Photo by John Llewelyn

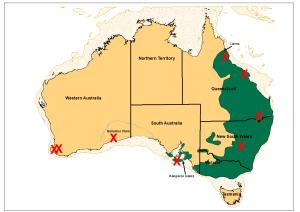

Koalas are one of the most recognised symbols of Australian wildlife. But the tree-living marsupial koala is not doing well throughout much of its range in eastern Australia. Ranging as far north as Cairns in Queensland, to as far west as Kangaroo Island in South Australia, the koala’s biggest threats today are undeniably deforestation, road kill, dog attacks, disease, and climate change.

With increasing drought, heatwaves, and fire intensity and frequency arising from the climate emergency, it is likely that koala populations and habitats will continue to decline throughout most of their current range.

But what was the distribution of koalas before humans arrived in Australia? Were they always a zoological feature of only the eastern regions?

The answer is a resounding ‘no’ — the fossil record reveal a much more complicated story.

Green indicates the present distribution of koalas in Australia, and the red crosses indicate where koala fossils have been found.

While there are unfortunately not many koala fossils relative to many other Australian wildlife species (living or extinct), a few have been unearthed from which we can test hypotheses about how this species’ range has changed over the last few hundred thousand years.

Koala fossils dating to around 150,000 years ago have been found in south-western Western Australia, and others have even been found on the Nullarbor Plain.

This remarkably different distribution in what is — in geological terms anyway — the recent past, suggests that the eucalypt forests on which koalas rely for food and shelter must have had rather different distributions than they do today.

This led us to pose the following questions: Did the eucalypt forests characteristic of the relatively wet east and southeast of Australia cover a much broader range in the past than they do today? If so, did they extend across the Nullarbor and into Western Australia during at least some periods over the last few hundred thousand years?

In our paper just published online in Ecography, we address these very questions by using correlative species distribution models to predict the past distributions of 60 different trees (mostly Eucalyptus species) eaten by koalas today.

We applied these models based on the present distributions of koala-browse species to construct a set of environmental ‘rules’ that dictate where each species can grow. Using climate data such as temperature and rainfall, as well as soil data, we then applied these environmental rules to hindcasts of simulated past climates.

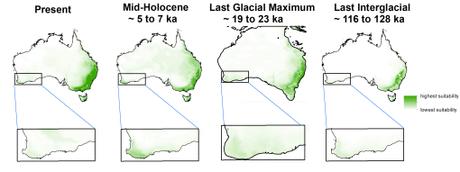

We reconstructed the most probable distribution of koala-suitable forests across the continent, looking at these distinct periods:

- during the Last Interglacial period from 128,000 to 116,000 years ago

- the Last Glacial Maximum from 23,000 to 19,000 years ago

- the Mid-Holocene between 7,000 and 5,000 years ago

As we had hypothesised, our models predicted a marked increase in the amount of suitable habitat for koalas between the Last Interglacial and the Last Glacial Maximum, followed by a rapid loss of forest extents up to the Mid-Holocene and to the present day.

Green indicates the distribution of koala food sources (edible eucalypts), whereas the white areas are where no suitable koala habitat is predicted. During the Last Glacial Maximum, Tasmania was connected to mainland Australia, and the coastal regions exceeded those of today given much lower sea levels at that time.

This waxing and waning of forests over these intervals therefore support our idea that coastal forests likely extended from the east through the Nullarbor, and into Western Australia. This would have been enough to allow koala populations to cover this entire region.

However, as the forests retracted eastward, they left only small populations of koalas in habitat refugia in the southwest, or disappeared entirely in the case of the Nullarbor.

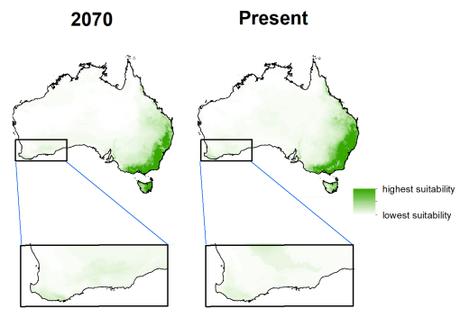

Green indicates the relative quality of predicted koala-food sources.

But we did not just look into the past, we also used the same approach to project the distribution of koala habitats to different periods in Australia’s future. And it’s not good news — our projections for 2070 confirm that this trend of retracting habitat is likely to continue.

Faced with all of the other threats koalas — and most other native Australian species — endure today, this might mean that we could lose the koala forever. But there is hope if do whatever it takes to protect existing koala habitats as well as replant those already destroyed.

—

Farzin Shabani, Corey Bradshaw, Frédérik Saltré, Katharina Peters, Antoine Champreux