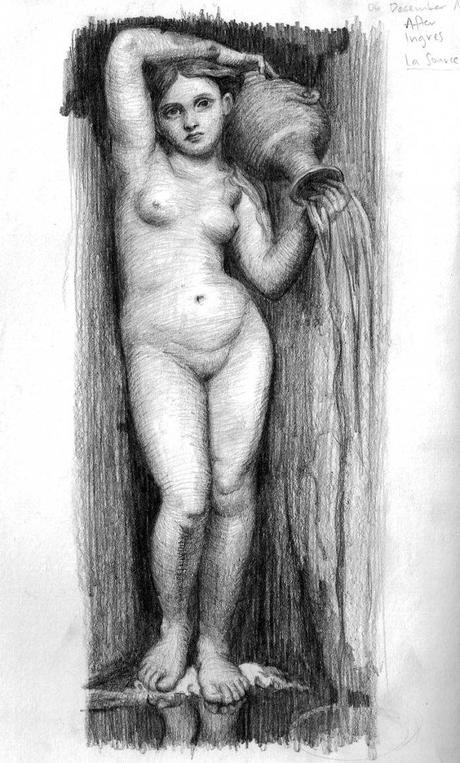

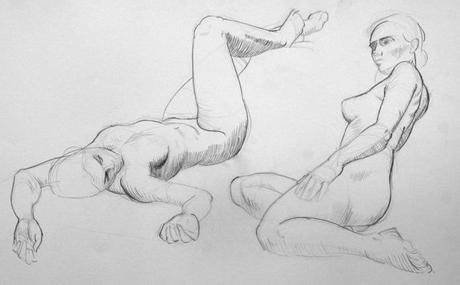

After Ingres, La Source

I have been thinking about how important it is to uncover one’s source. My dear friend Jacques has been in town, and his simultaneous lightness and solidity has been energizing. But it is not enough to rely on the buoyancy of others. I think of Ingres’ La Source, and of how she sustains herself: an endless spring, an infinite well needing no support.

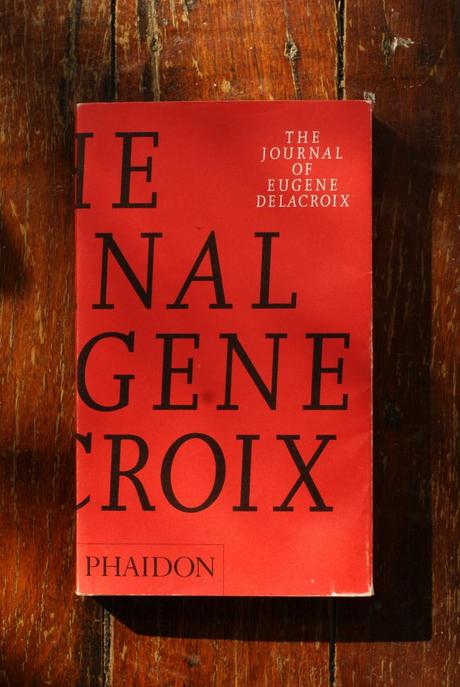

Delacroix (p. 32) struggles, early in his journals, with a restlessness—‘This restlessness that comes over me almost every evening! Oh sweet contentment of the philosophers, why can I not capture you?’ He concludes, ‘I must never put off for a better day something that I could enjoy doing now. What I have done cannot be taken from me.’ Knowing that you have invested your energies and your time into something meaningful allows you to sustain yourself—independent of others, independent of circumstances—able to carry yourself, and pick yourself up, and nourish yourself. Delacroix (p. 29) muses, ‘Even one task fulfilled at regular intervals in a man’s life can bring order into his life as a whole; everything else hinges upon it.’

