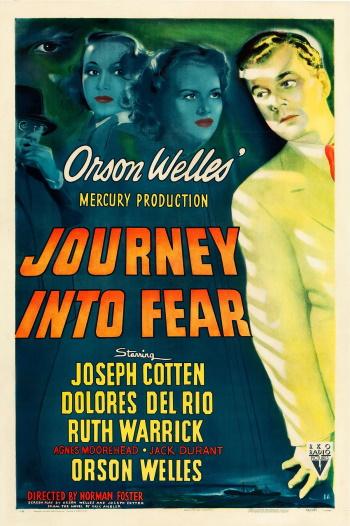

The book was filmed in 1943 – produced by Orson Welles, starring Joseph Cotten and Dolores del Rio. In the film, Graham is American and some of the plot has been altered.

Book review by Jane V: I enjoyed reading this book, despite my preconceived notions of not liking spy novels!

The situation is this:

The tale is set in 1940, during the period known as ‘the phoney war’, before WW2 had got seriously into gear. The story begins in Istanbul where our malgre-lui hero is found on a sensitive business trip to Turkey. He is a weapons engineer and has been sent by his company (Messrs Cator and Bliss Ltd) to draw up plans to rearm the Turkish navy. Turkey is a British ally. In the initial pages of the novel Graham is about to set sail on his way home is a tramp steamer which plies between Istanbul and Genoa. He has a gunshot wound to his hand, and has ‘learned the sense fear’; so we know that he is in danger. The story then back tracks to Graham’s arrival in Istanbul, at the end of a tiring business trip in mid-winter and after floods and an earthquake have made travel difficult. (The earthquake is a fact.)

The chief characters are:

Graham – his surname – a ‘brilliant engineer, though you would never think it to look at him’. An unassuming chap who is generous with his whiskey, married to Stephanie, a nice woman with whom he lives ‘in an atmosphere of good-natured affection and mutual tolerance’; he owns a nice house in the north of England. He is much traveled in his job and picks up languages easily. (Apparently Ambler also knew some Turkish)

Kopeikin, a Russian émigré, the company’s agent in Turkey. (Who takes Graham to Le Jockey Club, a night club. ‘Coloured saxophone players, green all-seeing eyes, Easter Island masks, and ash-blond hermaphrodites with long cigarette holders.’) While at the club Graham’s attention is drawn to a man who keeps looking at him. (‘a short thin man with a stupid face, very bony with large nostrils, prominent cheekbones and full lips pressed together as if he had sore gums or were trying to keep his temper. He was intensely pale and his small, deep-set eyes and thinning hair curly hair seemed in consequence darker than they were. The hair was plastered in streaks across his skull. He wore a crumpled brown suit with lumpy padded shoulders, a soft shirt with an almost invisible collar, and a new gray tie. A nasty piece of work then and definitely someone to be wary of.

There Kopeikin introduces Graham to Josette, a singer and dancer, and Jose, her ‘agent’. Josette can be hired for a price as a temporary mistress and is coming to the end of her employment at the club. Graham finds Josette attractive. ‘Graham was in the habit of comparing other women to his wife (Buxom good looks) as a method of disguising from himself the fact that other women still interested him.’

When Graham returns to his hotel room someone takes a shot at him, injuring his hand. The plot kicks off! Kropeikin arrives and insists that Graham must not travel to Paris by train, as planned, and that he allows himself to be taken to see Colonel Haki, head of the Turkish secret police, one of Ataturks’ men. A suave professional and Kropeikin’s boss. It appears that it is important to someone that the delivery of the plans to rearm the navy should not reach England. Graham has been instructed by his company not to commit his plans to paper so he carries his designs in his head. Haki reveals that a previous plot to kill Graham was foiled and it is suspected that a German agent named Moeller was behind it. Graham is shown some photos of possible suspects and identifies the man in the crumpled suit at the club. Haki says he is a professional gunman named Banat. A hit man. It is Haki’s job to get Graham home safely.

And so Graham finds himself booked on the tramp steamer to Genoa. This boat takes only a few passengers so his safety is thought to be secure.

The story then plays out in the close confines of the Sestri Levante.

The nine other characters onboard are:

M and Mme Mathis, a French couple returning home after M. Mathis has been working with the French railway company in Turkey. The wife is particularly shrewish.

Josette and Jose, who, it turns out is her husband.

Mr Kuvetli, a Turkish traveler in tobacco.

Herr Doktor Haller, who introduces himself as a ‘good German’ and an archaeologist investigating the early pre-Islamic cultures. He delivers lectures on this subject at every meal. And his wife who keeps mainly to their cabin.

An Italian woman, apparently in mourning, accompanied by her eighteen year old son.

So we have the perfect ‘Cluedo’ situation. Is one of these characters the assassin? When the hired gunman joins the boat in Piraeus Graham knows that his life is again in danger.

Finally, ashore in Genoa, the action really hots up and Graham must use all his courage and wits to remain alive. The crunch comes when, a prisoner in a car with four ‘baddies’ Graham escapes from this very tight corner with all the aplomb of James Bond – and none of the equipment.

I found this novel both well written and pacey. Characters are illustrated in short, vivid physical descriptions. Places are colourfully painted. Conversations between characters, particularly between Josette and Graham and Graham and Herr Haller air interesting political and cultural ideas. One passage which particularly interested me is when Graham holds in his hand the gun Kopeikin has given him. Even as a weapons designer Graham has never paused until now to think of the end result of his inventions:

For Graham a gun was a series of mathematical expressions resolved in such a way as to enable one man, by touching a button, to project an armor piercing shell so that it hit a target several miles away plumb in the middle. It was a piece of machinery no more and no less significant than a vacuum cleaner or a bacon slicer. It had no nationality and no loyalties. It was neither awe-inspiring nor symbolic of anything except the owner’s ability to use it. His interest in the men who had to fire the products of his skill as in the men who had to suffer their fire (and thank to his employers’ tireless internationalism, the same sets of men often had to do both) had always been detached. To him who knew what even one four-inch shell could accomplish in the way of destruction, it seemed that they should be – could only be – nerveless cyphers. That they were not was an evergreen source of astonishment to him. His attitude towards them was as uncomprehending as that of the stoker of a crematorium towards the solemnity of the grave.

This is possibly, I feel, a observation direct from Eric Ambler himself.