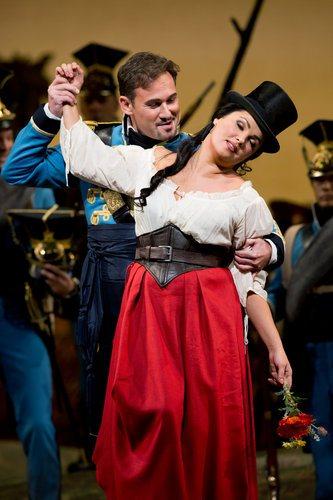

Ambrogio Maestri in L’Elisir d’Amore (Sara Krulwich/NY Times)

Opera, by its very nature, is tragic. Blame the ancient Greeks, who were credited with “inventing” what we usually refer to as tragedy. They’re also responsible for the farcical side of things, bless their Aegean hearts. Thank goodness for comic opera, I say, which helps to dissipate some of the gloom surrounding the more tragic variety.

One of the ways this was done is rather formulaic but no less effective: the use of the proverbial love potion, which has become a favored tool of composers from time immemorial. It’s no coincidence, then, that the fanatical German genius Wagner based an entire work on the damaging effects a love potion can have on a doomed couple named Tristan and Isolde.

Their story turns up in the least likely of places, most notably Gaetano Donizetti’s two-act comedy L’Elisir d’Amore, or “The Elixir of Love,” performed on opening night, October 1, 2012, at the Metropolitan Opera and rebroadcast in the Live in HD series on February 1, 2013, in director Bartlett Sher’s spanking new production. Coincidentally, Gioachino Rossini’s rarely heard Le Comte Ory, another Bartlett Sher creation, was scheduled for broadcast that Saturday afternoon, on February 2. Still another obscure item, Puccini’s melodious La Rondine, was given a radio hearing the previous January 26. It’s been a busy few weeks for the Met, hasn’t it? So let’s dive right in and get those reviews out!

But first, some background. Donizetti, in my subjective appraisal, was incapable of writing a true comedic showpiece. There, I said it. Now, you may disagree with that statement, but let me first make my case: compare his operas with those of, say, a contemporary such as Rossini. While Rossini admittedly had an all-around sunnier disposition and attitude towards life, reflected in his pleasingly varied output (The Barber of Seville, La Cenerentola, The Italian Girl in Algiers, Il Turco in Italia) and those endlessly inventive overtures, Donizetti was of a more sober nature. This sobriety was probably caused by the early death of his wife and three children, added to that a syphilitic condition aggravated by debilitating bouts of insanity – in themselves, a most pitiable state.

But just for argument’s sake, let’s take a brief look at two of Donizetti’s most amusing pieces, Don Pasquale and L’Elisir d’Amore. Both these sublime compositions feature moments of pure pathos (Norina’s slapping of the much older Pasquale; Adina shedding a tear over the love-struck Nemorino’s actions), tossed in amid the buffo elements. How curious that these sudden flashes of humanity are nowhere to be found in Rossini. There’s no question Donizetti was a master craftsman. In fact, I could go on and on about this or that aspect of his art, but suffice it to say that slapstick and the general mayhem that surrounded it was not in this composer’s blood. Advantage: Rossini.

Even still, let it be said that Rossini’s own operatic tragedies, as competently written as they often tended to be, could not possibly scale the dramatic heights that his rival’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Anna Bolena, Maria Stuarda, La Favorita or Lucrezia Borgia have reached. Match point: Donizetti.

Love that Elixir

One should be grateful for small favors. I say this in light of director Bartlett Sher’s latest concoction, a scenically splendid new version of L’Elisir d’Amore. I caught the HD broadcast of February 1 on my local public television station, which starred the ever-popular Russian soprano Anna Netrebko as Adina, American tenor Matthew Polenzani as Nemorino, Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien as Sgt. Belcore, and debuting baritone Ambrogio Maestri as Dr. Dulcamara, purveyor of the aforementioned elixir. The performance was led by maestro Maurizio Benini.

Anna Netrebko & Matthew Polenzani (Ken Howard)

For an Italian comic opera, there were only two such individuals in the cast, Maestri and Benini. Nevertheless, this was as refreshing a take on the old tale as any I’ve seen or heard in many a year. I was a bit skeptical at first of Polenzani’s Nemorino, here shown as a shy, bookish poet (a variation on the usual country-bumpkin approach to the part). Certainly, the roly-poly Luciano Pavarotti in his prime, and in the guise of a human Pillsbury Doughboy, practically owned this role on stage. No other tenor in recent memory – not Nicolai Gedda, not Roberto Alagna, and not even the highly enjoyable Rolando Villazon – could hold a candle (or wine bottle) to Luciano’s masterful interpretation. So identified was he with the part that I have a very difficult time accepting anyone else in it.

I will say this, though: Polenzani gave it his considerable all. That he simply could not fully erase memories of the great Pavarotti was not entirely his fault. As it was, he displayed fine vocal form throughout, and used his gorgeously supple instrument wisely and well, never forcing for volume or pushing for effect. It took a while for Polenzani to own up to the challenge, but after a most satisfying “Una furtiva lagrima,” with its prolonged ovation and steady stream of bravos, I was almost convinced we had witnessed the birth of a new tenor sensation. Time will tell if I’m proven right.

Polenzani has already received rave reviews for his vigorous performances in Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann (a vocal torture test for any tenor) as well as in Massenet’s Werther (another lovesick poet, albeit one who ends his suffering by shooting himself in the chest). Here, the tight close-up of his face, as he ruminated on the possibility that Adina, who’s been playing hard to get all along, was in love with him from the start, were marvelous to behold. The infinite variety of facial expressions Polenzani employed – all captured by the high-definition camerawork – are what HD transmissions are about and where they can be most effective: at home and in neighborhood movie theaters. But I doubt anyone past the fourth or fifth row could have hoped to see them, even with high-powered lenses.

The real star of the show, however, was the top-hatted Anna Netrebko. I say that will all due respect, for she is the Met’s main attraction, the best singing actress General Manager Peter Gelb has had in quite some time. What charm, what verve, what comic timing, and what fun she has on that huge stage! Her facial cues were just as impressive as Polenzani’s (and she was a lot prettier, too). Her voice has grown in size and substance since giving birth a few years ago (it’s also gotten darker and more expressive), although her diction remains problematic. She could be singing in Polish, for all we know. But who cares? Anna was charming and lively, which is about the best one can say for this part.

Nowadays, Netrebko’s what you might call a “full-figured” girl. That didn’t stop her from romping about the stage with abandon, much as Pavarotti used to do in this piece. Her best moment came when she finally admitted her love for the clueless Nemorino. As they both jumped into each other’s arms and fell helplessly to the ground (in order to take a brief tumble in the tall grass!), the audience burst into applause, a most winning episode.

Mariusz Kwiecien & Anna Netrebko (Sara Krulwich/NY Times)

They were interrupted by Mariusz Kwiecien, the boastful Sgt. Belcore. The role is a shallow one, both vocally and histrionically. It lacks a fiery romanza for the baritone to dig into, and in this production the soldiers were rather too harsh — some would say brutal — in their treatment of Nemorino and the villagers. Undeterred by what usually is portrayed as a minor character by second-rate leads, Kwiecien soldiered on. Boasting drop-dead looks, a brilliant tone, and, best of all, macho swagger to burn, Mariusz sang up a storm.

It’s a shame this role offered so little for him to hang his hat on. Fortunately, he’s been seen in several new productions, including last year’s Don Giovanni, as well as two others, Don Pasquale and Lucia – the latter two co-starring Anna Netrebko. This is a fine working relationship. Both singers have known each other for years and, to top it off, react well to each others’ presence. Let’s hope we never run out of operas for them to appear in – they make a great team together. (Note: they are scheduled to sing in next year’s Eugene Onegin).

On the lower-voiced end, there was the debuting Ambrogio Maestri as Dulcamara. A giant of a man (he towered a full head over everyone else), Maestri looked like a cardboard cutout of the late stand-up comedian Marty (“Hello, dere”) Allen. His rotund form helped to “fill out” the role’s comic proportions, and his Act I patter song, “Udite, udite, o rustici,” was perfectly executed, with well-nigh impeccable diction and well-timed delivery. His large voice easily filled the theater. I’m sure his illustrious predecessors, the great Salvatore Baccaloni, Fernando Corena (who I saw in The Italian Girl in Algiers back in 1975 at the Met), Paolo Montarsolo, and Renato Capecchi would be proud.

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes