Alessandro Del Piero and Luigi Buffon—modern heroes, chosen with pride over a pyramid of soccer spoils casting glances against the dark-green curtains of history—are sinking deeper and deeper into a gallery of noble moribunds, pale masks, plaster casts. They are dying. The clock that stood in the vestibule is either broken or made a home for mice. They may still uncover clever intrigues with an energy no one suspected them to have, cut off rebels’ heads while they can, but soon enough the God of Sunset, his language incomprehensible like a stepsister from the book of Joshua, will bring ash-colored clothes and bloodless hours of monotony, slowly deliberating: “Such is time, my dears, such and not otherwise.”

There are those who are trying to disinherit them (Storari almost won the trial). And there are those who try the even more obvious extravagance to play instead of them, only to be reminded that Juventus, like virtue, is not at all an asylum for the weak. (The art of renunciation is an act of courage—it requires the sacrifice of things universally desired for matters that are both great and unpleasant.) We don’t want to accept the reality of their technical death, yet we lack physical evidence and irrefutable proofs that they can both be made to speak with their own voice, like the Great Mute. We know that certain technical falsifications can be made, as when Del Piero’s knee cracked in Udine, for example, or when Buffon was seen cursing and smoking in the rain during the betting scandal, trying to defend the authenticity of everything he had done in his life, from wearing the 88 shirt to playing an entire season with the sciatic nerve hurting like being stabbed with a dagger.

We don’t want to accept it because we know that their handwriting on the original contract made in Turin—the word ‘v’ of ‘Juventus’ written like an open eight, a somewhat wavy, and then suddenly stopping movement of the pen—contained more than an intimate confession, it was a manifesto and a prophecy. (Indeed, it was as if Vermeer and Rembrandt had both signed in the register of Saint Luke’s Guild.) We don’t want to accept it because we have a great fear before a revelation, and withold of consent to a miracle. But will it really bring us relief if we substitute the word necessity for the word Providence?

In the eyes of their biographers, Del Piero and Buffon are craftsmen, so to speak, who work in the matter of illusion, rather than masters of truth. They always told splendid stories, and everyone gladly listened to them. They were the attraction of the place, like a big butterfly or an exotic animal from the court of the Chinese emperor Shi Huang-ti. If they had chosen, at some point, to hid in mountains and remote monasteries, their life of exiles would have been tracked by a pack of informers, seeking the secret of their eternal heart, the eternal liver, the eternal lungs.

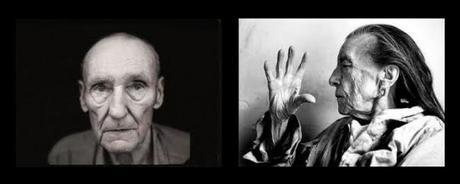

Rembrandt, Old Man in Military Costume (Los Angeles, Getty Museum)

Del Piero and Buffon, however, are not alike. The number 10 is a hunter of episodes by trade and instinct, cunning like Dutch baker van Buyten, who secured a hundred florins under the kitchen stool for the baptism of his male son. The number 1 is holding on his reputation as eccentric young man, as if he knew that those who were to exclusively concentrate on the precise architectures of his goalkeeping work, perfectly indifferent to material affairs, and liberated from all passions, would find certain technical mistakes that, so far, he had been able to mask under a youthful whim. With little practical sense, his thumbs are always up in hope that the absentminded spectators would not even notice—but it happened otherwise. Unmistakably, the captain is better than his friend at being an ideal wise figure. A man who grew up smelling radish roots before his daily walk in the farms of Veneto, Del Piero is roaming cold rooms of the Juventus palace with a foreboding that his role of adjunct-striker for the Old Lady will not be his last. He is so stately that when he plays, if he plays at all, he looks like a Seneca whose veins are about to opened by a slave (there is a painting of this by Rubens).

It is not true our entire soccer life appears in front of our eyes before death. That great recapitulation of existence is an invention of the poets. In fact we sink into chaos. Within Del Piero and Buffon there is a confusion of days and nights, they do not distinguish Sunday fixtures from Champions League memories, they confuse positions and passes. When a free kick is given, their breathing and their heart are silently praying to experience, once again, the grace of cosmic order. O holy ritual of everydayness, without you time on the pitch is empty like a falsified inventory that corresponds to no real object. If Del Piero and Buffon ever succeeded in combining a particularly intensive cobalt with a luminous, lemonlike yellow, their reflection in decline strikes the thickness of gray—a monument of fidelity with a triangular Juve-portal and two false windows where pitchy darkness lurks. ♦