First edition cover.

First edition cover.

Book Review by George S: Jim Redlake is a long novel (787 pages), telling the story of a young man's journey to adulthood. Jim is the child of a fractured marriage; his father is a dreadful novelist who is unfaithful to his wife and wants to let his new woman take charge of Jim. Jim's mother rebels, and takes Jim away to her parents, a country doctor and his snobbish wife. They accept the boy, but Jim's mother is sent away, because marital separation means scandal. The book follows Jim through meetings with the local aristocracy on the hunting field; education at Winchester, and then at medical school; farming in South Africa, and fighting in German East Africa in the First World War. The book is very long, the values are conventional, and the plot depends on a fair number of coincidences, but I enjoyed it thoroughly.

For a start, Francis Brett Young has the qualities of a genuine novelist. His characters are mostly far enough from standard types to have some interest and complexity. Jim's grandfather, a country doctor, comes alive through his small acts of kindness that make him his patients' friend as much as their doctor; his grandmother, on the other hand, who begins as merely an unfeeling snob, gradually unravels and becomes a figure of dangerous irrationality. He's good at observation, of details of costume, for instance. He's also good at smells. There is the down-at-heel parsonage, with its odour of 'stone-flagged passages, bread and butter, and lavatories' and the medical school, which smells of 'stale vitiated air, air pungent with chlorine or sleepy with alcohol, air made nauseous by the sickly emanation of pickled humanity.' (Mind you, there are limits to what he notices; in the chapters set in Africa, the actual Africans are pretty well invisible.) He's good at analysing snobbery. There's a description of a garden party at a grand house, with all sorts of snobberies and pretensions laid out for our inspection. This chapter reminded me of Trollope, and the book is in many ways more like a Victorian novel than a twentieth-century one - and not just in its length. Inheritances and wills play a part in the plot, and there's the familiar trope of the hero at his lowest, walking away from his difficulties through bad weather, to find himself at the house of a long-lost relative. The classic instance of this is in Jane Eyre, but it's in other Victorian novels, too. Jim Redlake is Victorian too in being the sort of novel that Henry James disparagingly called a 'loose baggy monster', with all kinds of deviations from the basic plot, especially the long sequence about fighting in German East Africa.

I think its length and variety would have been appreciated by Brett Young's target audience. Some contemporary reviewers routinely commented that his books were too long (but then long novels mean that book reviewers have to do more work for their money) but length would be an appeal to the sort of reader who likes to wallow in a book for a long time - like the twenty-first century equivalent who likes to work their way through an entire box-set.

The war section is very good at conveying the hardships and frustrations of the African campaign, which is one rarely touched on in fiction. Brett Young had In 1917 Brett Young had published Marching on Tanga, a rich and exciting account of the action. (So exciting that in 1940 Penguin mistakenly republished this memoir in their fiction list - but in 1941 a new edition re-categorised it under 'Travel and Adventure'.) In Jim Redlake, Brett Young conveys the same enthusiasm for the men who fought in the gruelling campaign, and for Smuts, their General. He dissociates himself from the fashion in anti-war literature that had followed the publication of All Quiet on the Western Front in the late twenties:

In later years [...] a spate of war literature, as men called it, drenched the world, when the neurotic conscripts of all nations vied with each other in venting their tortured brains of the filth and fear and brutality which were all they remembered of war.

The Kalaharis, says Brett Young, have a spirit which, 'without any romantic self-hypnotism or sentimentality' could acknowledge the 'filth and fear and brutality' but 'put them in their proper place.' On the other hand, he does allow himself criticisms of the Army's organisation that he had not put into marching on Tanga. He does this mostly through the words of the medical officer Martock, who is clearly something of a self-portrait, and who rages at the inefficiencies of all organisational matters having to go through the bureaucracy at Nairobi hundreds of miles away.

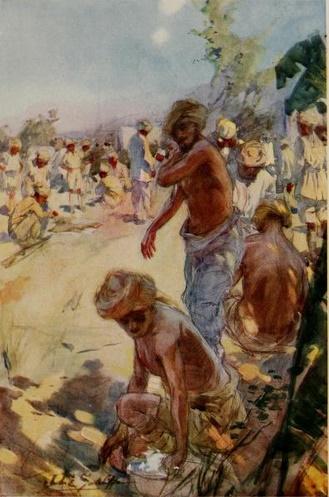

'Sepoys bathing' : an illustration from tht first edition of Marching on Tanga (1917)

'Sepoys bathing' : an illustration from tht first edition of Marching on Tanga (1917)

Another aspect of the novel that appealed to me was its inclusion of various novelists among the characters, in what amounts to a considered manifesto on what a novel should be and what it should not be. The first novelist we meet is Jim's father, George Redlake, who epitomises all that a novelist should not be. He is flashy, and has a high opinion of himself:

By the time he was twenty-five he had found himself adopted by a small and, as he thought, esoteric group of grim intellectuals whose flatteries turned his head.

