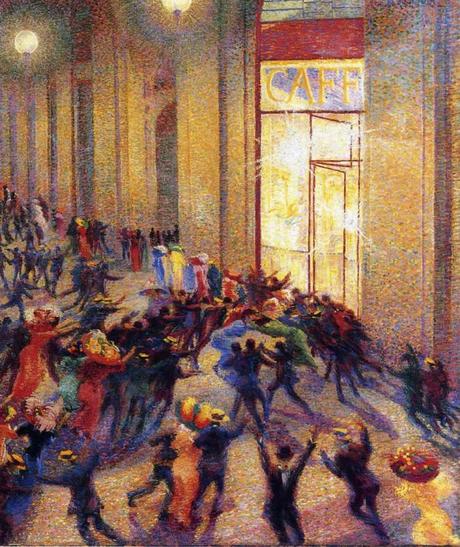

Umberto Boccioni, Rissa in galleria, 1910

In 1861 Italy becomes a united nation, and the myriad of small states in which the country had been divided comes together, not as one unity, but as a coherent system of suburbs. The Piedmontese monarchy lies over the country an elegant carpet, under which teems a world of desperate people—hungry, ignorant, violent people. The writers are the first to look under the carpet. Matilde Serao, in the footsteps of Eugène Sue, describes the stinking hubbub of Naples in the Belly of Naples (1884), a decaying city kept in darkness for centuries. Remigio Zena, in the Mouth of the Wolf (1892), depicts the alleys of Genoa, that port whose tall buildings cover a thriving, reckless humanity. In Milan rattles a furious yet cheerful mob, and the Happy Rogue(1885) is the title of a book by a romantic Milanese writer, Cletto Arrighi. It was him who invented the name for a group who, first in Milan and then in Piedmont and elsewhere, was scourging the literary scene: the Scapigliatura. The Scapigliati, literally ‘dishevelled’ or ‘unkempt’, are the Italian equivalent to the French bohème. Opposed to classicism, the prevailing pattern of literary academies, they didn’t just want to lift the carpet of good standards, they wanted to rip and tear it to pieces, pleased to show the horror that lurked underneath. Their name evokes messy hair and disregard of the rules of good manners: of a bourgeoisie satisfied by the services of impeccable tailors and barbers, sleek and idiotic in their collars, who will watch the collapse of the imperial Kakania in the pages of Robert Musil.

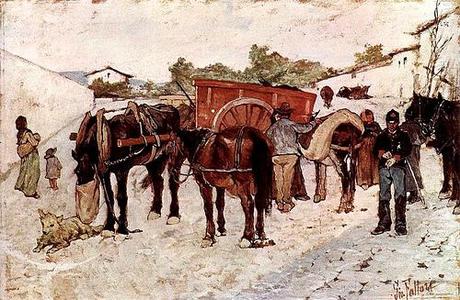

Antonio Conte’s hair was sparse and not well-combed, like those of some midfielders used to the dirty job. After regaining through a successful intervention a luxuriant head of smooth hair falling on his big blue eyes, Conte has returned to Juventus, the capital of Italian football, after several experiences in border towns. In the system of the ancient Italian states, Siena was caught between the influence of Florence and Rome, whereas Bergamo was the westernmost offspring of the Venetian state, already gravitating into the orbit of Milan. While in the province, Conte mastered a dishevelled type of football, an irreverent 4-2-4. It should be up to strong people to administer the borderlands, unruly by nature: an uprising in Bergamo, in fact, put an end to his government. A long satirical tradition considers the Sienese mad: mad enough to accept a blatantly offensive game. It is all different in the surly city of Bergamo, clustered between the subdued, pervasive Catholicism of the Po valley and a pseudo-Calvinist ethics of work—a city of cautious bourgeois whispering with their hands behind the back in inaccessible lounges and the people wrestling to win land from the mountains. Lorenzo Lotto’s 1524 fresco of St. Brigid, in the Suardi chapel of Trescore, near Bergamo, fits this division very well. The sumptuous robes of the donors, bowed in the shadow of the crucifix, are in front of our eyes but in a second floor, poor peasants exhausted from an old beast of a job to receive the offerings of the saint. I believe that Conte’s football could not adapt to this worn-out people: it was either too garish or too sophisticated.

At Juventus, which is probably the most prestigious academy or prominent institution of Italian football, Conte has announced the intention to comb his hair. He has applied his favorite tactical scheme with some hesitancy; so far, the team moves prudently: a rappel à l’ordre for the coach? As for the rest, Conte is proving to be quite different from his predecessors: hard and fierce in enforcing discipline on the field, with strict rules of conduct applying to all players. Another small yet revealing innovation involves the language. Juventus fans, recently, had become used to Luigi Delneri, whose vocabulary is made up of rough, unintelligible gibberish, and by a single adjective, ‘important’, relentlessly stuck to things, people and situations alike. This adjective is a cornerstone of the reified lexicon of middle class footballers, soccer academics, tories and whigs of the locker room. Against the term, there is only a sparse avant-garde. If Mourinho was a brilliant futurist of the newsroom, transforming interviews and press conferences into laboratories of impertinent stream-of-consciousness narrative and into happenings of deviously calculated misbehavior, Conte is dipping football in old and primordial images, discovering its true seed in the act of eating.

