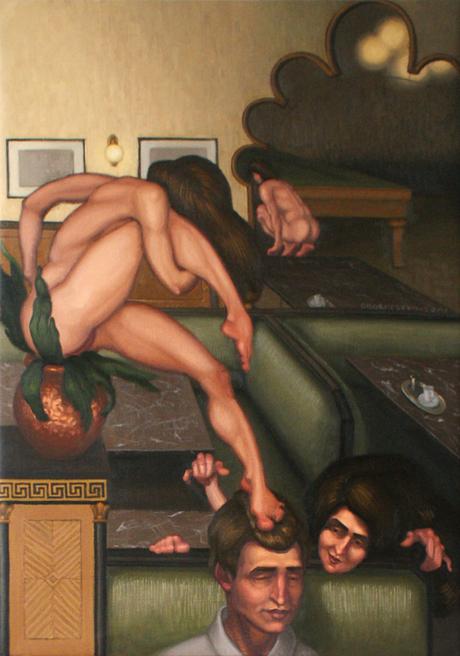

Coffee house muses (c) Samantha Groenestyn

Malcolm Budd (2012: 205) is not restrained in his admiration for Richard Wollheim’s (1987) influential book Painting as an Art, but he finds Wollheim’s appeal to a distinctive phenomenology by which we encounter paintings to be rather extravagant. Wollheim’s (1987: 22; 181) account of pictorial representation notoriously avoids language-driven accounts of representation, and turns squarely toward our experience of what it is like to look at a painting. Crucially, finds Wollheim, we exercise a remarkable ability (not exclusive to looking at paintings) to be aware of both the painted surface and of something depicted in it–at the same time. He calls this phenomenologically distinct feat ‘seeing-in.’ Budd (2012: 194) finds seeing-in to be inadequately described and unsupportable. What Wollheim cannot escape, he argues, is that our ability to grasp what a picture represents is inevitably grounded in knowledge. Proposing added visual experiences is a superfluous move when we inevitably need to secure representation by means of knowledge.

Wollheim introduces seeing-in between the perceptual experiences of ordinary seeing and illusion. Seeing, on its own, is a wonderfully complex process, but what has been traditionally difficult to account for is that a painting presents us with two very different objects of attention in the one object. The same marks may be seen as marks on a surface or as the scene or person they represent. This adds a layer of complexity to seeing that has proved difficult to reconcile. Ernst Gombrich (1959: 5) champions illusion as the solution, arguing that we do not see both surface and image at the same time, but that we are able to flick between the two visual experiences. When we attend to the image we submit to the illusion. Budd (2012: 187) clarifies that this by no means demands that we hold a false belief; rather, we are able to hover between two different perceptual experiences that have the same representational content. But what he finds unsatisfying about Gombrich’s solution is that it excludes the possibility that we can experience both at the same time.

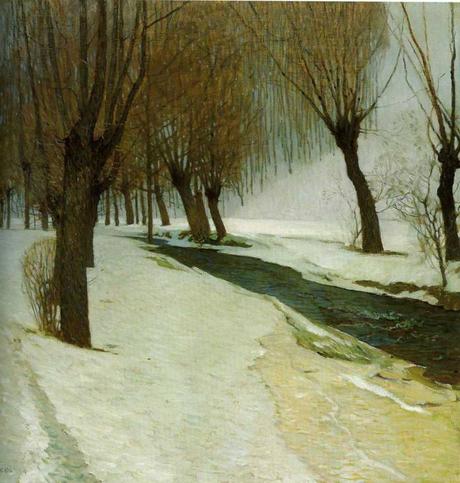

Wohnzimmer (c) Carl Moll (1903)

If we reflect on the experience of looking at paintings (the kind of thing a phenomenologist would do), it would indeed seem that we can attend to both surface and image at once. Gombrich’s insistence that one cannot seems stubbornly at odds with the experience of looking at a painting. Certainly, sometimes we are so caught up in the picture that we concentrate more on its content, but (aside from plausibly-located trompe l’oeils) we are not prone to mistake paintings for the thing that they depict, nor to really forget that they are paintings. Sometimes we are so enamoured of the paint that we neglect the content, but it is difficult to block out the content entirely. Perhaps the best counterargument to Gombrich is the kind of painting that proudly brandishes its physicality, of which countless fine examples abound. Let’s limit our examples to the Viennese painter Carl Moll. His naturalistic portrayals of Viennese interiors and parks and hills are recognisable scenes of breakfast settings and villages among forests. But their dappled marks of all manner of inflection, their tight design and their honest but somehow augmented colours are inescapable reminders that the object of our vision is a painting. The distortion is always just enough that the paint must always be present in our experience, even when contemplating a Wiener Frühstück.