His books create mild controversy by dealing with shocking themes, but he goes in and out of fashion. When he tries to appeal to a wider public, they see that his work is insincere, and it fails. He is an unrooted man, constantly moving from one part of the country to another. His novels tackle fashionable 'issues', and Brett Young editorialises that he should have stuck to writing essays; 'he was too much interested in abstractions, too little in humanity ever to have made a novelist.'

In other words, he's Brett Young's demonstration of how not to be a novelist.

In striking contrast to George Redlake is Starling, a working-class novelist who comes to live in Jim's London boarding-house. Starling is a man of great energy, defiantly working-class, self-conscious and touchy. He has a ferocious personality and his 'sunken eyes smouldered fiercely as coals': His brow was massive, and cleft, at the root of a flattened pugnacious nose, by a zed-shaped wrinkle like a deep incision [....] Jim might have taken him for a motor-mechanic who did a little boxing 'on the side', till he looked at his hands, which were small, white and delicately-shaped, though long-nailed and stained at the finger-tips with two kinds of ink. When Jim meets him he is working on a novel is 'about as different from your father's as you can imagine,' The people in it are 'concerned with essentials; he tells Jim:

'They're alive - I tell you they must, they must be alive, if I put the last drop of my blood, the last breath of my spirit into them. Not living corpses. Alive!'

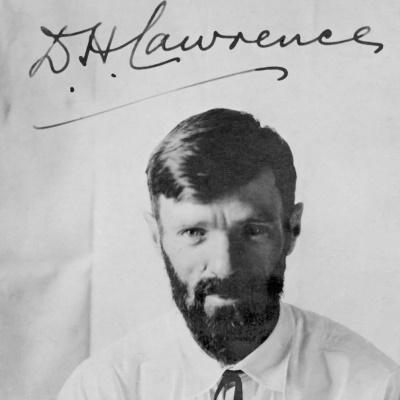

This is the vitalist rhetoric that is characteristic of D.H. Lawrence, whom Brett Young knew in Capri after the war. The identification with Lawrence is made more certain when he remarks to Jim:

'England, my England! as soon as this cursed war's over I'm going to clear out of it.' ( England, my England is the title of Lawrence's short story collection.)

Starling, we are often told in the course of the book, is 'the real thing'.

Lawrence died early in 1930 and Jim Redlake was published towards the end of the year. There would just about have been time for Brett Young to have written the Starling chapters as a tribute after Lawrence's death. Maybe significantly, by the end of the war, Starling is no longer a novelist, but a poet. Is this a comment on Lawrence, whose post-war novels became less rooted in social actuality, and more apocalyptic?

Another novelist appears later in the book. He is Martock, who is, like Brett Young, a medical officer with the troops in East Africa. Martock's 'principal care was his battered portable typewriter, from which nothing but death should part him',on which he is writing a novel about the Black Country and the Welsh Marches. The Iron Age. He 'types away' even when being transported towards the fighting zone 'inside the iron oven of a sun-blistered cattle truck.' This is clearly Brett Young's self-portrait in miniature slipped into the book. The book he is writing sounds very like Brett Young's The Iron Age (1916) We are not given any hints about the quality of Martock's novel, but he is clearly different from George Redlake, in that he is a rooted writer, writing about the places he knows and loves even when far away.

There is one final novelist in the book. When an adolescent, Jim Redlake's ambition had been to be a poet, but he is discouraged from this, and his writing (rather bad sonnets of unrequited love) dries up when he gets involved in hard work in Africa. At the end of the book, though, having experienced much, and grown up during his wartime experiences, he announces:

'I am thinking now, that now, at last, I shall write a book.'

'About the war?' his wife asks.

'Lord, no. I can't say. About swallows if you like, and - I don't know - life in general; how astoundingly rich it is, in spite of everything.'

That description fits Jim Redlake rather well. The novel will be emotion recollected in tranquility. It will also be the fruit of his lived experience, and will be sincere. Not quite like Lawrence's novels perhaps, but a good recipe for middlebrow success.