Today’s blog topic is a hangover from last year, when I had the idea of delving into detective novels featuring real historical figures. I had a search around and came up with a few possibilities but only got as far as one blog post. Until now, that is. I have been having a further delve into this type of fan fiction and come up with a few more historical figures to think of as fearless detectives.

After previously riding along with Ron Goulart’s Groucho Marx on his cross-country crime solving, I have taken a trip back into Georgian England to encounter writer Jane Austen (1775-1817) in hitherto unsuspected detective mode. Austen has obviously struck a chord with some crime writers, as I have come across no less than four attempts to portray her as an amateur detective. In addition, I have discovered that she is apparently something of a time traveler too. There may be more crime, or indeed, time traveling Austen adventures out there that I have not yet discovered. Here are the crime novels that I have found so far:

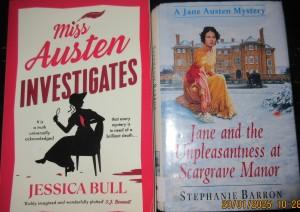

An Austen crime series by Stephanie Barron, an American writer, originally from New York. The series began with Jane and the Unpleasantness at Scargave Manor (1996) and runs to ten books.

Miss Austen Investigates by London born and bred writer Jessica Bull (Michael Joseph, 2024). This is the first in a new series, the second novel being The Hapless Milliner.

Jane Austen Investigations: Death of a Lady by Laura Martin, Sapere Books, 2023. This is the first in a series of five novels by the Cambridgeshire based author.

Jane Austen Investigates: The Abbey Mystery by Julia Golding (for younger readers).

I have dipped into the Austen criminal world with the above-mentioned Stephanie Barron novel and the first of the Jessica Bull novels. Each author depicts Jane at a different stage in her life, Jessica Bull choosing to begin her series in 1795. Here is a youthful Jane, a writer but not yet a published author. She is engaged in a flirtation with Tom Lefroy and hoping that he will propose. As Austen aficionados will know, the desired proposal does not materialise due to family intervention. This Austen persona is lively and feisty, though an infuriatingly immature twenty-year-old. Given that she would be certainly be considered to be at a marriageable age in that era, the characterisation grates somewhat. Actually, the Austen characterisation reminds me of Georgette Heyer’s lively fresh-out-of-the-schoolroom misses who embark on risky escapades at the drop of a hat, but in this case with less charm.

In contrast Barron chose to place her version of Jane Austen in a slightly later period of her life, 1802 to be precise. However, in common with Jessica Bull’s novel, Austen’s romantic life is not going well. She has just accepted and subsequently refused a proposal from wealthy landowner Harris Bigg-Wither on the basis that she did not love him. The story therefore sees Austen on a visit to a newly married friend, the Countess of Scargrave to escape the fallout and find some peace. Unfortunately, she ends up having to deal with the murder of her friend’s husband.

Stephanie Barron introduced her story using the well-worn device of the discovery of long-lost manuscripts and letters that just happened to be penned by you know who (a distant ancestress of some friends). These papers detailed Austen’s experiences with several detective cases and had been preserved for posterity and then forgotten. As we know, Cassandra destroyed much of her sister’s correspondence, so the conceit of the papers being found in an American descendant’s cellar neatly avoids having to explain why they were not destroyed. The book’s preamble has Barron being allowed to read the manuscripts fresh from the hands of conservators and against the background of anxious bidding from august literary institutions for the previously unknown Austen trove. It is a clunky beginning but the story is readable and the Austen persona more likeable than in my other sample of the genre.

Even after having now read a couple of books featuring a version of Austen as a detective, I am still baffled as to why anyone ever hit upon the idea. Perhaps it was simply the unlikeliness of the idea of a gently bred, clergyman’s daughter as a detective. Though come to think of it, that could almost be the fictional Miss Jane Marple, in more modern times. I have tried to work out why the idea of Jane Austen as an intrepid detective does not really work for me and I am still no nearer an answer. Perhaps it is because her real-life literary output, unlike say, Elizabeth MacKintosh (AKA Josephine Tey) has nothing to do with crime so that I am unable to take the idea seriously. Oddly enough, even though the Groucho book was playing the comedic persona to the hilt, the idea of him as a detective seemed plausible enough, as was the idea that he was aquainted with mobsters. Though according to a 2024 Guardian article it was Groucho’s brother Zeppo who was connected with various mobsters and the underworld.

That is only skimming the surface of the considerable amount of Jane Austen focussed crime novels. I may come back to this crowded field again at some point. And reconsider the appeal of Jane as detective perhaps.