Mutter und Kind am Tisch. (c) Carl Moll (1903)

Wollheim (1987: 46) begins to describe such experiences, echoing Leonardo da Vinci’s (2008: 173) example of the battles and landscapes to be found in textured walls by the daydreaming eye, but his appeal to phenomenology goes little further, argues Budd (2012: 194). By Budd’s estimation, the phenomenon remains under-described, and in any case, it is not clear that the step is at all necessary. At least one feature of the experience must be established: Budd (2012: 193) argues that seeing-in must involve distributed attention, a specifically non-focused attention that roams the picture as we take in the picture as a whole, or an attention rather meditatively shared among the many properties of a picture (a theme Bence Nanay (2016: 13; 21, 22) takes up with great enthusiasm). Without distributed attention, the perceptual experience simply lapses back into seeing (in which we see only paint) or gives way to illusion (in which we see only the image).

Rather than pursue the necessity of distributed attention, Budd recasts Wollheim’s earlier and later accounts of representation in terms of his own favoured emphasis on depiction. The choice is significant: depiction frames representation explicitly in terms of a referential relationship. It says that a picture refers to something else in the world which it depicts, for which it is in some way a substitute, without being equivalent, for the thing in the world does not ever depict the picture. This explanation insists that pictures are dependent on the world. Moreover, it operates in a very linguistic way, treating pictures (or their parts) rather like propositions that refer to objects or ideas. I am not too sympathetic to this attitude and neither is Wollheim. His explicit rejection of language-driven explanations makes his unconventional appeal to phenomenology unsurprising. It is clear that Budd persists in the propositional tradition of representation, but we shall examine his criticism nonetheless.

(c) Carl Moll

Depiction, he begins, demands an awareness of two things: both the marked surface and what is depicted (Budd, 2012: 186). When we are aware of both, we can correctly determine what a painting depicts. Were we not aware of the surface, we would think we were looking at the real thing. Were we not aware of what is depicted, representation would break down and we would be left with an incomprehensible arrangement of paint. Traditionally, work on representation tries to relate these two kinds of awareness, but the real problem, explains Budd (2012: 186), was always a knowledge-based one. The awareness of what is depicted is comprised of two parts: that we can see that x is depicted, and that we know what an x is in order to recognize it. Representation, when it succeeds, hangs on this knowing what before any concern about perceptual experiences. For a spectator to see a representation of snow, he must first know what snow is, then see that there is snow in the picture, and finally see that the picture is on a surface and is hence a picture and not actually snow.

Winter in Preibach (c) Carl Moll (1904)

Wollheim describes his special perceptual capacity, on which seeing-in is based, in two different ways as his theory develops. The early version describes it as two simultaneous experiences; the later version describes it as a single experience with two aspects. Budd treats each version in turn. The early stance states that seeing-in is based on a special perceptual capacity that involves simultaneously seeing two things: one that is present before the eyes and one that is not. The paint (or the rough texture of the wall) is what is directly visually perceived; the snow is also visually perceived but it is not there. Seeing what is not there, by Wollheim’s account, is a ‘cultivated experience,’ and here, argues Budd (2012: 196) lies the gap that Wollheim cannot fill perceptually. Wollheim can see that there is snow, but must bring his knowledge of what snow is to the picture. The what is hidden beneath the that.

Wollheim’s later account simply buries the problem even deeper, Budd (2012: 199) continues. In merging the two experiences into a single perceptual experience, twofoldness, with two aspects, a configurational and a recognitional aspect, Wollheim neglects to explain from whence this recognition arises, if not from some prior knowledge. The gap, the epistemic blank, reemerges in this subordinate part of the unified perceptual experience.

Let us examine this knowledge gap. For Wollheim (1987: 44; 89), it is crucial that all the resources that a spectator needs to engage with a painting are contained within that painting. This is because he wants to locate the meaning of a painting within itself, rather than use the painting as a tool for getting at the meaning of the world. The latter kind of position, held by proponents of symbol-driven theories like Nelson Goodman (1977: 241; 260; 265), see the painting and its elements as substitutions for concepts or objects in the world, as something that must always be interpreted in relation to the world. To ascribe a painting this kind of placeholder-status is to treat it propositionally: like language. Wollheim knows that we bring our own preconceptions to a painting, and he does not utterly discredit this type of meaning. But, he argues, it is not the most illuminating nor the primary type of meaning that paintings can have (Wollheim, 1987: 22). Indeed, we can engage meaningfully with a painting in spite of a lack in our knowledge.

At the sideboard (c) Carl Moll 1903

Consider a painter, perhaps from Australia, who has never seen snow. She has, however, seen paintings of snow, and has heard a few things about it. Everything she knows about snow has been gained from second-hand sources. Nevertheless, she may go on to convincingly paint a snowy picture that conveys the unmistakable airy softness of thick, freshly-fallen snow, its icy sparkle in the sun, its mellow blueness in the shade. This knowledge of what snow is seems very mysterious for it was gained through knowledge that certain pictures represent snow. Budd’s knowledge requirement is not as primary as he claims. The same might be argued for mythical creatures, of which we become acquainted through fabricated pictures. Importantly, it seems that this knowledge stems from perception in one way or another: sometimes perception of the world, of snow itself; sometimes perception of other pictures.

