that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

It says in the Talmud that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

Throughout history, a number of places have been venerated for their holiness: the Ganges and its passage through Benares in India, the Valley Of The Kings in Egypt or the tomb of the poet Hajez in Iran. They are all realities. Nobody is denying this. But Jerusalem poses myriad questions. Was it the Garden of Eden? Was it the cornerstone on which the Arc of the Covenant would be built? According to Hebrew legend, the temple was erected on the exact spot where the waters of the Great Flood sprang. The rock was called Ebhen Shetiyyah, the Foundation Stone, and the first solid body in Creation as God separated the Earth from the primitive bodies of water. It may have been here where King David watched Bethsheba as she bathed, which led to him marrying her. David's mortal works and personal failings left God with no choice but to instruct him to not build the temple himself but leave the task to Solomon, his son with Bethsheba. In the Book of Chronicles, David confesses: “God told me: You will not build a house in my name because you are a man of war." The Wailing Wall, where Jews still pray to this day, is believed to have formed part of the temple wall.

Jewish Cemetery, as seen from the Kidron Valley

Awaiting The Redemption

The future can be guessed at by looking down on the city from the top of Kidron Valley or Josafat where the 3,000 year-old and largest Jewish cemetery in the world stretches out below. There is precious little space left among the 150,000 tombstones for new burials. For this reason, the last remaining outer rows have long been bought up, at unimaginable prices, by grand Jewish banking families now living in Manhattan. They want to be assured of their future place for the day when, according to the prophets, God will initiate the Redemption there. All are buried with their feet towards Temple Mount, in identical 120cm plots. On Judgement Day, God must find them all facing the right way.

Kidron Valley spreads beneath the cemetery and seperates the city from the three hills to the west of Mount Scopus, seat of Hebrew University, the Mount of Olives and Mount Scandal. Inside its walls, commissioned by King Soloman the Magnificent of his arquitect Mimar Sinan, the same architect who festooned Istambul with its most beautiful mosques, the Old Town is divided into four sections: Armenian, Jewish, Christian and Muslim. Four separate worlds sharing the same sun and the same God. Each one of them smells different - cardamom coffee, hookah tobacco, sweet breads, dried lamb's blood. From the Damascus Gate, one can see women laying out spinach leaves on rags in the street; flags with the Star of David (Palestinian never, they're banned); young girls selling peaches and cherries from wooden carts; monks calling the faithful to prayer at the nearby Al-Aqsa mosque; young women wearing veils; nuns in blue and white habits, priests in black, Orthodox Jews in kaftans and black hats, Israeli soldiers with their UZI rifles cocked, stray dogs. And rubbish. A lot of rubbish. Shells exploding, ambulances wailing, remnants of barbed wire.

The rest of the Old Town encompasses a constellation of holy places. Stringent visiting restrictions at the two most significant non-Jewish monuments, namely the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre, were introduced in 2017, perhaps in anticipation of the tension about to escalate around them.

Restoration work

At the time of writing (January 2018), King Abdullah of Jordan is on a visit to the Vatican. He calls the Pope “My dear friend and brother” and gifts him a painting representing Rome, the Eternal City. The Hashemite dynasty are custodians of Jerusalem's holy Muslim sites. Also happening around this time is the culmination of seven years' restoration work on the 1,525 square metres of mosaics at the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa mosque. Out on the esplanade, Jordanian and Palestinian restorers worked away in silence, at a time when rage was making its comeback. The restored mosaics, which decorate the walls and vault of this famous octagonal building, consist of over 2 million coloured glass tiles with gold, silver and mother-of-pearl. Contained within the gilt ones, in their crystal soul, is a fine layer of real gold.

The Dome of the Rock is the oldest Muslim building in the world. It guards the stone of Mohammed who, because of his affinity with the Jewish faith, also held Jerusalem as the Holy City. According to a tradition heavily steeped in poetry, Mohammed received here the first of his revelations from the Angel Gabriel, who told him he was to be Allah's messenger. Years later, Gabriel was to appear again, bringing the white horse, Buraq, which carried Mohammed at lightening speed to a sacred rock on the top of Mount Moriah. This was a key place in Hebraic faith for being the stone upon which Abraham offered his son Isaac to God as a sacrifice. From there, Mohammed ascended a staircase of bright light to the Seventh Heaven where he was proclaimed superior to the Old Testament prophets. This journey to heaven is remembered in Sura 17 of the Koran entitled: "The Children of Israel". When Caliph Omar arrived in Jerusalem in 638 AD CE, six years after Mohammed's death, he built a wooden mosque that would later become Al-Aqsa. Mohammed's heirs established their capital in Damascus and decided to make Jerusalem a place of pilgrimage as important as Mecca and Medina. They confided in Byzantine, Greek and Egyptian architects to build a stone cupola for over the sacred rock of Mount Moria; an octagon with with twelve interior columns and four piers supporting the golden hemisphere. These were the sacred shapes and numbers of Eastern religions. The smaller Al-Aqsa mosque, at the extreme southern end of the platform, was given a silver dome and gold and silver doors. These two sanctified structures were to become magnets for the faithful.

