For the Criterion Blogathon

With the release of one of 2014's most uniquefilms, Wes Anderson's The Grand Budapest Hotel, came an avalanche of publicity. The influences on Anderson's much acclaimed and awarded bittersweet romp through a fictional between-the-wars Old Europe were widely scrutinized in the mainstream press for a time: German writer Stefan Zweig (1881 - 1942), whose autobiography The World of Yesterday was a core inspiration; German-born filmmaker Ernst Lubitsch, who made a string of enchanting films of great charm and sophistication through the '30s and '40s; Grand Hotel (1932), Edmund Goulding's lavish Oscar winner for MGM; and Max Ophuls, another German-born filmmaker, whose elegantworks were marked by deep wit, a cosmopolitan world view and an affinity for Old Europewhich he depicted on screen with great style and tendresse many times Ophuls's Letter From an Unknown Woman (1948) is arguably the greatest film adaptation of Stefan Zweig'swork and, more directly linking Ophuls to The Grand Budapest Hotel, the name of Tilda Swinton's character, "Madame D," is a nod to the Ophulsmasterpiece, The Earrings of Madame de... (1953), the filmWes Anderson named first on his "top ten" list of Criterion Collection titles.

Max Ophuls

Born in 1902 in the Saar, a German state bordering France, Ophuls began as a stage actor. He moved to directing in 1923,staged more than 200 plays and became a leading theater director in Vienna before entering film in 1930. Liebelei (1932), Ophuls's film adaptation of a popular Arthur Schnitzler play, augured themes and a distinctive style that would become the hallmarks of his later work. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Ophuls, who like Zweig, Lubitsch and Schnitzler was Jewish, fled to France, where he became a citizen and continued to make films outside Germany for several years. He was forced to leave France with the German invasion and, in 1941, came to Hollywood, the last of Europe's emigre filmmakers to arrive. It was a difficult transition; his work was relatively unknown in the film capital and his singular style and approach to production were at odds with the studio practice of making movies factory-style with the emphasis on efficiency rather than artistry

Joan Fontaine, Louis Jourdan in Letter From an Unknown Woman

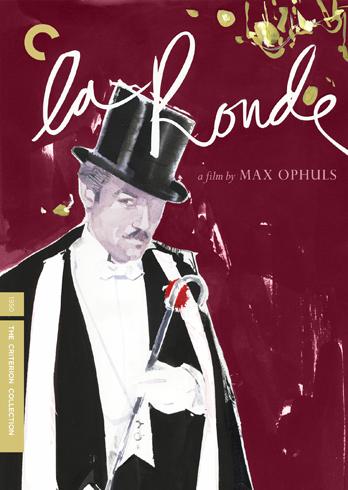

Writer/director Preston Sturges, who had admired Liebelei, eventually hired Ophuls to direct Vendetta, a film to be produced by Cal-Pix, an independent production company managed by Sturges and financed by Howard Hughes. Sometime well after principal photography began, Hughes insisted that Ophuls be fired because, according to Sturges, "he didn't like foreigners and didn't want any of them working for the company." Vendetta was shelved only to be re-written and re-shot after Cal-Pix was dissolved. However, industry word of mouth about his work on the unfinished Vendetta was strong enough to bring Ophuls more offers to direct and he would go on to make four films in America: The Exile (1947), the exquisite Letter From an Unknown Woman in 1949, and two films noir, Caught (1949) and The Reckless Moment (1949). Then he returned to France.Among the works of German playwright Arthur Schnitzler, author ofLeibelie, was the notorious Reigen ("Round Dance"), described by its authoras "a series of scenes which are totally unprintable," thoughit was privately printedand then published in 1903. Reigen was first performed years after it was written but, even with the passage of time, the play provokeda public scandal, riots, criminal prosecution and, later still, was banned. The film that would herald the return of Max Ophuls to the French cinema was his adaptation of Reigen, some thirty years after it debuted on the Vienna stage, titled La Ronde (1950).

Anton Walbrook and Simone Signoret as the carousel begins to turn in La Ronde

In his memoir The World of Yesterday (1942), Stefan Zweig chronicled a lighthearted, voluptuous fin de siecle Vienna where indulgence in fine food, wine, entertainment and the arts was an essential part of life. The Viennese, he wrote, enjoyed all that was stimulating, musical and festive and delighted in "theatrical spectacle as a playful reflection of life whether on the stage or in real space and time." It is in this spirit that Max Ophuls recreated and brought Old Vienna to life in La Ronde, a theatrical spectacle by design in which romance is ephemeral but passion is eternal.

