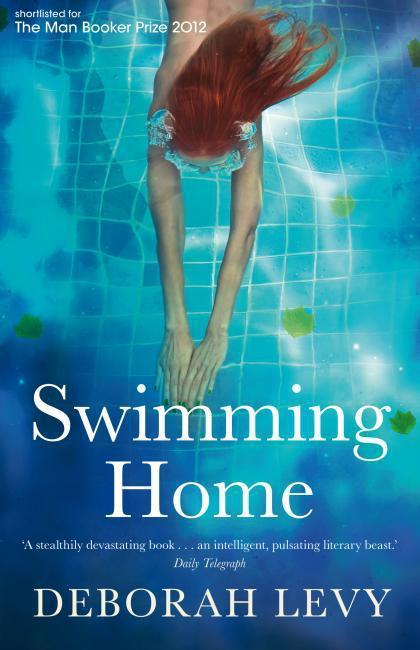

Swimming Home, by Deborah Levy

One of the weird things with fiction is how even the most tired of ideas can work in the right hands. In Swimming Home Levy writes about a group of middle class Brits on holiday in the South of France, and how the introduction of an ambiguous newcomer brings out all the tensions that were simmering below their comfortable surface. Put like that, it sounds awful. As ever though, it’s the writing that matters. Levy had me from the first sentence:

When Kitty Finch took her hand off the steering wheel and told him she loved him, he no longer knew if she was threatening him or having a conversation.

Joe Jacobs is a famous poet who draws on his past as a Jewish exile who fled Nazi-occupied Poland as a child. Before he was Joe he was Josef; to his readers he’s JHJ; to family friend Mitchell he’s the “arsehole poet”. His several names reflect his own act of self-creation.

Isabel, Joe’s wife, is perhaps more famous still. She’s a highly regarded war correspondent; cool under pressure. Isabel knows that Joe is repeatedly unfaithful to her; how she feels about that is less clear.

Staying with Joe and Isabel is their 14-year-old daughter, Nina, and friends Mitchell and Laura who own a shop together selling exotic knickknacks. Mitchell is an obsese glutton who has lately taken to hunting with antique guns, some of them clearly Chekhovian. His twin passions are consumption and extinction. Like Isabel, Laura is a loyal wife let down by an errant husband, but Mitchell’s indiscretions are financial rather than sexual and their business is teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

Into this uneasy mix comes Kitty Finch, human catalyst, found floating face down in the villa’s swimming pool which is “more like a pond than the languid blue pools in holiday brochures.” Her hair splayed out around her, at first they wonder if she might be a bear. It would be better for them if she were.

The setup is pretty conventional. The execution isn’t. Swimming Home is an uncertain text, fluid and Freudian and brimming with sex and death. Kitty claims to be the victim of a mistaken double booking of the villa, but that’s fairly obviously untrue. Even so, Isabel offers her a spare room, a curious act given Joe’s history with available young women. Isabel is seen by others as controlling, by giving space to Kitty is she relinquishing control or is this some form of extension of it?

Kitty is thin and intense. She’s prone to standing around naked at times of stress, a distracting habit but one everyone rather puts up with. She has a history of depression, but then so does Joe – it’s something they have in common. She becomes the whirlpool around which they all spin, even the supporting characters: the villa’s hapless caretaker Jurgen who is besotted with her and the elderly next door neighbor Madeleine who is convinced that Kitty is distinctly dangerous. Kitty is a catalyst. Her nudity and youth suggest sex, but her skeletal frame suggests a different kind of annihilation.

Kitty’s presence isn’t an accident. She’s there for Joe, because she writes her own poems and she tells him that she writes every one of them for him. She’s an obsessed fan, and naturally she’s brought a poem of her own for him to read. This happens to him a lot, but if he wants her body the least he can do is read her poem even if he would much prefer not to. Levy shows a wry sense of humor here, though disquiet is never far away:

‘Why are you shaking?’ He could smell chlorine in her hair. ‘Yeah. I’ve stopped taking my pills so my hands are a bit shaky.’ Kitty moved a little nearer him. He wasn’t too sure what to make of this until he saw she was avoiding a line of red ants crawling under her calves.

The narrative switches perspective between the various characters, not all of whom are equally well developed. Joe and Kitty obviously stand out, as does Isabel caught as she is between the expectations of her role as wife and mother and her exposure to the horrors of the world. Laura, 6’3″, is uncomfortable in her own body but otherwise it’s fair to say she doesn’t get anything like the development Joe, Isabel, Kitty and Nina do (even if Nina’s voice sometimes felt a little young for a 14-year-old to me). Even less so does Mitchell, who comes dangerously close at times to one-dimensionality.

Although Swimming Home is a short book, it’s a dense one and it’s not a particularly quick read. It’s often dreamlike, filled with fragmentary repetitions and foreshadowings. Like Greek drama it unfolds according to its own inexorable logic, not always as we would expect it but with the inevitability of hindsight. It brings in to the mix the burden of history (Joe’s past and Isabel’s reporting), art and literature (Joe), commerce (Laura and Mitchell), marriage, sex, old loves and new ones. It’s a rich brew and while I’ve only read it once I have a suspicion that if anything it would work even better on a reread.

I’ll leave the last words with Kitty, a sentence spoken to Joe in a scene we visit repeatedly in the text, each time revealing a little more detail.

‘Life is only worth living because we hope it will get better and we’ll all get home safely.’

Nobody here is getting home safely.

Other reviews

I’d like here to point to John Self’s review for the Guardian, which he links to from his blog here, Trevor’s review at themookseandthegripes here, and savidgereads’ review here.

I mentioned above the neighbour, Madeleine. A thread here is her birthday, which everyone is ignoring. At various points she loses clumps of hair in drinks and food. I wondered if all of this was a Mrs Dalloway reference, but only The Independent seems to have picked that up, here. I’ve not yet read Mrs Dalloway so I’d be grateful for any comments on that front from tose better informed.

Filed under: Levy, Deborah Tagged: Deborah Levy