The 1880s and 1890s in Italy are as crucial for literature as for soccer: Pro Vercelli was born in 1892, Genoa in 1893, Juventus in 1897, this last from a merge between old teams like Football & Cricket Club Torino and Nobili Torino, which in turn gave birth to the Internazionale Torino. The greatest late-nineteenth-century Italian writer is, without a doubt, Giovanni Verga, the author of short stories and plays of timeless intensity. Biblical and Homeric, in his novels The Malavoglia (1881) and Mastro Don Gesualdo (1884) Verga manages to create an epic of the Sicilian people. The new Italy discovered through him a fierce Sicily: archaic, ill, eroded by an unbearable story that was crumbling down. Similarly, at the end of The Door, a masterpiece by the Hungarian writer Magda Szabó, the protagonist enters in the apartment of the mysterious Emerenc and discovers what was left behind: beautiful furniture by a cabinet maker of the eighteenth century. But when she opens the windows to contemplate and touch it, everything crumbles into impalpable dust. Worms and time had destroyed the remnant of an era, the ancien règime had disappeared. Verga’s novels are full of decrepit buildings that hide the waste of a nobility swept away by history. Struggling with it, there are folks who contend wealth and possessions with ferocious and inhuman devotion. Above them lies an inexorable fate that condemns to death—death by disease, consumption, idleness, impotence, folly or vice. This stuff of history, as Verga called it, la roba, marks this undistinguishable accumulation of fields, farms, money, houses, and goods.

The belly of Naples, The Mouth of the Wolf: Italian literature of the nineteenth century has a strong oral drive, a fixation on swallowing and digesting. In Verga, the verb ‘eat’ recurs obsessively. Diseases eat people; assets are eaten; a parvenu eats the possessions of a noble; working eats life. Before the match against Bologna, Conte explained that his team would literally have toeat grass. After the match against Siena, he also specified that if you go to play against certain provincial teams like Siena itself with the wrong attitude, they will eat you. Indeed, Conte said that Juventus would have to be ready to eat the field, or would otherwise be eaten by others. (He added that arrogance and presumption lead nowhere, a commonplace of football, or life, but also something reminiscent of the archaic anthropology revealed by Giovanni Verga.)

Conte is from Puglia. Like Verga’s characters, he comes from scorching, yellowish lands, where olive trees spread, the plains are fertile, and the cicadas at noon induce to sleep under the sun. You can succumb to the languid demon of midday, or you can crush it with work. Mastro Don Gesualdo has literally destroyed himself of work, a meticulous, obsessive, daily work; a job that is incomprehensible to the eyes of a community hostile to him and his fabulous wealth. A work, moreover, seen as a banner against the presumption and arrogance of a class of landowners drowned in idleness, convinced that they had received all rights with birth. Don Antonio the coach tests patterns, controls the diet and the sleep of his players, records each match, including the training games, and makes them reconsider their errors. We can imagine him on a mule with cotton trousers rolled to his knees, watching the irrigation of the fields; or else barefoot, controlling the pressing of the olives, and then milking goats, scolding the farmers and correcting the shepherds.

This is why one perceives something primordial in Conte, fierce and bloody. He’s not yet another hyper-coach, with a fetish for databases, happened by chance in a pioneering stadium. Conte is a primitive, an enriched Sicilian farmer of a hundred and fifty years ago. Without that belief that if you’re not eating first, or the other or the field, you will be eaten—not just defeated, but swallowed, digested, made to resemble an unrecognizable blurb in that monstrous womb of the homo homini lupus, the wolf’s mouth—Conte would not exist. Conte is a temporal suburb in a time of new and often rich geographical peripheries. All with the chromosomes of a feral culture, which eats or is eaten, where there is no mercy, no agreements, no solidarity.

Antonio Conte may, and perhaps wants to, transform the league into a duel to the death, in a fierce and bloody ritual. During the game against Siena, about to push Krasic into the mix, we have seen him shouting tactical instructions, and the surprised face of the Serbian was that of someone who did not understand anything. Many have thought of a language problem, but perhaps it would be truer to say that in that exchange of a few seconds there was a terrific anthropological meeting. Can a man from the Balkans really understand the world of Antonio Conte? Can a man who comes from a culture that is tragic but also noisy, grotesque, clownish, prone to hybrid sharing as to fierce hatred, understand the culture of eating and accumulating, its manic and exhausting work? Much of Conte’s charm is to be an avatar of Verga, a sediment of cultural layers, a deposit to be excavated to reach the geological origins of soccer, unexpectedly intertwined with the unity of Italy. ♦