Strange how it happens. Strange how an artist can have such a big impact in the U.K. yet barely transfer across the big pond to American audiences. Rory Gallagher was like that. Magnum was like that. Richard Thompson was like that.

And so was John Martyn. Although I'd heard his name for years, bandied about with names of other Brits I really didn't know like Daevid Allen, I'd never actually heard his music before. Or at least, didn't know that I had. So when this posthumous disc arrived at Ripple, I couldn't wait to drop it into the player and get myself educated. And if you're gonna bother to read this review, that's something you have to understand. This won't be a review written by a lifelong fan or someone who can compare Heaven and Earth to his hailed classics from the 1970's, like Solid Air. I'm not gonna be able to compare the texture of his voice to his last album, 2004's On the Cobbles. I don't know if this album is the best thing he's ever done or the most embarrassing. I've got no context to place these thoughts. What you're gonna get is my honest opinion of Heaven and Earth, with no preconceived notions of greatness or failure.

With that said, I love this album.

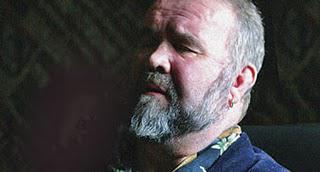

John Martyn first made his name rising from the same folk scene in London that spawned Al Stewart, Ralph McTell, and Bert Jansch. Slowly, he began incorporating elements of jazz, blues, and even reggae into his music and released his seminal albums in the early '70's. Around this time, his innovative use of the Echoplex, tape delay and recording techniques began to define his sound and he ventured off into ambient guitar textures, vocal intonations and a jazzy feel. Artists from Brian Eno to U2 to Bob Marley and Eric Clapton have hailed Martyn as a major influence. But just as talented as Martyn was, he also was troubled, erratic, and self-destructive with a lifelong battle with alcoholism. He lost his leg to septicemia/alcohol poisoning in 2003 and died a premature death in 2009 at the age of 60.

Heaven and Earth is the finished product of the final recording sessions Martyn was working on before he died, recorded in "every room" at Martyn's house on Woolengrange. Left with the series of tapes Martyn had left behind, his friends and confidants Garry Pollitt and Jim Tullio set about putting the pieces together as an album. Out of respect to Martyn, they left the tapes mostly untouched, exactly as John had recorded them, in their entirety -- even rambling at times. They then set about fleshing out the tracks, bringing in backing instruments and vocals by John's friends like Phil Collins. Throughout, they kept true to Martyn's distinct style for song creation, pacing, and flavor. So not so much an album, as a near stream of conscious creation of a man who'd been "dying" for years, but still felt the urge to create.

Heaven and Earth is the finished product of the final recording sessions Martyn was working on before he died, recorded in "every room" at Martyn's house on Woolengrange. Left with the series of tapes Martyn had left behind, his friends and confidants Garry Pollitt and Jim Tullio set about putting the pieces together as an album. Out of respect to Martyn, they left the tapes mostly untouched, exactly as John had recorded them, in their entirety -- even rambling at times. They then set about fleshing out the tracks, bringing in backing instruments and vocals by John's friends like Phil Collins. Throughout, they kept true to Martyn's distinct style for song creation, pacing, and flavor. So not so much an album, as a near stream of conscious creation of a man who'd been "dying" for years, but still felt the urge to create.Seen in that light, Heaven and Earth is remarkable.

From the first moment of opener "Heel of the Hunt," I was hooked. Right off the bat, I'm awash in the river of echoplex guitar that made Martyn famous. Not overwhelming though, it's subtle and near ambient but evocative. Then comes that first moment when I hear his voice. It's not a voice you'd not readily forget. Man, this is leather soaked in whiskey left out on a parched desert floor in the heat of summer. This is the voice of a man, weathered with age and disease, pulling notes from his vocal chords as if each tone could extent his life by another moment. Yeah, I'm reading far too much into this knowing that he died recording this album, but maybe I'm not. Listening to this, it's the sound of a man who knows his time is coming soon. Soul burns through the gruffness of his vocal chords, hoarse and deep, and full of all the cumulative pain a man can experience in 60 years of harsh living.