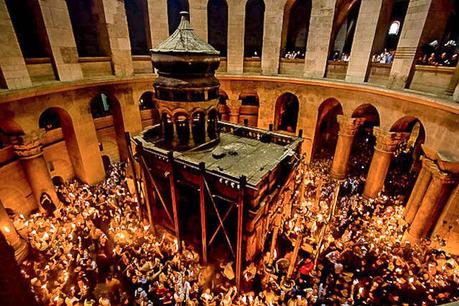

Interior of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Renovation of the Holy Sepulchre, which was completed in March 2018, freed the edicule from its corset of iron girders, a scaffolding that had constricted it since 1934. It can now be seen exactly as it was conceived in 1810. A team, led by the Athenian Antonia Moropolou, are unanimous in describing the most exciting moment of the nine months the restoration work lasted, as the removal of the marble cladding protecting the rock bench where Christian tradition believes the body of Jesus Christ lay. Through a tiny door in the Chapel of the Angel, antechamber to the tomb, a glass panel covers the marble slab, leaving the original rock of the tomb inside exposed.

The "Day of Rage”, December 2017. Streets of Ramallah.

The "Day of Rage"

The front pages of newspapers across the world went with various different analyses of the same photograph. A young man hurls a stone with his sling as a battle rages on around him. These were the streets of Ramallah on the "Day of Rage", so named by Hamas in order to fire up Palestinians against Trump's decision, the previous December 6th, to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and his decision to move the US embassy there from Tel Aviv. The young man in the photo has his face covered by the keffiyeh of a new intifada and his gesture is one of hate. He's the present-day Discobolus, a discus thrower of the Instagram era. The expansive curve of his stone throw is already turning into a spiral of violence. Neither side wants to lose their children again.

Seventy years ago, the United Nations agreed a plan to partition Palestine, which had been under British mandate since the end of the First World War. A little over half the territory was assigned to the Jewish state, as proclaimed officially in May of 1948, and the remainder was envisioned for a future Arab state. Jerusalem would be accorded corpus separatum status, a separate entity under international jurisdiction. But the war waged between the Jewish forces and Arab countries, until the armistice of July 1949 was signed, put paid to the UN's plans. The west of the city was occupied by Israel, establishing its capital there, and the east remained under Jordanian jurisdiction, as well as the West Bank. The Green Line of ceasefire dividing the city with barbed wire and barricades lasted until Israel's victory in the Six Day War of 1967. Since then, even her closest allies have maintained their embassies at a distance of 70 km.

Jerusalem is simultaneously glory and sin. Many are the writers who have left their mark on the palimpsest that is Jerusalem. From the 16th century travel guides, now decorating the display cases of the National Library in its Urbs Beata Hierusalem exhibition, to the words of Chateaubriand; "I stood, staring at Jerusalem, measuring the heights of its walls, memories from history all the while coming to me ..... Even if I lived to be a thousand years, never could I forget this desert that seems still to breathe the greatness of Jehovah and the terrors of death".

Measures of sorrow

However, claims The Economist, that aforementioned distribution of measures of beauty (yofi) from the Talmud might at times seem erroneous. And what if it were instead measures of sorrow that God gave the world? Nine for Jerusalem and one for the rest?

There are two instances of this in the city today. Yad Vashem is one of the most impressive museums in the world. Its objects, photographs and videos underline Man's capacity for creating destruction among his counterparts. One is Jerusalem's Holocaust Museum, 180 square metres of passageways and galleries charting the history of the extermination of six million Jews during WWII. Located on the Hill Of Remembrance, Yad Vashem was founded in 1953 by an act of the Israeli parliament. Moshe Safdie's building is astounding. A triangular prism seen to penetrate one side of the mountain and come out the other. The visual sensation is unique: a base in almost darkness but a sky lightly illuminated. Physical death but also spiritual life. "And to them will I give in my house and within my walls a memorial (Yad) and a name (Shem) that will never be cut off." Isaiah 56:5. Yad Vashem won the Prince of Asturias Award for Concord in 2007.

Yad Vashem Museum

A few metres away, and as if a continuation of the message, is Hadassah Hospital housing the world's largest skin bank. It has existed since the days of the years-long Second Intifada when the casualty figures screamed nearly a hundred suicide bombers, 5,000 dead and tens of thousands wounded, many of them burns victims. Here are kept, frozen in liquid nitrogen, 170 square metres of human skin, which is enough to treat about 100 people with 50% burns to their body. Jerusalem is all divisory lines, Vias Dolorosas, border posts and walls ~ much like Doris Salcedo's Shibboleth, a 546 foot-long crack in the cement floor of the Tate Modern, its 'scar' still visible today.

And its writers

Finally, Jerusalem today is also its writers. Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, books such as To The End Of The Land and real lived experiences, too. The eulogy that David Grossman read out at the funeral for his son Uri, 21, killed in combat by friendly fire in August 2006 when his jeep got hit by a Hezbollah missile, explains one way of living with a kind of severe serenity when surrounded by a sea of enemies. "For three days, every thought began with: "He/we won't". He won't come, we won't talk, we won't laugh ... Israel will have its own reckoning ... and we will act against the gravity of grief."

View from inside Yad Vashem Museum

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin