Iam amazed by naive English goalfests, I admit it. And what alternative does a man so cornered have but to try and write about it in a post that should itself look like a shot-at-goal—a shot which, in a silent movie, would be visible as a puff of smoke. It is in this moment, a flickering light about to be extinguished, that Manchester City seems to play: not ridiculous by all means, nor necessarily feeble, but freely as in a circus or a street procession. It’s not that Balotelli tries to act like a fashion-bomb, it’s just that his style fits an elegant swordsman coming down from Prague to Desenzano riding a two-horse carriage. City’s football is at times sloppy, as though they knew already that at some point they’re going to score; otherwise it is a charivari of cacophonies, as when Jacques Offenbach traveled to America (and the French impresario did well by choosing the trumpet to represent the country in a new waltz he composed and offered to his hosts). It is a linguistic contortion of the kind attempted by Tom Waits in “Kommienezuspadt,” a track of the 2002 album Alice which is the perfect and uncanny companion when you’re sitting silent in a pub, mesto e taciturno, and the soaked glass of your beer shines almost as bright as polished onyx.

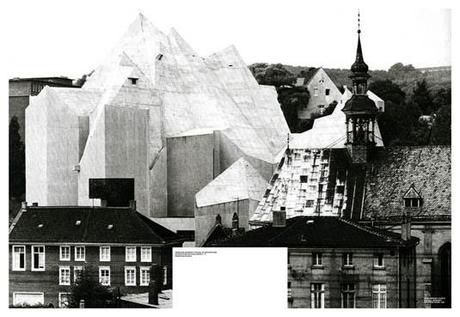

Against a toothless Blackburn side, Yaya Tourè, somewhat awkwardly, hurried his steps in the customary midfield silence, like a water prince the day following the mermaid’s departure. What distinguished the outline of Mancini’s team from the equivocal parade of goals that had once inspired the amiable hymn of “Rule, Britannia” is, quite simply, nonchalance. Take United, the other half of Manchester. Every winger is playing on the wrong side now; Ashley Young trails last-minute crosses with the weaker foot only for Giggs, picked up like the Queen in a deck of tarot cards, to score with the weaker foot and his shoulders almost against the goal. But Kolarov here was curling the ball to the very limits of the game, straight as an archer, and compared to the beginning of the season, everything at Manchester City has become almost invisible, smoothed over. Aguero brought real substance in a mood that was curiously subdued, like a monosyllabic meeting at tea time, while Dzeko’s goal was executed with a soundless precision—he still carries with himself the joy of the townspeople gathering at a market square, but now you see the architectures of his towering header inside the land-plan. ♦