As a comparison, I pulled up a video of Martyn singing "May You Never," off his big album, 1973's Solid Air. Man, it's not even close. Each alcoholic moment, each heartbreak, each painful memory is now etched into that voice. It's become so deep, so thickened, so raw over the years. He knew. He knew he was dying.

Some won't like that voice. Some will compare it to early times. I won't. I have no comparison. All I have is that voice. A voice so knowledged and aged. It's amazing, and I wouldn't trade it for the world.

But it's not just the voice, it's how it works with Martyn's sparse but undulating arrangements that adds to it's power. And never is this more soul-shivering apparent than on "Heel of the Hunt." Against teardrops of tape-delayed guitar, amid the gentle percolation of a muted Reggae beat and undulating bass we hear John reaching deep into his soul, "Please don't abuse me/please don't abuse me/ah please excuse me/come on, just use me/but don't make me laugh." Backing vocals from Phil Collins jump in, "Be at peace now/be at peace now," he sings. "Don't make me laugh" John counters. "Be at peace now, child." Phil replies. The effect stirs my skin. Rivers of goosebumps bleed through my flesh as my imagination runs wild to a fictional image of the weary and worn warrior kneeling in prayer with his six-string to give his final confession. His wounds too harsh to endure. His frailty too much to overcome. A final cleansing of his heart to his God as he looks towards a happier place that awaits him. A place where his long lost love will be waiting. Intense.

That tone pervades the album, even as some songs grow lighter and others darker. "Heaven and Earth," with it's jazzy piano chords reminds me of latter day Van Morrison, with that life-weary voice laying it all on the line through his barely discernible mumblings of lyrics. Almost fugue-like, again I see a dying man losing himself in a moment of near blissful catharsis, lilting from side to side, his eyes unfocused, seeing his lost love. "I would move heaven and earth/just to be with you/yes, I would move heaven and earth/just to be by your side." It reminds me of Don Quixote moanfully singing "Dulcinea" to his imaginary love as he died at her feet in Man From La Mancha..

"Bad Company," in style, tone, and pacing recalls "Low Spark of High Heeled Boys," by Traffic. Here, Martyn finds a sandpaper-y upper register to his leather-worn voice and it's perfect. Life gets injected through his vocals. Caught somewhere between blues and funk, "Bad Company" smoulders with a sultry knowing. "Could've Told You Before I Met You," is a slice of glorious jazz pop with Martyn's gargled vocal seeming to reach for moments of optimism and hope. "Can't Turn Back the Years," is a tender, sorrowful look back at a life filled with mistakes and regrets played over a languid jazzy beat. Martyn's voice sounding even more weary and threadbare here, if that's even possible. "Willing to Work" closes the album with a dynamite, guitar-effect laden slow burn of resolute stubbornness. Lost within the gospel inflected backing vocals is Martyn's declaration that he's not quite done yet. That he won't go quietly into the night.

But he does.

The album certainly isn't perfect. Some of the tapes did wander on too long. "Stand Amazed," at 6:50 of female gospel vocal and jazzy New Orleans flair could've used a little editing, but I respect their decision not to. And overall, many of the songs are rather spartan, coming across as fleshed out sketches rather than fully realized compositions. It's all a bit ragged. But that's OK. it's all OK.

I don't know how this stacks up as a John Martyn album. But I do know how it stacks up as a snapshot of honesty, pain, and reflection. The overall tone is languid, but it's not a downer. In fact, it's strangely uplifting, as if John's last confession can help free all of us from the mistakes we're about to make.

"I could of given you everything you needed Martyn sings with a snag in his throat, " but I can't turn back the years."

It's a remarkable album

--Racer

Buy here: Heaven & Earth