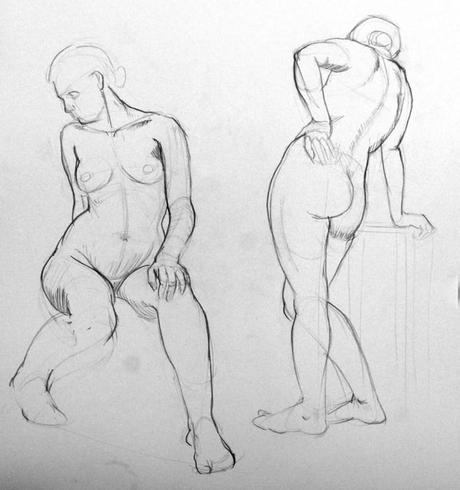

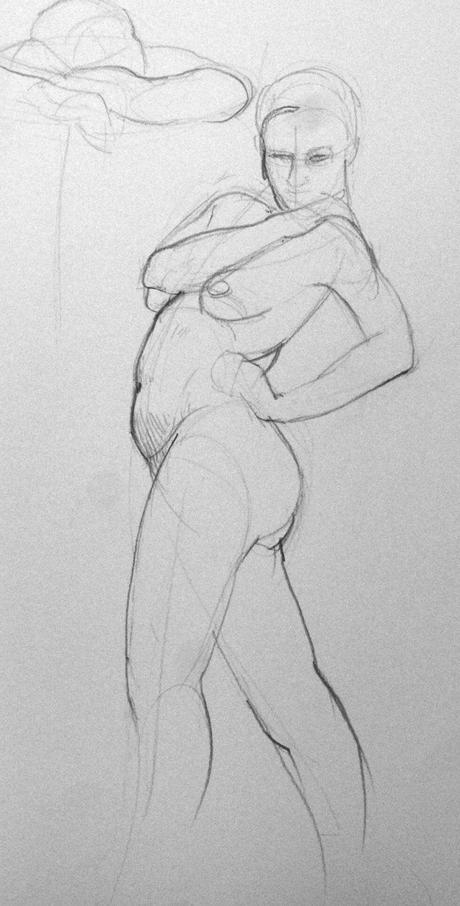

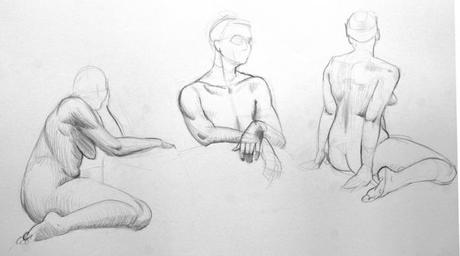

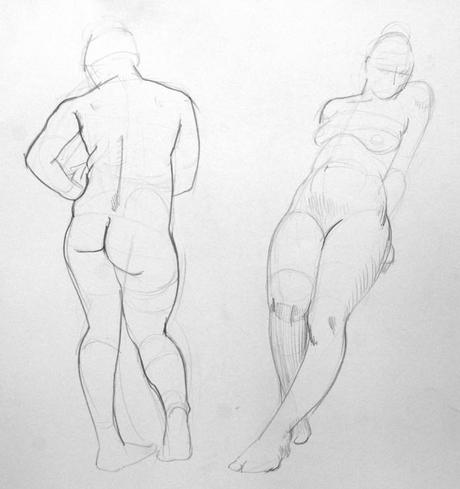

And so, I begin to look for the things that cut through everything else, the things I can return to, the things that I can build on day after day and thus build myself up. While Jacques is employed in a field of theoretical physics that keeps him wholly engaged and focused, thus finding a source in his work, I must fill the crevices left in my days with the things that energize me. Drawing stands out like a beacon. When I’m not drawing, it seems hard and important and worthy of time, too big and significant for snatches of moments. But once it slips into those snatches, it penetrates everything—bad moods, sadness, fatigue. I must depend upon my drawing. Philosophy, too—I remember the consolation it has given me, far deeper than any escapism offered by fiction. My quiet time over coffee, studying German, and practicing grammar, and gaining a mastery over something new and challenging. These things are solitary and unshakeable, and with them I can prop myself up, and build myself up. I must draw, and study, and think deeply, and I will be refreshed and strong enough to face the world.

Delacroix (p. 20) happened upon the same realisation: ‘Poor fellow!’ he chided himself. ‘How can you do great work when you are always having to rub shoulders with everything that is vulgar. Think of the great Michelangelo. Nourish yourself with grand and austere ideas of beauty that feed the soul. You are always being lured away by foolish distractions. Seek solitude. If your life is well ordered your health will not suffer.’

I am amazed that my sketchbook languishes when I know what it gives me! So few tools, and yet they give me the power to invert everything. It is like holding up a pitcher that never runs dry—what sorcery!

Later in life, Delacroix (p. 133) reflects on the source of his strength and peace, probing himself thus: ‘Why was it that I lived so fully on that particular day? Because I had a great many ideas that are miles away from me now. The secret of having no worries—at least where I am concerned—is to have plenty of ideas. Therefore I cannot afford to let slip any means of encouraging them. Good books have this effect, and especially certain books. Health is the first consideration, but even when one is feeling dull and tired these particular books can renew the source from which my imagination flows.’ Endlessly refreshed by Dante, and perpetually inspired by Rubens, Delacroix persevered with his work in spite of feeling ill, or tired, or distracted by companions. He struggled, but he knew himself well enough to bring himself through those struggles and focus on what was most meaningful to him—and, as we all hope to, to produce something enduring, the true offspring of that drive.

My friend and philosopher Mark muses, ‘I begin to suppose that life will never feel more real or more lively than it does right now, and if we ever want to do something great, we must do it feeling like this.’ I think he is correct in concluding that it won’t strike us like a bolt from the heavens, this energy that will propel us to greatness. He is right to feel we must push on through apathy. But if we can nurture that part of ourselves in secret, and find that quiet spring inside us, perhaps we can pull ourselves out of that foggy place by our own bootstraps.

James Dickey, to conclude:

You? I? What difference is there? We can all be saved

By a secret blooming. Now as I walk

The night and you walk with me we know simplicity

Is close to the source that sleeping men

Search for in their home-deep beds.

We know that the sun is away we know that the sun can be conquered

By moths, in blue home-town air.

(James L Dickey, The strength of fields)

Delacroix, Eugene. 2010 [1822-1863] The journal of Eugene Delacroix. Trans. Lucy Norton. Phaidon: London.