The n-word has a status wholly unique in our language. There are many offensive words whose shock value has been worn to almost nothing. But the n-word stands alone as one you must never utter, or even write in full — not even in discussing its offensiveness. If you’re white. Though Black people use it quite ubiquitously.

You’d think one rule for whites and another for Blacks constitutes racial discrimination. Or they’re just messing with our heads. I find Black use of the n-word offensive in making a mockery of the whole matter. And frankly it seems ridiculous to hold the word unsayable while its abbreviated form, with exactly the same meaning, is okay.

The word is of course a corruption of “Negro” (which connoted skin color) and became, centuries ago, derogatory. But only in the 1990s did absolute prohibition take hold. Though researching this, googling “The n-word,” I was surprised to see Wikipedia’s article headed with the word spelled out. I myself am too squeamish for that.

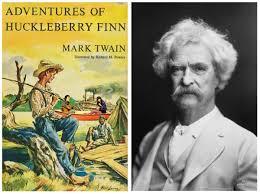

But meantime, so inflexible did the prohibition become that it led to the widespread banning of arguably American literature’s premier landmark — Mark Twain’s 1884 novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Which frequently contains the n-word, mainly regarding the character Jim, a slave. Yet what Twain was doing in that book was to humanize Jim, and by extension all Black people. To show they’re not (“n-words”).

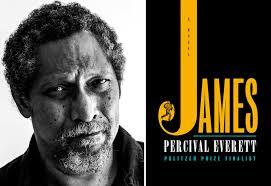

Comes now Percival Everett’s 2024 novel James. With Twain’s Jim as narrator. The name’s two versions are signifiers of relative dignity. The book’s last word is, indeed, “James.”

Also appearing throughout is the n-word. Everett is Black. I daresay no publisher would have touched this book if written by a white.

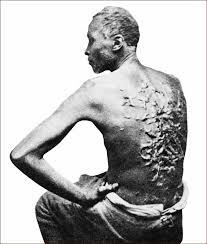

James is a searing, visceral portrayal of slavery. What it felt like being its victims. No Florida nonsense about its having somehow been a blessing for them. I was not previously naive on that score, having read (and reviewed) Edward Baptist’s unflinching book on slavery Both there and in Everett’s, whipping is not an incidental detail, but integral. Used constantly by white owners, terrified of their slaves, to keep the latter in terror too. James gets whipped and the reader isn’t spared. The “good, kind” masters are those who whip a little less horrifically.

James gets his for letting slip just slightly the mask slaves are supposed to show as marks of submission. The discordance between that mask and his reality is a constant in the novel. James is in fact very smart, learned, and well-spoken. He craves reading the likes of Voltaire and Locke. At one point his interior monolog invokes Kierkegaard. (That may have been overdoing it, Mr. Everett.)

But none of the Blacks in the book is portrayed as a stereotypical “darkie” (though some have so adapted themselves to slavery they actually seem comfortable in it). I’ve long believed American Blacks not inferior (per white racist notions) but in fact superior. Certainly compared to whites holding such stupid ideas. Blacks had to have become superior, by natural selection, because the challenges and rigors of slavery would have weeded out the less fit from their gene pool.

A wonderful early scene has James literally teaching a class of youngsters how to “speak slave.” Standard English being their actual native tongue, they must specially learn the “I’se gwine wif youse, sho nuff, Massa suh” language expected of them. Hearing anything else makes white heads explode.

This novel does not retell the Huck Finn story from James’s perspective. While it starts out that way, sort of, it soon diverges. Separated from Huck for most of it, James has his own travails, centered upon his quest to reunite with his wife and daughter. Complicated when he learns they’ve been sold away — to a plantation whose product is more slaves.

The end-game is very fast-moving, thrilling, death-defying. What James gets up to is perhaps barely credible. But Everett manages to bring it off.

I do note one mistake. The book is set in 1860-61.* It occasionally mentions nickels, but none were minted before 1866.

You might say the horrors of slavery depicted were all in the past; abolished several lifetimes ago. But its reverberations linger. As Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

* Twain’s a couple decades earlier.