.

Poysdorf is just a border town with a considerable road traffic, as it lies on the main route between Viena and Brno (these four letters are not an abbreviation for Barcelona, but a Czech city called like that, Brno, silly as it sounds). As a compensation, the EU has granted it some candy: a little park and the pavement of the road. But if we manage to forget about the many vehicles crossing the town, it turns out to be a fine place.

I left Vienna in the morning, after my logistic stopover there, and decide on an overnight stay this side of the border (despite having ridden only 65 km this far) because I plan to cross tomorrow the Czech Republic in one go, not stopping for even a coffe. Nothing against the Czechs, but I don’t want to exchange money and try to get familiar with a new country just for staying one day.

The hotel I booked online in Poysdorf, Eisenhuthaus, pleases me since the very first moment: a refurbished house with big neat rooms, though not sumptuous, a luminous and quiet Mediterranean looking inner terrace or patio, and two nice and serviceable employees. As I have the whole afternoon ahead of me, I take a long stroll on the countryside, full of vineyards. This is a wine producing region of Austria, and there are two wineries in Poysdorf whose produce I’ll taste later.

Upon returning from my walk I come right across the town’s cemetery, and I fancy paying it a visit. I’m not a necrophiliac, but I like to step into a graveyard every now and then because it helps me to focus, to play things down, to take a perspective on life; it imbues me with some pleace, despite the emotional pain with which I always regard the idea of death. I find it useful -I hope- this memento mori, remember that we’re going to die and that all our ambitions and struggles, sacrifices and hopes, cares and joys, all our loves, friends, family, our goals, achievements and failures, the knowledge and wisdom treasured up along decades, the pain and the pleasure… remember that all that will be swallowed by the nothingness in a brief collapse, that last sigh after which not even the absurd of it all will remain, nor a recollection -in the long run- in anyone’s memory.

Humble iron cross in the graveyard by the church.

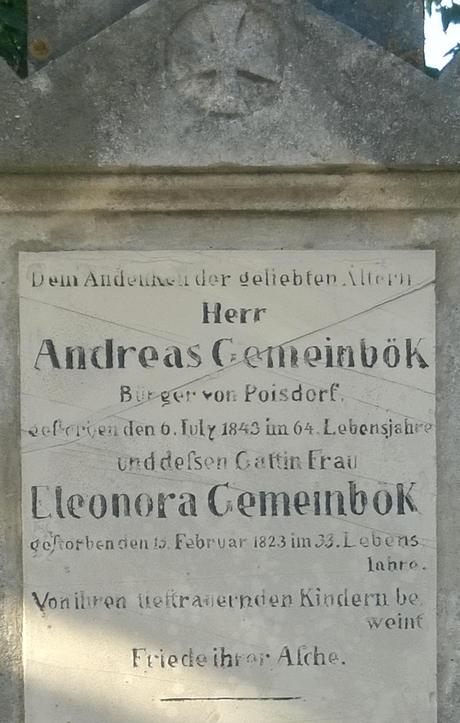

Memento mori. A gravestone in Poysdorf’s cemetery.

And now, after this somber moment, let’s toast to life: as we’re still here, and alive, let’s go for those Austrian wines! At the restaurant I order two of them, whites, dry and semi-dry, that I find quite fine. Not that I understand anything about wines; rather, I only know whether I like them or not; but I’ve certainly tried hundreds of them along half a century, and I must say these two from Poysdorf taste quite good. I take a note of this region.

Next day I get on Rosaura and, as I said, we cross the Czech Republic on one go. Right at the Austrian border my odometer indicates that I’ve already left behind, under the wheels of the motorcycle, four thousand kilometres in this journey to nowhere. Not knowing my destination, how many more are yet to come?

As soon as I arrive to Poland I feel at home. It’s not my first time here, of course. Poland is my adtopted land, a country that has seen me enjoy and suffer almost like any other, that has given me bliss and sorrow beyond measure. And it’s only after entering this time when I realize that, subconsciously, I had set it as my first aim this trip. On the other hand, it also “helps” to feel at home the fact that here, same as in Spain, they have a police State: back to the administrative surveying bureaucracy, the police cars on the streets (though fortunately not so much on the roads, like in Spain) and the ID control when registering at the hotels.

Poczta Polska, the Polish post service.

Only eight kilometres beyond the border I find a village called Międzylesie, and, in it, an outdated hotel called Zamek, which means castle, or palace in this case. Its decline captivates me at first sight, with those large halls and dark corridors, the old fashioned furniture, music from the 70′s, big bedrooms with high windows, all old wood. A very quiet place this is, more like a monastery than a hotel. My room overlooks the restaurant’s terrace on the vast inner yard, where a couple of women labour on DIY refurbishing works and two men burn a few boards on the grass. But their voices and the noise seem to come from very far, like if the air was thinner here and the sound traveled slower.

Hotel Zamek Miedzylesie.

The hotel is almost empty: during the three days I spend here — because I’m feeling so good — I cross no other customer except a couple my age and their daughter, a pretty young lady with a nice body that loiters in front of me just so I can watch her. And indeed I do, but out of the corner of my eye, not to feed her vanity.

In my first evening, while I’m exploring the village, I take only two photographs; and when I check them later I realize that, without meaning it, they hold a big part of the Polish social reality. Were I asked to summarize this country in just two photos, this might be the winning combination.

The first picture reflects the veneration this society has for the late pope John Paul II, beatified: there is hardly any locality in Poland where you can’t find, at the very minimum, one image or statue of him.

Poland venerates John Paul II.

The second image depicts a scene repeated ad nauseam on the streets and parks of this bittersweet country: a group of men drinking beer, on a defiant attitude, often shirtless and always, always uttering the same word: kurwa (whore, bitch), seemingly the only content of their conversations.

This I coined as kurwing around.

On the morning of the third day I pack my cases and say goodbye to the hotel. The couple and their daughter left yesterday, leaving an even deeper feeling of loneliness. And I go north, towards Wroclaw, and then beyond, towards the wearisome Polish plains.

.