Nanay (2016: 51) directs us back to perception for an explanation of this knowledge gap. He adds some nuance to Wollheim’s twofoldness by extending it into ‘threefoldness’ (Nanay, 2016: 48). Not unlike Budd, he distinguishes between three aspects, with the crucial difference that he considers each of them to be accessed by a perceptual experience. He lists them thus:

A: the two-dimensional picture surface

B: the three-dimensional object the picture surface visually encodes

C: the three-dimensional depicted object

Like Budd, Nanay distinguishes between the that and the what: B is the painted snow, and C is snow in the world, or the village of Nußdorf itself, to return to Carl Moll. For representation to succeed, by Nanay’s (2016: 58) account, we only need to perceive A and B, not A and C. The unfortunate Australian painter who has never seen snow, and those unfamiliar with Vienna’s delightful circle of wine-producing hills, can still successfully identify these in pictures. But more than this: without any idea where Nußdorf is or what it looks like, a spectator can still see a well-defined if anonymous village replete with church spire in the picture. The picture is not wholly without meaning simply because the spectator cannot put a name to it or connect it to a referent in the world. Similarly, a picture of a person can be recognised as such and even quite arresting even if that person remains anonymous to us.

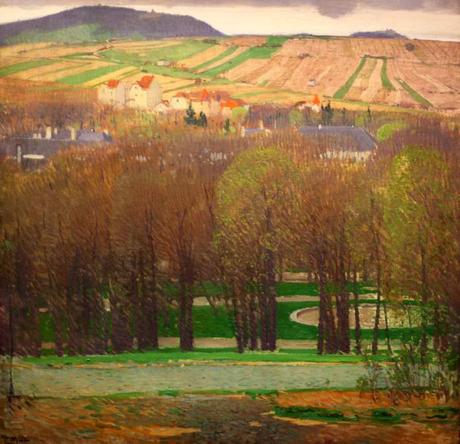

Blick über Nußdorf und Heiligenstadt (c) Carl Moll

Nanay (2016: 55) describes this knowledge-deficiency in terms of perception. To the spectator uninitiated in the wine- and wandering-oriented recreation offered by the Viennese hills, C (Nußdorf itself) remains both unperceived and unrepresented. For the Viennese who does recognize those particular hills, Nußdorf is represented, though not immediately before his eyes. The final step, explains Nanay (2016: 55) is this: while gazing upon the hushed horizon of the painting, Nußdorf itself is ‘quasi-perceptually represented.’ The two experiences of seeing (one of what is there: the paint; one of what is not there: Nußdorf) comprise two simultaneous perceptual states and their overlap, says Nanay (2016: 57), is what the distinct phenomenology of recognising what a picture represents amounts to. Recognition is not necessary for representation to succeed, but when it does occur Nanay argues that it is possible to account for it perceptually.

Not so for Budd (2012: 204), who insists that ‘whatever a picture depicts, you would not see it as a depiction of that thing if you were unaware of what that thing looks like from the point of view from which it has been depicted.’ Representation completely falls apart for him when the unlucky spectator has a particular gap in his knowledge. And yet, the hazy scene through Nußdorf and Heiligenstadt and on to the hills retains its representational charm, not dissolving entirely into a completely impenetrable textured abstraction. Representation proves more robust than this.

View on the Nussberg toward Heiligenstadt (c) Carl Moll (1905)

Indeed, should the uninitiated spectator succumb to the lure of the hills that Moll irresistibly conveys and travel to Vienna, he might gaze out at the real thing and note with some amazement that hills do in fact possess certain qualities that he gathered from the paintings. That sometimes they are a deep, violet-blue with crisp edges, and other times they dissolve, pale and silvery, into a husky purple sky. Something of the sleepy wine-drenched atmosphere soaks the pictures in a way that is more honest than the real thing, and not entirely absent from the real thing.

Budd considers it an unjustifiable extravagance to turn to phenomenology and posit a new species of seeing. As we have considered, his account of representation remains rooted in language, and reexamining the experience of looking at a painting is an attractive alternative if one finds this kind of substitution-based interpretive meaning inadequate when it comes to painting. I would suggest that Wollheim’s move is far from extravagant, and could be extended further. Looking at a painting, at its variegated surface and its carefully conceived relationships, is very different from looking at whatever it ‘depicts,’ and not only because of the mysteriousness of seeing the three-dimensional in the two-dimensional. It is as though one is granted access to the perceptual experience of another, the artist. The artist is able to show far more about her perceptual experience by her deliberate selection, construction, augmentation and handling of the what. She is able to show something of how she experiences the hills, tinged with memory and longing, spiked with intense heat or blistering cold, as a solitary thinker or basking in delightful company. Painting, by its very nature, offers us perceptual experiences far beyond our ordinary visual encounters, specifically by merging it with the horizonal structures encountered by others: painters.

Obersdorf

Budd, Malcolm. 2012. Aesthetic Essays. Oxford University: Oxford.

Gombrich, Ernst. 1959. Art and Illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation. Phaidon: London.

Goodman, Nelson. 1976. Languages of Art: An approach to a theory of symbols. Hackett: Indianapolis.

Nanay, Bence. 2016. Aesthetics as Philosophy of Perception. Oxford University: Oxford.

Wollheim, Richard. 1987. Painting as an art. Thames and Hudson: London.

Da Vinci, Leonardo. 2008 [1952]. Notebooks. Oxford: Oxford.