Simone Simon and Daniel Gelin, a maid and a young man

Through ten interconnected vignettes, La Ronde follows a series of seductions. Each episode (with one exception) observes a romantic dalliance that links to the next when one of the lovers moves on. A recurring merry-go-round motif and Oscar Straus's waltz theme underscore the narrative's cyclic pattern. Straus'smelody, by turns merry, nostalgic or melancholy, weaves through the film reflecting mood and tone - and cuing the lovemaking about to begin or coming to an end. The rhythm built into the film's structure provided Ophuls with an ideal opportunity to explore his affinity for and mastery of camera movement, and La Ronde is a dazzling showcase for his breathtaking tracking shots and virtuoso camera work. The combined effect of rotating stories and characters and a camera ever in motion conjures a dance, a perfectly synchronized and choreographed Viennese waltz.

Daniel Gelin and Danielle Darrieux, a young man and a married woman

La Ronde's "dancers" were some of the great lights of mid-century European cinema: both new and established stars of France including Simone Signoret, Simone Simon, Daniel Gelin, Danielle Darrieux, Fernand Gravey, Odette Joyeux, Jean-Louis Barrault and Gerard Philipe, along with Isa Miranda of Italy and Anton Walbrook of Austria. No one in this all-star cast disappoints but many shine: Simone Simon, never more seductive, and Daniel Gelin as "The Maid and the Young Man," Gelin and elegant Danielle Darrieux as "The Young Man and the Married Woman," Fernand Gravey and Odette Joyeux as "The Husband and the Young Girl," Isa Miranda and Gerard Philipe as "The Actress and the Count." Best of all, underpinning the tone and linking each of the episodes, is Anton Walbrook as the urbane "Meneur de jeu" (ringmaster/host/puppetmaster), a pivotal character created by Ophuls for the film

Anton Walbrook, as the Meneur de jeu, assists La Ronde's censors

Walbrook introduces La Ronde dressed in modern clothing as he stands near a stage on a film set. In a long tracking shot, he crosses the set and, with the comment "Let's change our costume," dons the evening attire and top hat of another era, Vienna1900. Straus's waltz begins and Walbrook strolls to a carousel where Simone Signoret, a lady of the night, appears.From this point, his character will take many forms - often breaking the fourth wall - ushering in individual vignettes, taking an active role in some, commenting on the action, consoling the characters when a quickened pulse has led to a bruised heart. His is a wry, worldly presence with more than a suggestion of refined modesty, "I make fun of no one," he assures Simone Signoret's character.

Gerard Philipe as the count at table with his ever-present companion

La Ronde was a resounding popular success and launched the final, golden era of Max Ophuls' film career; Le Plaisir (1952), The Earrings of Madame de... (1953) and Lola Montes (1955), all made in France and all classics, would follow. These four films would be Ophuls's last; he passed away at age 54 in March 1957 of rheumatic heart disease.

All four of the final works of Max Ophuls are part of the Criterion Collection

In January 1954, Francois Truffaut published an article in Cahiers du Cinema, "Une certaine tendance du cinema francaise" (A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema) in which he championed a cinema d'auteur over what he viewed as a too traditional French cinema and mentioned a few of those he considered authentic auteurs; Max Ophuls is listed along with Renoir, Cocteau, Bresson and others. Appreciation for Ophuls's films extended beyond the borders of France and the shores of Europe. Among U.S. filmmakers especially influenced by his work were Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Kubrick. Today, a newer generation of American filmmakers has discovered Ophuls; Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson (There Will Be Blood, Magnolia) and Todd Haynes (Far From Heaven, I'm Not There) are among those who have gone on record with their admiration of his work.

~

This post is my contribution to the Criterion Blogathon hosted by Criterion Blues, Speakeasy and Silver Screenings. Click here for more information and links to participating blogs.

~Credits:

A film byMax Ophuls

Based on a play by Arthur Schnitzler

Adaptation by Jacques Natanson and Max Ophuls

Dialogue byJacques Natanson

Music byOscar Straus

Director of photography, Christian Matras

Sets byJean d'Eaubonne, assisted by Alfred Marpaux and Marc Frederix

Costumes byGeorges Annenkov

Editor, Leonide Azar

References:

The World of Yesterday by Stefan Zweig (1942) translation by Anthea Bell (Pushkin Press, 2009; University of Nebraska Press, 2013)

Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges: His Life in His Words, adapted and edited by Sandy Sturges (Simon and Schuster, 1990)

Stanley Kubrick: A Biography, by Vincent LoBrutto (Donald I. Fine Books, 1997)

Vincente Minnelli: Hollywood's Dark Dreamer by Emanuel Levy (St. Martin's Press, 2009)