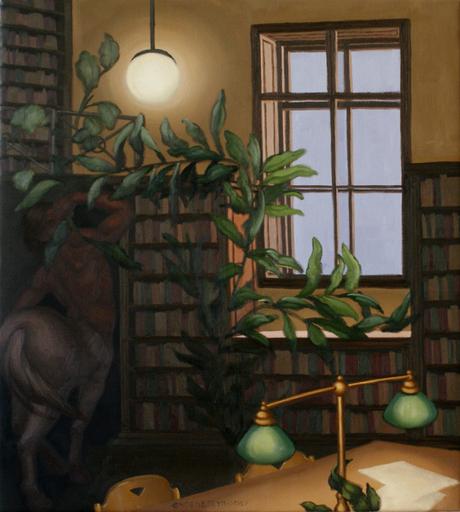

The struggle (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

There are few people who can both write about art and produce it. I have been cautioned against attempting the superhuman feat of doing both. Undoubtedly, there is a lot of impassioned but mutilated thought that has been scribbled down, and a lot of cleverly strung together ruminations that entirely miss the point of the artwork in question. Regrettably, frenzied vehemence and smooth yet detached theorising tend to be accepted as legitimate encounters between art and writing, as though art ought to infect words with its garbled passions, and as though crystalline categorisations really said the whole of what is to be said about art. An honest, steady, thoughtful middle ground is difficult to attain, but it is this gravity and lucidity that Susan Sontag manages to achieve in her essays on film, theater and literature. Against Interpretation and Other Essays thrusts us deep into the works in question, considering them, as it were, from the inside. Sontag is both artist and thinker: author and critic; able to love and to measure, to experience and to judge.

The essay. Perhaps, itself, a dying artform. It is easy to dash off an article, a commentary, a review, some quick thoughts, or a summary. But to engage with ideas–whether they emerge from books or paintings or elsewhere–involves something more. It involves a cohesive train of thought, an argument, an insight, a real willingness to enter a zone of intellectual conflict. In the case of writing about art, the essay is a knife, sharpened for the express purpose of permeating the flesh of the artwork to get at what is inside, to taste it, to judge it, to display its qualities for what they are. Perhaps things were ever as dire as they seem to be now: but writing about art, if at all penetrable, is so often vapid promotional cotton candy; sugary teasers that are little more than loosely-clad advertising, slick and professional, treading lightly so as not to crush any toes.

As for myself: Perhaps you have traced my artistic education, observing my first tentative steps into the world of painting, as I respectfully recounted it online. I kept my eyes open, I exposed myself to many things. I thought fiercely and critically about all of it–all of it–I agonised over the disappointments, the ineptitude, the obtuseness, the deception, the sheer ignorance. I think one does not improve unless one learns to discover faults, and can explain why they are faults, and propose ways of addressing them. As an artist, I kept these considerations to myself and applied them in practice. But in writing about art, I maintained a certain reverence. I made a conscious choice to be just, but positive: to focus on the best things.

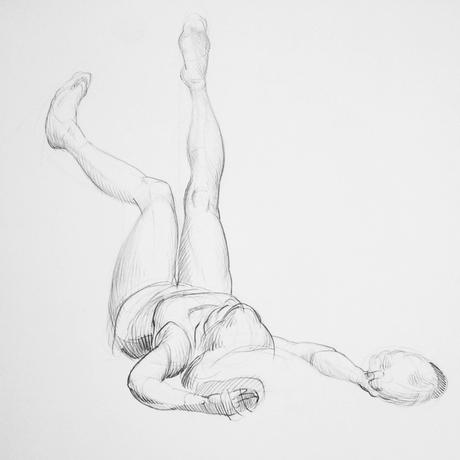

Copy after Klinger

A curious but probably predictable thing came from this: I was plagiarised. My thoughts found themselves rehashed, sloppily restitched and dimly cited in monstrous word-spaghetti that no longer conveyed the original idea, if any at all. I went to exhibitions where my own words were read back to me, translated into German. It made me consider who has these jobs, and why they don’t know what to say about art. Certainly, artists don’t always know how to write about their work, and that’s why they paint it. But if people who are otherwise proficient writers can’t produce a faithful and insightful piece on a work of art, the problem seems to be deeper. They cannot think about art. They stand before a painting in a distracted panic.

But not all of us do. Some of us approach an artwork attentively, quietly, patiently. We take our time with it, revisit it, think on it. Sontag (1966: 12) is not at all incorrect to say that ‘attention to form in art’ is urgently needed. The formal properties–how color is used, how strokes are applied, linear rhythms and the balance of shapes–might not be the entirety of a painting, but taking them in is surely the place to start. The little ripples of paint will soon chase away the anxiety, drawing us into a silent and timeless realm, inviting us to reflect. Our thoughts will scurry around with the worries and agitations that we hug to ourselves every waking minute, but these, too, will slow down. A painting is a shy creature, but approached through its form, it might let us near it.

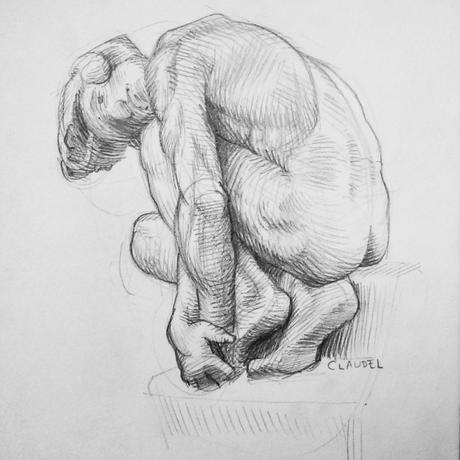

Copy after Claudel

Sontag’s essays, as a collection, make me consider the art I encounter and what is being said about it. I have known highly trained painters, self-taught painters, casual painters, designers, illustrators and conceptual artists across the world. Sontag looked fiercely at the world around her, she wrote about the time in which she lived, about America, about Europe. Her essays are not lighthearted, not necessarily short, not lazy Sunday supplements. They are the product of an active and alert mind wrestling with works that stimulate it or disappoint it and unleash a response. Goodwill is no vice, but the critic, the thinker, has work to do, and goodwill must not cloud the public discussion about art. We came to be impressed, to be stirred, to greet grand ideas–when art fails us, it is not we who should be ashamed, apologetically carrying home our embarrassment at the artist’s deficiency like a tail between our legs. Our critical faculties have not failed us. The art is rubbish.

Sontag (1966: 12) demands a kind of criticism that genuinely responds to art, rather than one that ‘usurp[s] its place.’ Words continue to threaten to replace the artwork, but the situation has grown considerably worse: the words are disposable, interchangeable, unilluminating and cheap. Barely able to capture a coherent thought, they could hardly hope to upstage an artwork. The real threat is whether such vacuous feel-good writing blinds us to art entirely, dulling our sensibilities, subduing our objections. The remedy has been around for some fifty years. We need:

‘Acts of criticism which would supply a really accurate, sharp, loving description of the appearance of a work of art. This seems even harder to do than formal analysis.’

(Sontag, 1966: 13)

The conjunction of sharp and loving is surprising but utterly natural. For how can one love a painting without discernment? How can one withhold affection from a painting that satisfies visually and stirs thoughts even in the silent mechanisms of its construction? Sontag (1966: 14) urges us to recover our senses, and that call is no less urgent now. Once we’ve learned to trust our senses, we must also remember to sharpen our judgements of what we perceive: to be fair, incisive and to demonstrate our love for thoughtful, well-crafted art.

Copy after Veronese

Sontag, Susan. 1966. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.