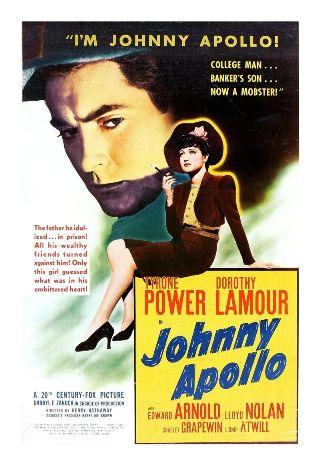

It seems that I’m drawn back, time and again, to what we can term transitional works, be they westerns or any other genre. I suppose that reflects my own interest in observing the general shape of cinematic development, and the progress of popular culture overall. The more hyperbolic aspects of marketing might like to encourage the perception that new styles or movements suddenly explode onto the scene without warning and forever change the face of entertainment. However, that’s not the case at all, and I doubt it ever will be. No, all things grow out of and build upon what came before, some in a more radical fashion than others. Film noir was the great game changer in Hollywood in the 1940s, and it’s evolution fits the trend I’ve mentioned here. The French critics of the post-war period may have noticed what looked to them like a dramatic new direction in cinema after years of being starved of new US movies. Still, that was just an altered perception resulting from a unique set of circumstances; film noir took form just as gradually as any other cinematic movement. Johnny Apollo (1940) is one of those movies that shows the transition happening, borrowing heavily from the socially aware gangster films of the 30s and blending in the makings of a darker, more fatalistic tone.

The film follows the ups and downs of Bob Cain Jr (Tyrone Power), a carefree member of the wealthy elite who sees his life take a dramatic downward turn. The opening is pure 30s, as a frenetic Stock Exchange suspends trading amid accusations that Cain Sr (Edward Arnold) is an embezzler. This fact, along with his father’s indictment and subsequent imprisonment, leaves the younger Cain in a spot. His privileged upbringing has left him unprepared for such a rapid downfall. His initial reaction is a combination of naivety and a kind of spoiled petulance – how could his father disgrace him and damage his social standing in such a way? At this point, we’re looking at a deeply unsympathetic character, and I think one issue with the film as a whole is the fact that this initial selfishness is never quite overcome. However, Cain Jr soon feels the chill wind of reality as his attempts to make his way in the world get scuppered again and again by his father’s new notoriety. It would appear that all those friends and contacts were all of the fair weather variety. In one curiously satisfying twist, Cain finds himself shown the door by a boss who finds his concealment of his identity particularly distasteful – his own old man having died a drunk in prison. So, with his options running out fast, Cain finds himself drawn into the shady underworld of Mickey Dwyer (Lloyd Nolan), a big-time gangster. It’s here that Cain undergoes a major transformation, adopting the pseudonym Johnny Apollo and using every illicit means at his disposal to rise through the ranks of the underworld, all in the hope of securing his father’s release from prison. Personally, my biggest problem with all this is the matter of plausibility. Gangster movies of the classic 30s period did see honest men drawn into a life of crime by a mixture of social pressure and a desire to strike it rich. The crucial difference though is that those 30s movies generally featured lower class guys whose choices were dictated by their poor backgrounds. Johnny Apollo asks the viewer to accept that such circumstances could lead the wealthy down a similar path. Frankly, I have a hard time buying into that idea, and although the incongruity does recede somewhat as the story moves along it’s difficult to shake it off completely.

Was Henry Hathaway one of the most versatile directors ever? Even a brief scan of his credits would suggest that he may well have been. Hathaway’s career was long, varied and successful, with examples of top class work in just about every genre. It seems that to be considered among the great director’s one needs to have either a recognizable motif, or to have concentrated in one particular genre. Hathaway was one of those thoroughgoing professionals whose dedication to his craft seemed to preclude any of the personal touches we associate with the more highly regarded figures in cinema. From a critical perspective, it was also his misfortune to be such an adaptable filmmaker – it’s much more difficult to put any kind of personal stamp on movies when the style varies so greatly. However, Hathaway remains one of my favorite directors, and I don’t think I’ve ever been completely disappointed by one of his movies. Johnny Apollo is well shot throughout, but the jailbreak finale is probably the real highlight and really ramps up the excitement. Unfortunately, from my point of view anyway, we get a coda tagged on which looks like it’s just there to provide a weak happy ending.

While I’ve admitted that I’m not altogether happy with the plausibility of the central character’s development, I can’t lay the blame for that at Tyrone Power’s feet. I feel he managed to nail the shift quite effectively – from fresh-faced enthusiasm to dismay, and finally a kind of ruthless single-mindedness. His interaction with Edward Arnold was well handled too, and this is crucial since the father son dynamic, and expectations of each, forms the basis of the story. Arnold had the more sympathetic part though; he may be an actor we don’t normally think of in such a light, but he brought a great deal of quiet dignity to his role as the fallen tycoon. However, as is often the case, Lloyd Nolan nearly steals the picture from under everyone’s noses. Nolan was a terrific actor, whose distinctive delivery and likeable demeanor, even when he was being vile, always adds something special to a film. In Johnny Apollo, Nolan was vicious, mean and hypocritical, but you can’t help rooting for him just a bit. I find it difficult to think of Dorothy Lamour without recalling her films with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. She’s good enough as Nolan’s put upon moll, and Power’s object of desire, but the Hope and Crosby connection makes her seem a little out of place in a straight drama like this. I’ll add a word of praise too for fine supporting turns from Lionel Atwill, Marc Lawrence and, most particularly, Charley Grapewin.

I’m pretty sure Johnny Apollo was only ever released on DVD in the US as part of a Tyrone Power box set from Fox. I never picked up that set since the other movies contained didn’t especially appeal to me. Instead I bought the movie when Bounty in Australia put it out as part of their noir line. The film is licensed from Fox and boasts a very strong transfer – it’s sharp, clean and has good contrast levels. The disc is a bare bones effort though with no extra features at all offered. Even though Bounty have marketed the film as noir, as I said in the introduction, this is very much a transitional picture. Frankly, the whole thing has more in common with 30s movies, but the seeds of noir are there too, with the last third delving deeper into the ambiguities of dark cinema. If the film is approached purely as a film noir then it’s likely to prove disappointing. Viewed as a kind of bridge in the evolution of the thriller, it’s altogether more satisfying.